Nancy Tuchman, dean of the School of Environmental Sustainability at Loyola University Chicago, speaks on how Jesuit universities can elevate education and action around environmental justice during the Commitment to Justice in Jesuit Higher Education conference on June 24. (NCR screenshot)

As the global community seeks solutions to climate change and other environmental threats, Jesuit colleges must lead by example and provide education aimed at creating a more just and sustainable world, a dean at Loyola University Chicago said at a recent Jesuit conference.

Nancy Tuchman, dean of Loyola Chicago's School of Environmental Sustainability, said directives from Pope Francis and the Society of Jesus on caring for God's creation make it critical that Jesuit schools put those principles in practice on their campuses and in their curricula. That includes joining the Vatican's new ecological action initiative and making environmental sustainability a core class for all students, she added.

"We're being called by so many of our Jesuit and Catholic leaders to really step up as Jesuit universities and take this on and move it into action," Tuchman said.

Students must be literate about the environmental crises facing the world, she said. "It's a disservice to humanity, it's a disservice to society for us to be graduating students that never heard about climate change through their four years of higher ed, and worse yet if they graduate being a climate denier."

Tuchman spoke June 24 during the final plenary session of the Commitment to Justice in Jesuit Higher Education conference, hosted virtually this year by Georgetown University during several days in June.

The conference was the sixth since 2000, when then-Superior General Fr. Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, in a speech at Santa Clara University, challenged Jesuit universities to integrate "service of faith and the promotion of justice" into their academic missions. The 2021 iteration, which coincided with the 500th anniversary of the conversion of Jesuit founder St. Ignatius of Loyola, was the first to include environmental justice on its agenda.

Calling environmental degradation "the existential, grand challenge of the 21st century," Tuchman said it is also a justice issue because of the disproportionate impact of pollution, droughts, flooding and other environmental threats on people who are poor or marginalized, future generations and nonhuman species.

Already, climate change displaces tens of millions of people annually — a figure that is expected to balloon by midcentury. Mining and deforestation have further forced Indigenous people from their ancestral lands, often leaving the land poisoned with toxic chemicals. In urban areas, pollution from landfills and hazardous waste sites is more likely to be located near communities of color.

'If we are not able to protect our planet, if we're not able to get off of fossil fuels and we keep driving climate change, the Earth will become uninhabitable for all of its forms of life, including humans.'

—Nancy Tuchman, Loyola University Chicago

And while some countries continue to consume natural resources at unsustainable rates, it's only because many people live in poverty that the planet has yet to blow past its limits, Tuchman said. Some studies suggest that as many as five Earths would be required to sustain the U.S. standard of living for everyone on the planet.

The connections between environmental degradation and poverty have been a key theme for Francis throughout his papacy, particularly in his 2015 encyclical, "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home." In that teaching document, he asked all people "to hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor."

In 2019, the Society of Jesus adopted four universal apostolic preferences, among them caring for our common home. In opening remarks at this year's conference, on June 8, Fr. Arturo Sosa, Jesuit superior general, said those preferences "are not priorities that pit one sort of apostolic work against another," but interrelated actions that work together like fingers on a hand.

"They are attitudes that must characterize each and every Jesuit work," he said.

Advertisement

Sosa said that in the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic — which he compared to the cannonball that struck St. Ignatius of Loyola during a battle in 1521 and triggered his personal conversion — it will be young people who "construct a new narrative of hope," and Jesuit schools can offer them the tools "for opening up a new path."

The superior general said the apostolic preferences provide a roadmap for a more just society that "recognizes the fragility of the planet, that fights to end the squandering of resources, the depletion of our forests, oceans and lakes, and that better cares for all our natural resources, with the goal of leaving a better environment to those who will follow us."

In the U.S., Jesuit schools like Loyola Chicago, Santa Clara and Seattle University are in the vanguard of environmental action among Catholic institutions, and numerous Catholic colleges have taken steps to shrink their carbon footprints, divest from fossil fuels and expand education on the environment and Laudato Si'.

