St. Thomas Aquinas, depicted in a 15th-century Italian fresco: "Aquinas did not begin with abstract principles or values, but rather began 'from the ground up,' generalizing from what he observed." (Wikimedia Commons/Silvio sorcini)

Jesuit Fr. Mark Massa opens his new book, The Structure of Theological Revolutions: How the Fight Over Birth Control Transformed American Catholicism, with a quote from Oliver Wendell Holmes' poem "The Deacon's Masterpiece: Or the Wonderful 'One-Hoss Shay': A Logical Story" first published in 1858. The preacher's carriage "was built in such a logical way / It ran a hundred years to a day" but then "went to pieces all at once, / All at once and nothing first, / Just as bubbles do when they burst."

The poem is, of course, a metaphor, and the destruction of the one-horse carriage Holmes is describing represents the sudden destruction of Calvinism as the essential cultural framework for New England society. After the antebellum division of "First Parish" churches into Congregationalist or Unitarian congregations, and the loss of orthodoxy at Harvard, New Englanders awoke to the realization they were now Yankees and no longer Puritans.

Pope Paul VI at the Vatican on June 29, 1968 (CNS)

"The American Catholic community experienced a very similar, and seemingly equally quick, disappearance of a revered theological system after 1968," Massa writes. "What passed from the scene was, as in the earlier case, a rigorously systematic, even logical, theological system, which has been traditionally labeled 'neo-scholastic natural law.' "

Massa notes we can pinpoint the destruction of the neo-scholastic shay with precision: July 25, 1968, the day Pope Paul VI issued Humanae Vitae.

Massa explains that this volume sets out to answer two questions: "How does theology — the study of God, whose nature is imagined to be eternal and unchanging — change over time? And why?" In searching for answers, he turns to Thomas Kuhn's seminal The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, from which Massa borrows the structure of his own title, and specifically the concept of paradigm shifts.

"Kuhn argued that science doesn't evolve in anything like a continuous manner, in which each development builds neatly on what has come before — a presupposition that most people hold when they use the word progress," Massa writes (emphasis in original).

Applying this insight to theology, and specifically to the "micro-tradition" of natural law thinking, Massa makes the case that "the history of theology has been marked by a regular series of ruptures, rejections, and reinventions, in which newer models are offered to replace the older ones, the latter no longer understandable in light of the new insights and data."

After a deep dive into the Kuhn volume, Massa turns his attention to four post-Humanae Vitae theologians, all of whom considered themselves to be working within the natural law tradition, and all of whom not only rejected the neo-scholastic thought that had informed the encyclical but whose new paradigms were radically different one from another, even while each drew on the tradition of Thomas Aquinas in one way or another.

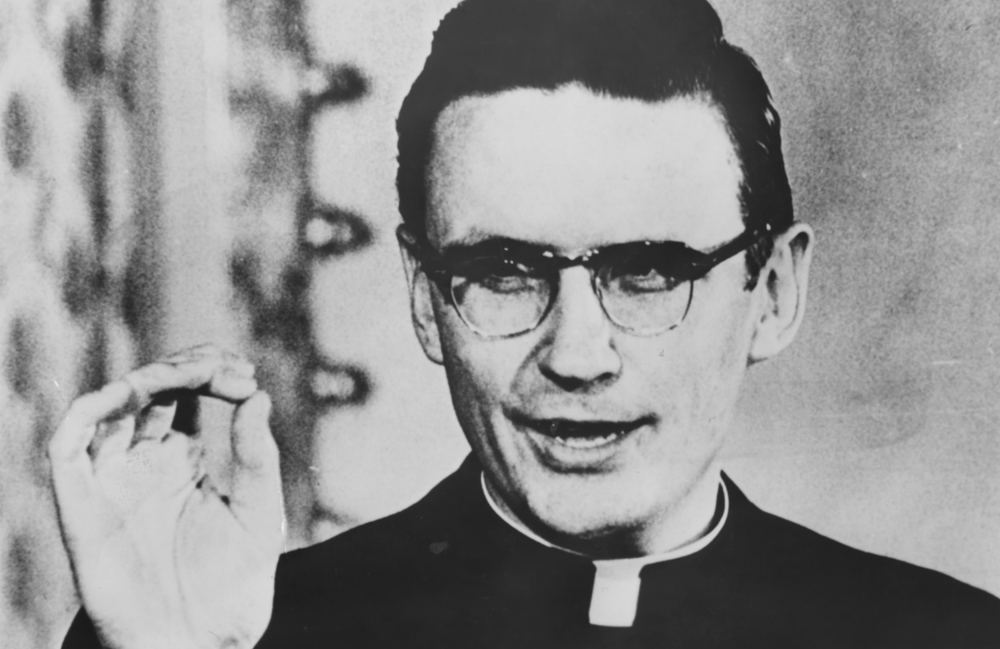

The first theologian examined is Fr. Charles Curran, who was teaching at the Catholic University of America when Humanae Vitae was promulgated. He quickly assembled a group of theologians to question the arguments contained in the encyclical — which took some doing in the days before the internet — and, on July 30, 1968, held a press conference at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, D.C., at which a statement signed by 87 theologians was shared with the public. The core indictment was that the encyclical rested on an "inadequate" natural law approach.

