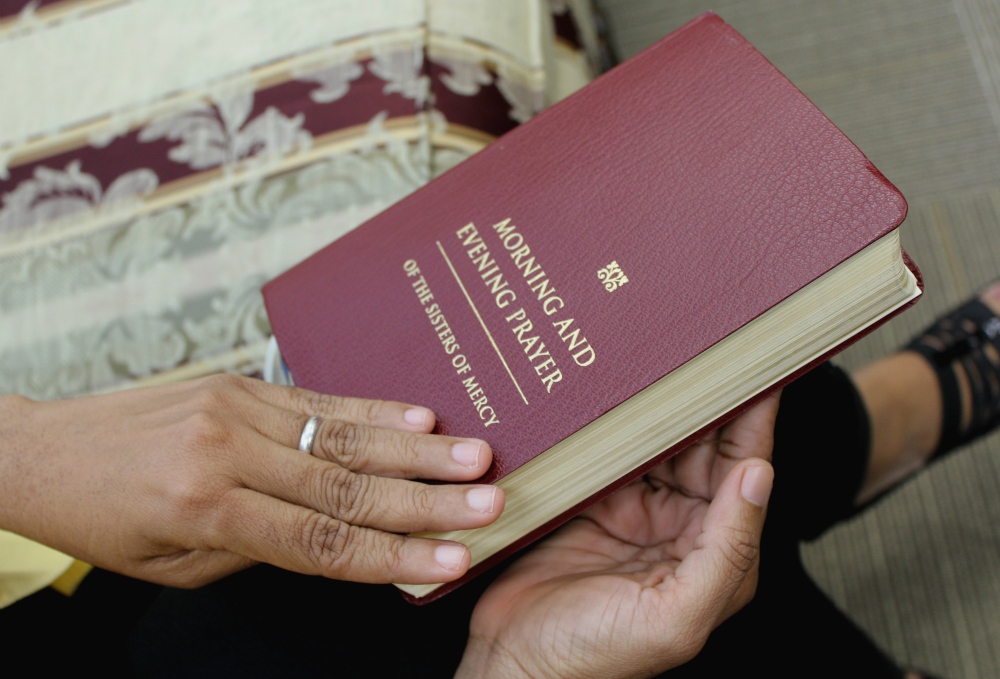

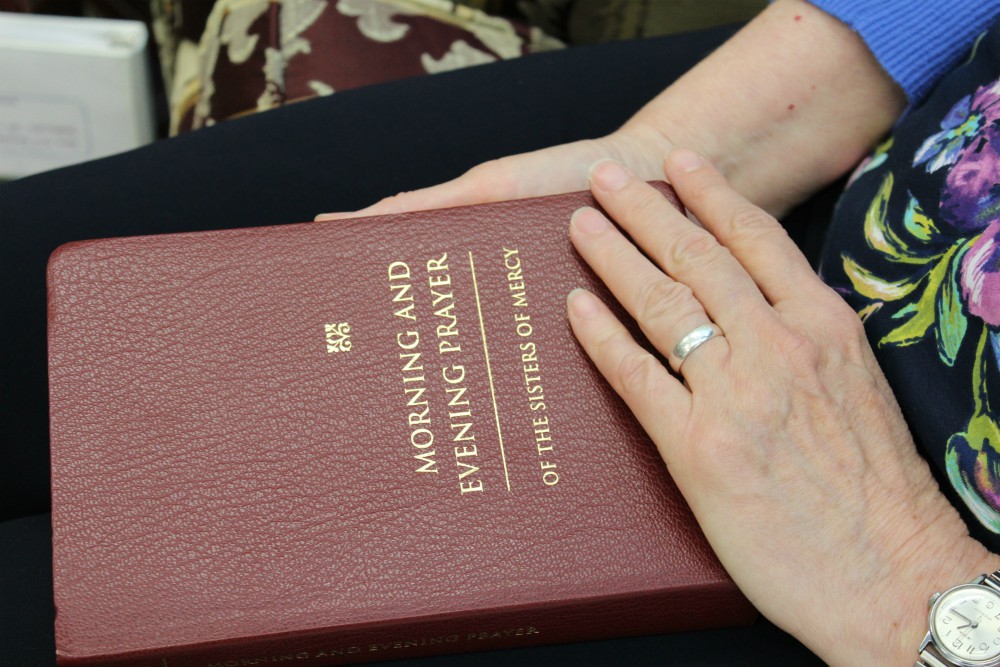

A Mercy sister uses the institute’s "Morning and Evening Prayer of the Sisters of Mercy." (Provided photo)

