CONSEQUENCE: A MEMOIR

CONSEQUENCE: A MEMOIR

By Eric Fair

Published by Henry Holt and Co., 256 pages, $26

Eric Fair has been a soldier, a police officer, a heart transplant recipient, a Presbyterian seminarian, and a torturer of his fellow humans. His memoir, Consequence, deals with his time as a perpetrator of torture in Iraq.

From his earliest days as a church youth group member, Fair burned with a desire to serve in the American establishment. After college, he applies to be a police officer. The police tell him he'd be a great applicant if he had military experience. So he enlists in the army. His aptitude for foreign languages sends him to the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, Calif., where he learns Arabic. This practically random assignment — to language school, and to Arabic — determines his future.

Before Sept. 11, 2001, he is honorably discharged from the Army and soon marries and becomes a police officer in his hometown of Bethlehem, Pa. It was in an attempt to join the Drug Enforcement Administration that a physical produced the statement one never wants to hear from a physician: "I've never seen that before." Fair had an idiopathic heart condition. His days as a police officer were over.

With law enforcement and the military closed to him, yet still eager to serve in some capacity, Fair finds the huge corps of companies providing "contractors" to the Iraq War effort.

In a harrowing series of passages in his memoir, Fair details the lax hiring processes and training for people who are tasked with interrogating captured Iraqis. A contact says, "They'd hire you in a heartbeat."

There was no interview, no medical exam, no background investigation for a high-paying job in Iraq in 2004 after a perfunctory training session of some 10 days.

Soon enough, Fair finds himself in plywood rooms near Baghdad, interrogating detainees. Says Fair, "I cannot ask God to accompany me into the interrogation booth."

What Fair realizes, and details in his memoir, is that neither he nor anyone else has much of an idea about how to interrogate anyone. He hears about master German World War II interrogator Hanns Scharff, who formed friendships with his American captives. After the war, Scharff became a United States citizen, was hosted by his former prisoners, and taught the United States military about interrogation. His technique was to befriend prisoners and take them out from the prisons for friendly walks in the woods.

But soon Fair is manhandling detainees who frustrate him.

Fair details his experience in his spare memoir, Consequence, adapted from an article he published in The Atlantic. Written entirely in the present tense, Consequence conveys Fair's bewilderment, his fumbling through life, his fight to retain his principles.

At the same time, the reader may wonder if he doth protest too much. He was not involved in the Abu Ghraib abuses, nor was he among those prosecuted for his work. His conduct was minimal compared to those horrific incidents. He witnesses worse conduct than his own, briefly, and is guilt-ridden over his failure to report it. In other publications, before his Atlantic article, he minimizes his conduct. He now says those reports were, at least in part, false. But even now, the extent of his bad behavior amounts to pulling chairs out from underneath young boys and shoving an old man into a wall.

But Fair shows sympathy for those treated worse by other interrogators. He provides some food for detainees. He lets a victim of sleep deprivation — not his detainee — sleep.

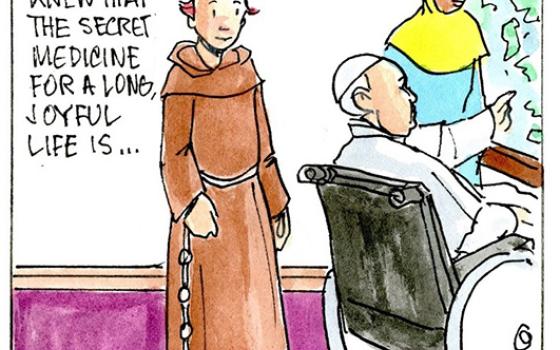

For the Christian reader, Consequence provides some thoughtful reading. Fair points out that the God of Scripture often works in prisons, but never on the side of the jailer, always on the side of the prisoner. Fair cannot find himself believing that forgiveness is a gift from God. Instead, "the memories of Iraq make believing that impossible. I need to earn my way back." Consequence is one step Fair takes to pay for that way.

[Robert Little is a lawyer in Southern California. NCR's book reviews can be found at NCRonline.org/books.]