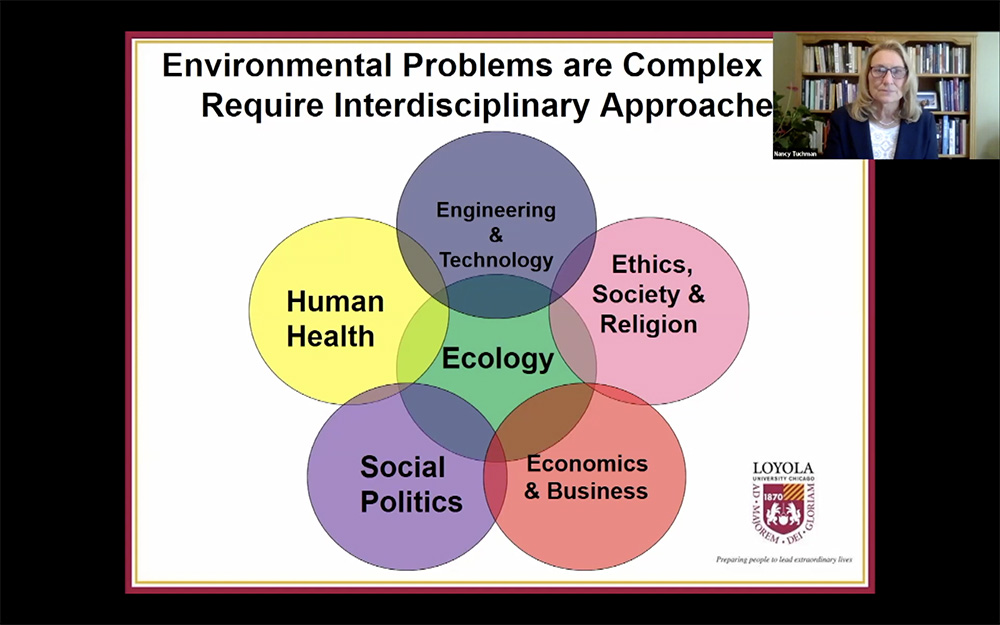

"We are never going to come up with environmental solutions if we're just thinking about it through the lens of science or the science of ecology," said Nancy Tuchman, dean of the School of Environmental Sustainability at Loyola University Chicago, during the Commitment to Justice in Jesuit Higher Education conference on June 24. (NCR screenshot)

Tuchman pointed out that surveys of incoming freshmen at Loyola Chicago have regularly shown that its commitment to the environment is an important factor in their choosing the school. An international survey by Amnesty International in 2019 found climate change was the top issue for Generation Z, along with pollution and the loss of natural resources.

Tuchman, a biologist who specializes in aquatic ecology, said Jesuit universities cannot leave issues of climate change and environmental degradation only to the sciences. She urged schools to integrate them across all disciplines and make environmental sustainability part of the core curriculum for all students.

"We are never going to come up with environmental solutions if we're just thinking about it through the lens of science or the science of ecology," she said.

The fields of engineering, human health, political science, ethics, religion and business all have roles to play in developing just environmental solutions, Tuchman said.

In particular, she recommended that Jesuit business schools lead a paradigm shift away from the mainstream, linear business model based on infinite growth toward a circular and regenerative model that makes better use of the planet's limited resources.

"This infinite growth model is based on a planet that is finite in its resources, so it is not sustainable," she said. "And what we're effectively doing today is stealing the future, selling it in the present and we're calling it gross domestic product."

Along with education, Tuchman said campuses must also put sustainability into practice. She encouraged all Jesuit schools to join the Laudato Si' Action Platform, which the Vatican introduced in May to encourage all sectors of the Catholic Church to work toward seven sets of sustainability goals in the spirit of Francis' encyclical.

The largest geothermal energy system in the Chicago region heats and cools the School of Environmental Sustainability at Loyola University Chicago. The system is one of the many ways the school is incorporating sustainable practices to lower its carbon footprint. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

"It's really a call for us to incorporate environmental sustainability into the mission of the university, the strategic plans of our organizations and certainly into the curriculum and into campus operations," said Tuchman, who provided a brief preview of the section of the platform aimed at universities, which Loyola Chicago is helping to develop.

The dean said that in Laudato Si', Francis spoke of the importance of environmental education in facilitating an ecological ethic that helps people grow in solidarity with the Earth and responsibility for caring for it. That need has never been more urgent, Tuchman said.

"If we are not able to protect our planet, if we're not able to get off of fossil fuels and we keep driving climate change, the Earth will become uninhabitable for all of its forms of life, including humans," she said. "And so this is really an enormous problem that we have absolutely got to tackle."