In women's religious congregations and communities across the U.S., members join in the Liturgy of the Hours, described as the daily prayer of the church. But while the practice may be universal, the prayers are not all the same.

Some congregations of women religious in the U.S. — independent of each other — have created their own versions of the Liturgy of the Hours, featuring inclusive language and prayers conveying their respective charisms. The efforts began a few decades ago, and in some cases continue to today.

"We wanted a prayer book that would reflect who we are," said Dominican Sister of Peace Anne Lythgoe.

The Mercy Sisters, Dominicans, Franciscans and others tackled the challenge, along with a Carmelite sisters community (formerly of Indianapolis) that published a widely-used People's Companion to the Breviary in 1997.

The congregations' work reached far beyond their own members as they gathered input from across the U.S. and around the globe. Teams of theological and biblical experts delved into writing petitions, translating psalms, selecting music, revising the doxology and blessings.

The Liturgy of the Hours, or Divine Office, is described on the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' website as the daily prayer of the church. Priests, religious and laypersons are accustomed to pausing periodically to join in this universal practice throughout the day and evening.

The four-volume Liturgy of the Hours was originally published in 1974, with the latest revisions ongoing since 2012, at the behest of the bishops' conference. The one-volume Christian Prayer, published in 1976 as a condensed version of the four-volume set, has not been revised since that date.

The office consists of five sets of psalms, canticles drawn from the Old and New Testament, Scripture readings, petitions, prayers and blessings in a four-week cycle for most religious congregations. Antiphons and other elements specific to the liturgical seasons are added.

Cloistered orders such as the Poor Clares or Trappistines pray the seven canonical hours: lauds (morning prayer), terce (midmorning), sext (midday), none (midafternoon), vespers (evening), compline (night) and matins (office of readings).

Advertisement

As the 20th century came to a close, communities of women religious were consolidating their ministries and, in some instances, their congregations. Yearning to retrieve a sense of praying "in common" in a manner and in words that matched their current reality and sensibilities, as Mercy Sr. Sheila Carney explained, congregations of women religious determined the existing Liturgy of the Hours to be inadequate in reflecting these concerns.

"People were tired of the old office and tired of sexist language," Carney said.

The variations on the Liturgy of the Hours created by these women religious congregations have been widely shared with other religious and laypeople, with some available in electronic versions. Lythgoe provided her reasoning for the popularity of the prayers: "It's meant to be communal."

Morning and Evening Prayer of the Sisters of Mercy

When the idea arose in the 1990s of creating an office for the Institute of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas, Carney served on the writing committee.

"It's one of the most significant projects that we've done as an institute of spirituality," said Carney, who now works at Carlow University, Pittsburgh.

The Mercy editorial committee discussed the best way to draw together sources for liturgy, music and writing prayers, Carney recalled. Their own Mercy heritage also played a major role in the composition of the new Hours.

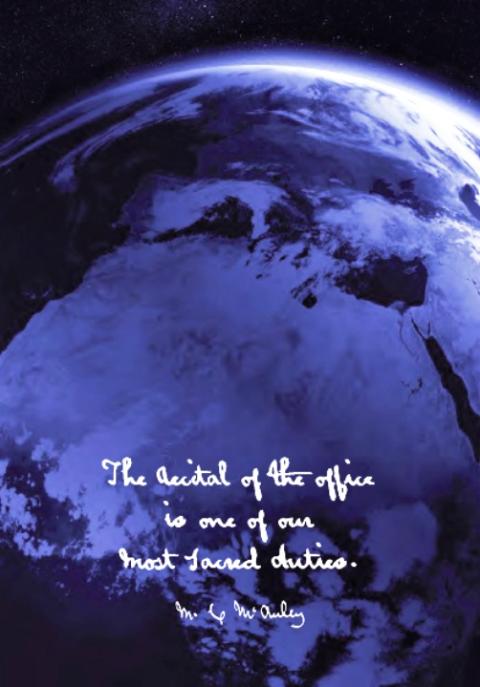

A page from "Morning and Evening Prayer of the Sisters of Mercy" illustrates a quote from the order's foundress, Catherine McAuley: "The recital of the office is one of our most sacred duties." (Provided photo)