"The most basic presuppositions of the older [neo-scholastic] paradigm — that one could identify moral meanings in physical acts; that the Church was obliged to teach authoritatively in light of those physical acts; that the ultimate purpose of human coitus was openness to the propagation of the species — all of these were now determined to be not only unnuanced or overargued but also rather 'erroneous,' " Massa writes (emphasis in original).

Massa characterizes the challenge posed by Curran and his colleagues thusly: "The older paradigm didn't need 'tweeking' [sic] or refitting: it needed to be replaced."

At a press conference in Washington, D.C., on July 30, 1968, Fr. Charles Curran reads a statement signed by 87 theologians challenging Pope Paul VI's encyclical Humanae Vitae. (RNS)

Massa's treatment of Curran's challenge displays his comprehensive historical and theological knowledge, and incisive ability to locate the key points at issue in intellectual debates, and to do so with a certain empathy for positions with which he disagrees. For example, he writes:

The things that had made the neo-scholastic paradigm so attractive to some moral theologians since at least the 18th century — its "classicist" understanding of natural law as static, propositional, and timeless, which offered an ease of utility in laying it out and passing it on; it's [sic] ahistorical character, which made it applicable to all cultural situations and moral actors, making it seem universal and above cultural differences; its legalistic understanding of an eternal law as a source of obligations and restraint, which seemed to offer clear and certain propositions to often-difficult and messy ethical situations — we now declared to be fatal flaws that were profoundly inadequate, "or even erroneous." And the Catholic theologians who had signed the text ... pointed out that there were now other, less static and nonpropositional understandings of natural that "come to different conclusions on this very question [of contraception]."

This was not an "evolution," not a linear development of doctrine, but the replacement of one paradigm with another. And, in the event, while it was the singular neo-scholastic paradigm that was being replaced, there were multiple competitors seeking to replace it. Curran adhered to the natural law theories of Josef Fuchs and Bernhard Häring that rehabilitated the role of conscience in moral decision-making and found ways to creatively absorb and integrate knowledge drawn from human experience and, specifically, from advances in the natural sciences.

The second development in natural law thinking that Massa examines is the "new natural law" and specifically the work of Germain Grisez, who taught moral theology for many years at Mount St. Mary's seminary in Emmitsburg, Maryland.

Unlike his colleagues on the left, Grisez agreed with the conclusion drawn by Paul VI in Humanae Vitae that artificial birth control violated the natural law. But as Massa writes, Grisez "— like his colleagues 'on the left' — saw the profound intellectual incoherence of attempting to derive the 'ought' from the 'is.' " For Grisez, "moral norms — that is, guidelines for ethical living — had to be 'objective' in the sense that they were immediately apparent as 'goods in themselves,' with no need for speculative or metaphysical arguments as to why or how they were desirable." Grisez further argued that this was how Aquinas had understood natural law, and that Aquinas had been misunderstood by those who claimed him as their own.

Advertisement

The "new natural law," which was also embraced and nuanced by John Finnis, the Oxford philosopher who brought these theories to elite academic circles and shaped a generation of conservative scholars, was also known as "basic goods theory," in that it posited the existence of goods so basic to human flourishing that "taken together, [they] tell us what human persons are capable of being, not only as individuals but as a community." As Massa explains:

Four of the basic goods were what Grisez termed "reflexive" — that is, reflecting what kind of person one was: self-integration, authenticity, friendship and justice. Three of the basic goods he labeled as "substantive" — defining the substance of human life: life and bodily well-being, knowledge of truth and the appreciation of beauty, and "skillful performance" and play. The eighth and last basic good he labeled "marriage and family." As the new natural law adumbrated the foundation of moral living, individuals could never morally act against any of these goods, which would be irrational precisely because to act against them would be to willingly undercut one's ability to achieve full human flourishing, and would also stymie efforts to achieve communal flourishing.

Unlike the neo-scholastics, who appealed to disembodied, abstract human reason, Grisez appealed to human experience in his defense of Humanae Vitae. Contraception was not wrong because it contradicted some abstract teleological end of marriage. It was wrong because procreation is a basic good required for human flourishing.

