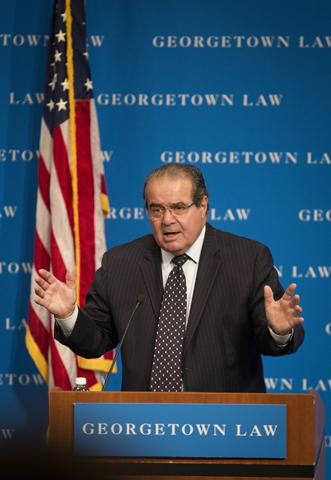

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia speaks at Georgetown University Law Center in Washington Sept. 30, 2013. (CNS/Nancy Phelan Wiechec)

SCALIA: A COURT OF ONE

SCALIA: A COURT OF ONE

By Bruce Allen Murphy

Published by Simon & Schuster, $35

For a generation, Antonin Scalia has served on the U.S. Supreme Court as a singularly polarizing figure. And yet even now, 28 years after he joined the court, the debate still rages: Is "Nino" Scalia a brilliant and original jurist who bravely harnesses the Founding Founders' original vision to our contemporary jurisprudence, or just a political partisan in robes who provides intellectual window dressing for our society's basest instincts?

Bruce Allen Murphy's Scalia: A Court of One carefully sifts the vast record, calling him our first celebrity Supreme Court justice. While he's highly critical of Scalia, Murphy, a professor of civil rights, always carefully marshals overwhelming evidence to support that criticism.

Scalia's tenure on the court -- he's now among the 20 longest-serving justices ever -- has coincided with a coarsening of political debate in the country, and the book skillfully describes how Scalia's departure from the high court's traditional decorum has played at least a small part. In 1986, the nomination of this deeply conservative justice won a 98-0 nod from the full Senate, something that could scarcely be imagined today. Murphy notes archly that as the first Italian-American justice, he was a beneficiary of affirmative action, a policy he had railed against.

Even veteran court-watchers (I write this as one who covered the court in the 1980s) have been studying Scalia for so long that it's easy to forget how much he's changed the whole dynamic of being a Supreme Court justice. The book serves as a useful catalog of those changes.

On his very first day of oral argument, Scalia signaled that he would be no unobtrusive apprentice, as was the court's tradition for new justices. He so monopolized the questioning of an attorney that Justice Lewis Powell whispered to Justice Thurgood Marshall, "Do you think he knows that the rest of us are here?"

Raising eyebrows even higher, he embarked on a series of paid teaching and speaking appearances, where he sometimes dished about court decisions and even occasionally rendered his opinions on cases pending before the court, testing the limits of traditional ethical boundaries.

But it was his "textual originalism," a literal reading of the intent of the founders at the time they wrote the Constitution, that was his most radical act and the real source of his lasting influence. Ridiculed by some as amateur historiography, this legal approach is now baked into the court's deliberations. Even the liberal wing must at least account for it.

At 500 pages and another 100 in endnotes and bibliography, this volume, the product of eight years of work, is perhaps more than the average reader might need to know about the subject. The author is sometimes guilty of the journalistic sin of emptying his notebooks, getting bogged down in relatively minor cases, though generally not long enough that the narrative force lags. But to his credit, Murphy does a good job of translating the court's hidebound traditions into approachable language.

The author illuminates one of Scalia's most formative periods, his time teaching at the University of Chicago, a "laboratory for social Darwinism." Murphy makes a compelling case that Scalia's maddeningly condescending manner -- providing uninvited legal tutorials to such formidable thinkers as Justice Sandra Day O'Connor -- was really a product of his personal insecurities.

Murphy writes that early in Scalia's career, a lawyer observed that he "comes across as a knife-fighter, but a friendly knife-fighter." But aside from his periodic "charm offensives" pegged to the publication of a new book, he grew considerably less cuddly with age. Scalia reveled in pricking his many critics on the left. He often boasted of his reverence for the dead Constitution, dismissing progressive hosannas for the living document that could be adapted to fit the times.

Whether that bile can be traced to his emotional insecurities, his upbringing in a strict Catholic home, or a vestige of his training as a college debater, the chronicle of his bitterness can be startling when assembled in one place. Scalia was given to swatting away persistent criticisms that the Supreme Court improperly handed the presidency to George W. Bush with a simple message: "Get over it." So vicious were his personal attacks on fellow justices in various opinions that Supreme Court clerks privately dubbed him "Ninopath."

Like anyone with a long public career, he was the beneficiary of a few lucky breaks. Just a year after Scalia was elevated to the high court, Senate Democrats blocked the nomination of his former colleague on the D.C. Court of Appeals, Judge Robert Bork, a towering intellectual figure on the right. Ted Kennedy's ringing line about Bork's America being "a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters" helped launch the culture wars. But it also meant Scalia would become the sole spokesman for the court's right flank. The mute Justice Clarence Thomas, whose wholesale dismissal of court precedents once led Scalia to obliquely label him a "nut," provided no competition there.

"The vote was as much of a turning point for Scalia as it was for Bork," Murphy writes. "Scalia was now completely free of the intellectual shadow of Robert Bork. He and he alone would represent the original interpretation on the Supreme Court."

The book argues that he passed up the chance to have greater influence by following his lone-wolf temperament rather than becoming a consensus-builder of the court's conservative wing. But Murphy perhaps underestimates how ultimately influential Scalia has been. His forceful words and uncompromising persona will bolster the right long after he's gone.

As with the man who appointed him to the nation's highest court, Ronald Reagan, Scalia's legacy will serve as an emotional rallying point for the right, even decades after he passes from the scene. In that regard, he may have the last laugh. As horrifying as it may be for liberals and even many centrists to consider, Nino's court of one just may echo down through the ages of American jurisprudence.

[John Ettorre is a Cleveland-based writer whose work has appeared in more than 100 publications, including The New York Times and The Christian Science Monitor.]