"Many prayer texts are based on the words of Catherine McAuley and on documents central to Mercy life," reads the book's Introduction. "Intercessions and prayers have been written to voice our corporate concerns."

The inclusion of certain saints' feasts was based on foundress McAuley's Rule, where she listed about 15 saints she considered the institute's patrons, along with major feasts celebrated throughout the church and patronal feast days of the 13 countries where Mercy Sisters serve, Carney explained. That allowed for the book to remain a reasonable size.

When it came to the psalms, Carney said, "We handled that by selecting multiple translations and sent them out to biblical scholars." Considerations for determining the best translation included whether the translation of a given psalm conveyed the desired meaning, and the ease with which it could be sung.

The decision to use the translation of the psalms from the International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL) as the most viable came at a fortuitous time, Carney said. Shortly after the Mercy's Morning and Evening Prayer was published in 1998, the ICEL inclusive language translation was forbidden for liturgical use, following a letter of condemnation two years earlier by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, who was at the time prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

As for style, the Mercy Sisters selected what is known as the cathedral office. Rather than a combination of three psalms and canticles that is more common, one is used, along with the other readings, petitions and prayers. "The intention was not to make the office shorter, but to allow for greater reflection during the prayer," Carney said.

As for petitions, the editorial committee put out a call to all sisters in the institute. The committee received more than 70 lists of petitions, which were matched up to the days of the four-week cycle.

Arranging the psalms, petitions, readings and prayers was the most arduous part of the process, Carney acknowledged. Reciting certain psalms on given days, or certain themes, were understood, such as Psalm 51 on Friday, or Wednesday being the day to pray for the institute's new members. The rest was completed with deep reflection and consideration.

Psalm tones were added in the front of the book, for those wishing to use chant during the office. "We want people to be as creative as they choose to be in the use of the book," Carney said.

The Mercy editorial committee discussed the best way to draw together sources for "Morning and Evening Prayer." Their own Mercy heritage also played a major role in the composition of the new Hours. (Provided photo)

Carney retains a humility about her role, which was writing many of the concluding prayers. "I have reflected and said many times that probably the most sacred responsibility is choosing the words which the sisters will pray," she said.

Once completed, the book was published and distributed. A video was produced and a ritual composed to commemorate the moment in the institute's history. "We treated it as a sacred moment," Carney said.

An extensive training was held in all the regions for the sisters. "We brought them all together and worked through the book and all its options with them so that, in local situations, sisters would feel comfortable with using and adapting it," Carney said.

The Sisters of Mercy have uploaded their Morning and Evening Prayer onto the internet, where it can be used by anyone for free.

"Occasionally, we get a note from somebody about how much they enjoy the book," Carney said. She is encouraged by the response. "People are still appreciating the book and feeling supported by it." Other religious communities have even requested permission to use the petitions in their own prayers.

Though completed more than 20 years ago, Carney observed, "The book has a freshness to it still."

Dominican Praise

For Lythgoe, now a member of the Dominican Sisters of Peace leadership team in Columbus, Ohio, being exposed to the Sisters of Mercy's version of Morning and Evening Prayer in the late 1990s proved an inspiration. She recognized how a customized office could reflect one's own religious family.

Other Dominican sisters from across 17 U.S. congregations felt the same. Adrian Dominican Sr. Maribeth Howell related how, even before the project really started in 1999, the topic of having an office common to the order would be randomly discussed at meetings and social gatherings.

