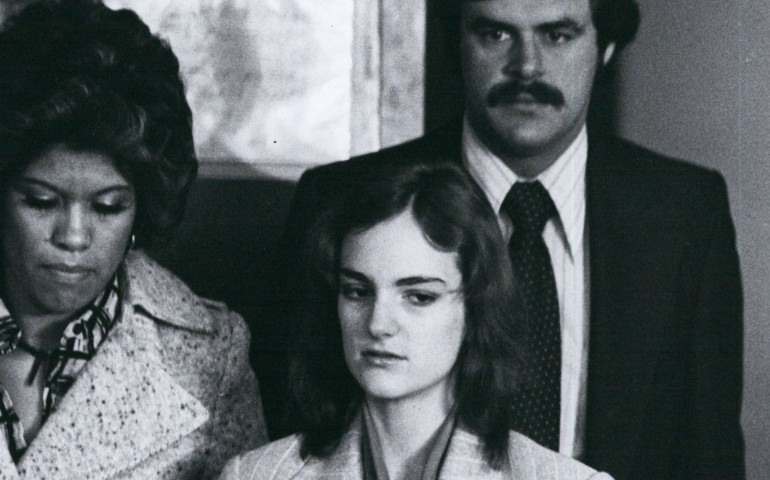

Patty Hearst at the Redwood City Jail is taken to court on Feb. 2, 1976. (Newscom/USA/ZUMAPRESS)

AMERICAN HEIRESS: THE WILD SAGA OF THE KIDNAPPING, CRIMES AND TRIAL OF PATTY HEARST

AMERICAN HEIRESS: THE WILD SAGA OF THE KIDNAPPING, CRIMES AND TRIAL OF PATTY HEARST

By Jeffrey Toobin

Published by Anchor, 480 pages, $16.95

There has been a recent spate of books about radicals of the 1970s, doubtless a soothing counterpoint to our own continuing conflicts: "Surely, this too shall pass." Now we have Jeffrey Toobin's account of the 1974 Patty Hearst kidnapping.

His book and others recall George Orwell's 1944 remark about history being written by the winners. Orwell's implication is that such history may well be false. Hearst's kidnapping remains a contested event. See Hearst's own contradictory version in her 1982 Every Secret Thing.

Toobin aims at setting the record straight, letting the discerning reader decide. Popularized history has taken a beating the last few decades, especially from television, given its quest to dramatize the past (and the present). History is now written by entertainers.

The Hearst case certainly was entertaining. Unfortunately, it echoed, in one important way, a more somber event in American history, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Jack Ruby's shooting of Lee Harvey Oswald on live TV forever raised the spectacle bar, and the Hearst case equaled it in the televised immolation of the core of the ragtag Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA).

Toobin is not new to sensational contemporary history. His 1996 The Run of His Life: The People v. O.J. Simpson shares a remarkable number of personalities that turn up in American Heiress. His 1999 volume on the Clinton scandals, A Vast Conspiracy, reveals yet more links of past and present. We now live in a post-spectacle age.

The radical rampages of the late '60s and the early '70s were an offshoot of globalization, a term not much used then. "Bring the war home," though, was an often-heard slogan, and that's what happened.

By 1973, when the SLA arose from do-good outreach to the California prison system, things had quieted down a bit. Crime had shifted to Washington, D.C., as Toobin lists: "The nation watched in astonishment" the Senate Watergate Committee at work, the "cratering" economy, the resignation of Vice President Spiro Agnew, etc.

The SLA's bloody debut, its killing of Marcus Foster, the African-American school superintendent of Oakland, California, well-described by Toobin, was generally denounced by far-left groups. Yet kidnapping Patty Hearst seemed to resurrect the SLA's reputation. For a group of fewer than 12 individuals, they all, especially their one-and-only black member and titular head, Donald "Cinque" DeFreeze, had ambition and big dreams. The SLA's murderous folly was fueled by good old American get up and go.

Toobin credits the Tupamaros of Uruguay as the SLA's "model" for kidnapping: "Kidnapping as opposed to murder — this was what passed for moderation in the SLA."

Toobin and the SLA needn't have gone to Uruguay for their model, since during the first three months of 1972 there was a well-covered trial in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, of seven radicals, six of them Catholics, who were charged with plotting to kidnap Henry Kissinger, an individual at least as famous as Patty Hearst. Kissinger's alleged wannabe kidnappers were certainly in the news.

Another thing largely absent from popular memory, and nothing that Toobin concentrates on, was the fact that Hearst was raised a Catholic, and that her mother, a fierce and devoted one, sent her to a number of Catholic schools. There, no surprise for a young woman of her generation, she turned rebellious.

As the Jesuits instructed, allegedly quoting St. Francis Xavier, "Give me the child until he is 7, and I'll give you the man." Well, the same goes for Patty Hearst. It's illuminating how many Catholics play roles in American Heiress: attorneys, radicals, FBI agents, journalists.

Hearst's post-trial bodyguard, and eventual husband, Bernard Shaw, was picked as a protector by her Catholic attorney, Al Johnson, because Shaw "was married with two young children and had been named the Catholic man of the year in public service by the Archdiocese of San Francisco." Patty found him a good divorce lawyer.

Frequently, in Toobin's account, this sort of remark pops up: "Patricia had said 'Olmec monkey,' not 'Old McMonkey.' (The FBI transcribers, like many people in law enforcement, were probably Irish Americans.)"

Catholics everywhere. Patty's "brainwashing" defense at her trial did not succeed. Brainwashing was a popular term at the time, thanks to Hollywood, replaced later by the Stockholm syndrome. (Now it would be "radicalized by the internet.") But such reasoning did help win her a commutation from President Jimmy Carter in 1979, and, eventually, a pardon from President Bill Clinton.

Her pleas to Carter were enhanced by the 900-plus deaths of the Rev. Jim Jones' religious-cult followers in Guyana in 1978. Jones, too, had wandered into the Hearst case orbit, volunteering to aid the free food fiasco.

As Toobin points out, a number of people, not just Patty, had been changed by those tumultuous years: members of the SLA; countless young people; even her father, Randolph Hearst, though not evidently her mother, Catherine. The Hearst marriage disintegrated by the end of the trial.

Patty's transformation at the hands of the SLA was more a religious conversion than any sort of brainwashing. She was ripe for change, living with Steven Weed, everyone's favorite whipping boy (including Toobin's), her former tutor and high school catch — meaning, as a high school student, Patty set out to snag him and she did. Hard to picture that going on today.

Patty's deprivations while kidnapped would have appealed to, say, St. Mother Teresa: Patty's imprisoning closet a cave, her diet an eremite's bland gruel, her torments a veritable dark night of the soul. Though Toobin doesn't follow this analysis, his thoroughly engrossing book, which a new generation of readers will profit from, confirms it. Patty turns the tables on her kidnappers, and they become her disciples.

The reason Patty wasn't killed in the televised house conflagration was that she and the SLA's married couple, the always quarreling Harrises, were allowed to go out and run errands, taking Patty along, to the opposition of some of the gang. But Patty's wishes prevailed: out of the squalid quarters into the sunshine and fresh air that eventually saved her life. She continues to prevail today.

[William O'Rourke is professor emeritus of English at the University of Notre Dame. An updated edition of his 1972 book, The Harrisburg 7 and the New Catholic Left, appeared in 2012.]