Jean Porter, like Grisez, rejected neo-scholasticism for its abstract and unbelievable claims to moral certainty based on syllogisms. But she thought Grisez stopped short in recognizing the necessary embodiment of moral decision-making. She argued, in Massa's summation, that "all ideas — both ours and those of Aquinas — are imbedded in the stream of history, and thus need to be approached as historical artifacts shaped by intellectual and cultural presuppositions about which we are sometimes conscious, but often not" (emphasis in original).

Her historicist recovery of Aquinas, then, began with the recognition that "one of the most common mistakes made in retrieving medieval texts written about natural law has been a 'widespread assumption that they understood such key concepts as reason and nature in the same way as we do.' " I do not know if Porter ever met Justice Antonin Scalia or his originalist progeny, but she might have been able to teach them a thing or two.

Massa points out that perhaps the most important misreading of medieval texts that Porter recognized needed correction was the mistaken assumption that reason and nature were at odds, or at least in contrast, that nature was "pre-rational." She writes, "Grisez and Finnis share in the modern view that nature, understood in terms of whatever is pre- or non-rational, stands in contrast to reason. ... [But] no scholastic would interpret reason in such a way as to drive a wedge between the pre-rational aspects of our nature [on the one hand] and reason [on the other]. They always presuppose an essential continuity between what is natural and what is rational, since on their view nature is itself an intelligible expression of divine reason."

Porter attended to the particular and historic, arguing that "the concept of nature is, at least in part, a social construction," that "one does not 'observe' nature; one constructs it" (emphases in original).

As you can imagine, Porter was charged with being a relativist, but it is impossible to ignore the fact that all of our human claims and arguments are, beyond doubt, made within history. Divine revelation may exist as an eternal reality, but our understanding of it, like our understanding of nature, is something we partially create, not something we passively receive.

The final theologian Massa considers is his Boston College colleague Lisa Sowle Cahill. One of the leading lights among feminist theologians, Cahill appreciated Porter's concern for the culturally and historically specific, but she did not want to abandon the possibility of achieving a universal ethic. As Massa poses the question: "Can the concept of the 'common good' survive globalization?" Are certain practices, such a female circumcision, always and everywhere an assault on human dignity and, if so, how to ground such a universal claim in light of Porter's critique?

The key paradigm shift that Cahill introduced was to argue that if you are seeking a global ethic, you need not go fishing in the land of abstractions. You can go talk to ethicists around the globe and see if they can reach a consensus on key ethical questions.

"Over against the stark alternatives of objectivist foundationalism and relativist nonfoundationalism, one possibility is a refigured model of rationality that encompasses radical contextuality as well as cross-contextual, interdisciplinary conversation," Cahill explains.

Massa continues the explanation: "Unlike Kantian approaches to natural law like that of the new natural law, Aquinas did not begin with abstract principles or values, but rather began 'from the ground up,' generalizing from what he observed regarding human desires, behavior and social institutions" (emphasis in original). It was not just feminists who took a pragmatic approach to ethical foundations. It was Aquinas himself.

Jesuit Fr. Mark Massa, author of The Structure of Theological Revolutions: How the Fight Over Birth Control Transformed American Catholicism (Boston College/John Gillooly)

I have only summarized the arguments, which are much more complicated and rich in Massa's text, especially his closing analogies between his argument and the exegetical work of Scripture scholar John Meier, which almost take your breath away. His didactic touch is evident: Nothing is unclear as he makes his case with almost lawyerly precision that theology does not develop one step at a time, in a linear fashion, but with large and even sudden shifts of meaning.

In an age characterized by incivility, and in an academy that often rivals the sandbox as an arena for name-calling, it is refreshing to read an author who is so generous with different various points of view and the people who espouse them. Indeed, if I have a criticism of the book, it is that Massa employs the adjective "brilliant" so frequently.

At a time when so many Catholics yearn for a certainty that the Master never promised and that the tradition does not yield, Massa's book is invaluable in its insistence that change is not the enemy of theological truth but its companion. The neo-Feeneyites at First Things and in certain pulpits must ask themselves if they have answers to the questions to which Massa has offered, in my estimation, decisive, not to say ultimate, answers and observations. The ultimate is always beyond the horizon. That is part of what makes us human.

Intellectual breadth, empathy and precision, so rarely found together, and so illustrative of the best of humankind, are here combined into a tour de force. Anyone who wishes to be serious about the Catholic intellectual life must henceforth have a well-dog-eared copy of this book on their shelves.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest: Sign up to receive free newsletters and we'll notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.