Dominican Sr. Maribeth Howell (Aquinas Institute of Theology)

A steering committee of five sisters, including Howell, was formed and met in 2001 to list the guiding principles for the work, she said. Among those points, the book was meant to diversify the names and images used of God, increase the use of feminine imagery, and reduce the frequency of terms such as Father, Lord and King, while respecting the dynamics of the text.

"I think it represented our diversity and at the same time our attempt at unity," Howell said.

Howell got involved as one of the translators on the project, when existing translations were unable to be used. She was released from her full-time position teaching Old Testament at St. Mary Seminary in Cleveland in mid-2002 and spent a year translating the psalms from Hebrew into English.

A group of other translators handled the Old and New Testament readings, as they worked with several liturgists from different schools of thought, Howell said. "The liturgists kept us in line, kept the elements straight and identified the psalms to be used."

The project faced an obstacle when the company initially scheduled to print the book objected that the Dominicans' translations were too close to those already copyrighted, Howell said. Realizing that if a translation is done correctly, it will be similar to those done by others, it still took some work to clear up the matter to move forward.

Those involved in the real conglomeration of work, as Howell phrased it, are represented in a list at the front of the book, featuring dozens of "magnificent and very talented" people who contributed to the final product in significant and different ways.

Based on pre-orders, the 2005 printing of Dominican Praise totaled 5,000 copies, according to email archives from the Sinsinawa Dominicans.

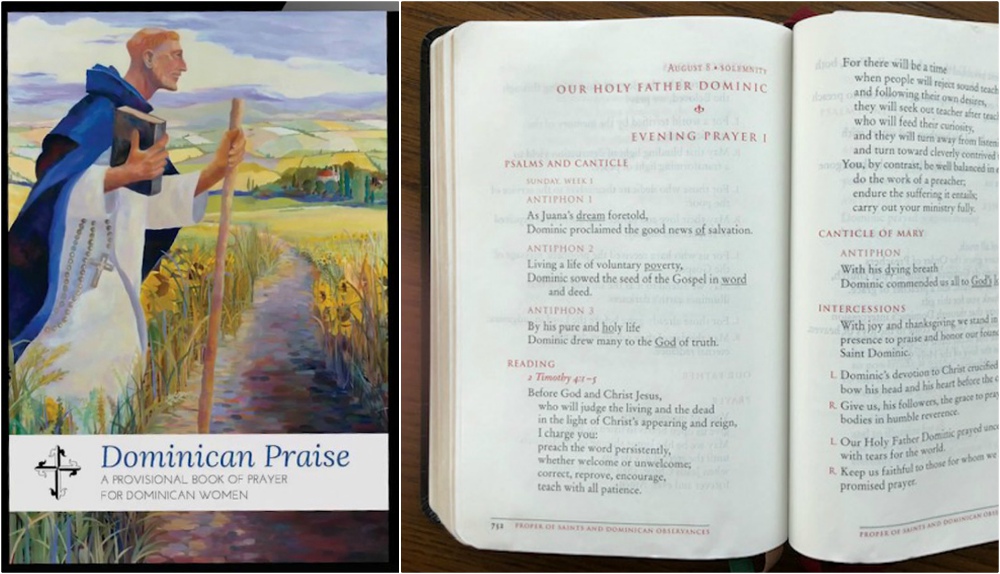

Left: The Kindle version of "Dominican Praise: A Provisional Book of Prayer for Dominican Women." Right: Special text for the feast of St. Dominic is featured in "Dominican Praise." (Provided photo)

A group of Dominican sisters even recorded a two-CD set chanted in simple psalm tones for selected morning and evening prayer drawn from the new book.

Since that time, communities that purchased the book would share extra copies with communities that didn't have them, Lythgoe said.

Dominican Praise: A Provisional Book of Prayer for Dominican Women was released in a version for Kindle in 2018, Lythgoe said. On one level an ecological consideration, the electronic edition offers adjustable font size that has proved an asset for sisters with impaired vision. Another consideration involved making the office available to a wider audience.

"The project to convert a printed book to an electronic edition took three years and represents the work of many Dominicans and lay partners," Lythgoe said. "I'm very proud of it."

The Benedictine Hours

While Benedictine communities have been adapting the Liturgy of the Hours for centuries, the Benedictine sisters of Our Lady of Grace Monastery, Beech Grove, Indiana, began using their community's first version of an inclusive Liturgy of the Hours in the 1980s, according to Sr. Marie Therese Racine, director of liturgy for the community of more than four dozen women.

Benedictine Sr. Marie Therese Racine (Provided photo)

The Benedictines draw their mandate for the task straight from the sixth-century Rule of St. Benedict.

Chapter 18 of the Rule describes the order of the psalmody, with an interesting loophole in Verses 22-23: "Above all else we urge that if anyone finds this distribution of the psalms unsatisfactory, he should arrange whatever he judges better, provided that the full complement of one hundred and fifty psalms is by all means carefully maintained."

"We've arranged the psalms so we pray all 150 in four weeks," Racine said, rather than the entire 150 psalms in one week, as St. Benedict originally stipulated.

The Beech Grove Benedictines, and many monasteries of Benedictine nuns and monks across the U.S., spent years on their respective versions of the Hours.

The Beech Grove sisters initially considered published versions of the psalms, the Grail translation and two from ICEL, Racine said. Because the Benedictines usually chant at least half the office, how well the psalm translation lent itself to singing was weighed with how it best conveyed the meaning.

"We've gone about it in our own way," Racine said.

The Erie Benedictines' 300-page inclusive psalter, titled "That God May Be Glorified" (Provided photo)

Each monastery's version is unique to its respective community, in that the selection of psalms, readings and prayers for given days in the cycle can differ — even the number of weeks in the cycle.

The formatting can differ, as well. Rather than formally publishing the volume, binders are used to contain the pages. St. Placid Priory, Lacey, Washington, for instance, has compiled one binder for each week of the four-week cycle. The sisters of Mount St. Benedict Monastery, Erie, Pennsylvania, divided the pages in separate binders for morning prayer and evening prayer, with a booklet for midday prayer.

As the community changes, so does its needs, Racine said. Thus, the content of Our Lady of Grace Monastery's office is periodically reexamined. "It's kind of an ongoing thing."

Most Benedictine monasteries have not formally published their version of the Hours, mostly due to copyright limitations. The Erie Benedictines, though, have their 300-page inclusive psalter, titled That God May Be Glorified, with a five-week cycle of psalms, for sale through the Benetvision website.

Franciscan Morning and Evening Praise

The number of Franciscan religious communities that follow the Third Order Rule — even in just the U.S. — would be difficult to count. The Franciscan Federation, formed in the 1970s, brings these communities together for an annual conference when a number of topics are discussed.

Around the year 2000, the conference included an informal survey to determine whether to create an office specifically for the Franciscans, recollected Tiffin Franciscan Sr. Ellen Lamberjack.

Original artwork decorates the pages of "Franciscan Morning and Evening Praise." (Provided photo)

At the time, Lamberjack was serving a three-year leadership term, culminating as president of the Franciscan Federation. The leadership team organized compilation of a sample of such an office, which was taken to the following year's conference.

Lamberjack was asked to chair the task group for what became the Franciscan Morning and Evening Praise book.

Meetings were held in 2002 and 2003 in Chicago, where participants joined to assist with the project, Lamberjack said. As parts of the book were put together, a coordinator sent them to some of the 40 Franciscan communities, which used them for prayer in two-month segments and submitted feedback.

"Those evaluations were invaluable to us," Lamberjack said.

Revisions were presented at the 2006 Franciscan Federation conference, so members would have a sense of how the book would look. More feedback required additional corrections and editing, Lamberjack said.

Franciscan Sister of St. Joseph Ann Lyons served as the Franciscan Federation's executive director in 2009, when 10,000 copies of Franciscan Morning and Evening Praise were printed. "Everybody was waiting for it to come to fruition," she said. The yearly updates at the conferences had the members excited.

Lyons noted how the Franciscan flavor permeates the book. Each week of the four-week cycle is themed to Franciscan values of penance, poverty, contemplation and minority — or humility, she added. In the text itself, simplicity and the pursuit of peace through justice figure prominently, along with other key aspects of the Franciscan charism.

For each of the hours, a Scripture reading is followed by an excerpt from a Franciscan text, Lyons said.

In all, Lamberjack said, 784 people were involved to some degree in the project, which took almost a decade from the initial survey to published book.

Franciscan Srs. Ellen Lamberjack, left, and Ann Lyons (Provided photos)

Demand for Franciscan Morning and Evening Praise required a second printing in 2014. Tau Publishing of Phoenix handled the revisions, which included splitting the one-volume original into two hardbound volumes. Also, "due to the high cost of licensing the music we were unable to print it in this new edition," the website reads.

"As I look back at it now, I'm pretty amazed at all we did," Lamberjack said.

Ursuline Book of Prayer

Though the Ursuline Sisters encompass the globe with their ministries, the effort to create an office specifically for the order started at Mount St. Joseph in Maple Mount, Kentucky.

"This thing emerged in the mid-'90s and it's still not done," chuckled Ursuline Sr. Cheryl Clemons, who, with Srs. Ruth Gehres and Mary Matthias Ward, started the project.

Clemons, a theologian, researcher and writer, later took on the majority of the work for the office while also serving at the Ursulines' Brescia University in Owensboro, Kentucky, until her retirement in 2019.

"We were aware the Benedictines and the Franciscans had their own versions," Clemons said. The Ursulines' initial goal was a one-volume book, but, over the years, it grew to two volumes, then three — the last of which should be completed by Easter 2021.

"What we wanted to do wouldn't fit in one volume," Clemons said, noting how using a 14-point font to make it easier reading for older sisters added to the page count.

A major challenge for Clemons involving balancing inclusive language with traditional translations, along with modern saints and more customary ones. "Some sisters weren't into inclusive language at all," she said. "We didn't want it to be inclusive in-your-face."

So, where a line of a psalm might mention the "God of Jacob," Clemons left the wording, phrasing the antiphon with "God of Leah."

Ursuline Sr. Cheryl Clemons (Provided photo)

The Ursulines, too, were caught by the ICEL translation controversy of 1998, so Clemons pulled together a psalter from six different sources.

Economy was key. Being able to use only 30 of the Grail psalms before having to pay for the copyright permission left her to find other sources, such as a Franciscan version from the 1980s, adaptations of Joseph Arackal's 1992 The Psalms in Inclusive Language, and others from the Erie Benedictines.

In many cases, the Ursulines were given permission to use the texts without payment, because the office was not intended to be mass marketed, Clemons said.

Over the three volumes, the first had a printing of 1,000 copies, the second, 750, and the third will have a printing of 500 copies, Clemons said.

Clemons ensured the Scripture readings used during liturgical seasons such as Advent and Lent were not repetitive. "Each day has its own Scripture reading," she said. "We decided to give people more access to Scripture."

Some of the Scripture readings are longer than what is found in the common Liturgy of the Hours, since the Ursulines do not pray the office of readings, Clemons said.

The special feasts are not all canonized saints either, she explained. Those who have inspired in the fields of education, justice and peacemaking — such as Dorothy Day, Matt Talbot and Martin Luther King Jr. — are included as "commemorations" or "optional commemorations."

The biographies included for these special days reflect the subject's humanity, too, Clemons said. "The goal in creating these biographies is making them real people."

Clemons revised the sets of common offices in the book, used on days when specific prayers for a given saint are not provided in the Hours. "They seemed pretty narrow and pretty male-focused," she said of the commons found in the standard Liturgy of the Hours. Rather than a common of virgins, she created a common of consecrated religious — to be used for both men and women religious. The common of pastoral workers replaces the common of bishops, and so forth.

The music Clemons has included — also without having to pay for licensing — is not duplicated from the usual missalettes or hymnals. "These songs aren't found elsewhere," she said, and they are being inclusive.

Though Clemons has done a lot of the work on her own — "It's taken half my life," she said — she credits many others with proofreading the text, and Ursulines around the country for sending in original art, music and prayer services that she used as resources. "This has been a labor of love for a lot of people."

[Julie A. Ferraro has been a journalist for more than 30 years, covering many topics for publications across the U.S. She currently lives in Yelm, Washington.]