A banner in tribute to the National Health Service is seen outside St. Paul's Church April 29 in Belfast, Northern Ireland, during the COVID-19 pandemic. (CNS/Jason Cairnduff, Reuters)

Standing at Land's End, the most westward tip of England, and gazing out over the Atlantic, I know that America is out there somewhere — beyond the grey and rain-streaked horizon. Despite the cold, watery gulf that separates us, we are not "Two peoples divided by a common language," according to the quote often ascribed to George Bernard Shaw, but two nations ruled over by populist leaders who have more in common than that which might divide us.

From my living room, and with copies of the liberal newspapers in my hand, the recurrent picture painted of President Donald Trump is not altogether flattering. He is presented as an intellectually challenged leader who, for all of January, February and most of March, refused to countenance the reality of the coronavirus pandemic and took few steps to mitigate its potential impact.

On this side of the pond, Prime Minister Boris Johnson reflects his blond, bouffant American cousin, even going so far as to have taken a two-week holiday in February as the reality of the pandemic storm began to take shape and present an existential threat to the United Kingdom and the world.

Prime Minister Johnson was spared some degree of appropriate excoriating criticism when he succumbed to the coronavirus himself and was hospitalized with the subsequent suggestion that his life had hung in the balance. Further, and within days of his discharge from hospital, his fiancé (like Donald Trump, Boris is a serial polygamist and it has not been established just how many children he has actually fathered during his various marriages and affairs) gave birth to their first child and the tabloids were consumed with photos and narratives of another Johnson junior.

But here in the United Kingdom the mitigating factor that protects Prime Minister Johnson and his coterie of utterly inept adjutants is the presence of the NHS (the National Health Service). Indeed, as the 75th anniversary of VE Day was celebrated in May, we were reminded that one of, if not the, most cherished institutions arose in the wake of the conflagration that was World War II. Although inevitably poorly managed by our political leadership, and chronically underfunded, the NHS has been recognised as the jewel in our national landscape. It constitutes part of the "better normal" that arose from the Second World War.

However, it is a phrase coined during the First World War (to describe the relationship between the infantry and the generals) of "lions led by donkeys" that most aptly describes the contemporary view of the gallant NHS and their inept political masters.

Sister of Mercy in Sunderland, England, applaud during the Clap for our Carers campaign in support of the National Health Service April 30, during the COVID-19 pandemic. (CNS/Lee Smith, Reuters)

Thursday evenings see people gathering outside their homes to clap and applaud their NHS heroes — a feature covered on numerous television channels. Rainbow pictures adorn windows across the land saluting the role of the NHS, and even the elusive Banksy (an anonymous street artist) has donated a picture praising health-care workers to an NHS hospital in the southern town of Southampton that might be worth in excess of $1 million. One hundred-year-old Tom Moore, a World War II veteran known as "Captain Tom," recently raised nearly $40 million for the NHS by walking around his garden.

These instances attest to the fact that the HNS is viewed in the United Kingdom as the nearest thing we have to a national religion. "Obamacare" is sometimes touted as the American equivalent but, as the Linacre Quarterly (the peer-reviewed journal of the Catholic Medical Association) observed, The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 denies universal access to the care all might require.

"Many Americans have no better insurance coverage; and many face ever-increasing medical expenses, premiums, and deductibles. Millions remain uninsured. Immigrants lack access to basic health care. … Many working families cannot afford the high deductible plans they are compelled to purchase," wrote Donald Condit in the Linacre article, "Catholic Social Teaching: Precepts for healthcare reform" in 2016.

The loss of more than 33 million American jobs over the seven weeks covered by the coronavirus pandemic means that many former employees and their families have lost not just their income but healthcare insurance that came with the job. This can only add to the fear, anxiety and uncertainty that comes with sudden unemployment.

The fact that we will never be rendered destitute on account of medical bills is a given here in the United Kingdom and across Europe. Just over a year ago I celebrated my 60th birthday and rashly bragged, at a dinner party hosted by friends, that I had never experienced any underlying health conditions. My words came back to haunt me and the last 12 months have seen me diagnosed as suffering from hypertension, possible prostate cancer and chronic cataracts in both eyes. My doctor has prescribed me medication to reduce my blood pressure, invasive surgery to explore the potential cancer, which proved that I was mercifully free of the disease, and a procedure to have an artificial lens implanted in my right eye (the left will have to wait until the coronavirus age passes and non-urgent elective surgery can be resumed). And how much did this cost me? Nothing.

If I succumbed to coronavirus I would be admitted to hospital and receive exactly the same care that was afforded to Prime Minister Johnson — who was also treated in an HNS hospital (St Thomas', just across the River Thames from the British Parliament). Again, it will cost me nothing.

As a university lecturer I fear that my job might disappear if students do not return to campus in September. I am concerned that my daughters might not be able to return to school in the near future. But I never fear that I might not receive the best and most appropriate treatment were I a victim of COVID-19 or that such care might see me reduced to penury.

This care is a reflection of Article 25 of the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 which "Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services." This declaration was made the same year as Government Minister Aneurin Bevan's National Health Service first opened its doors.

Pope Francis himself asserted just a few years ago that "health is not a consumer good but a universal right, so access to health services cannot be a privilege." He went on to note that for too many people health care "is not a right for all but rather still a privilege for a few, for those who can afford it."

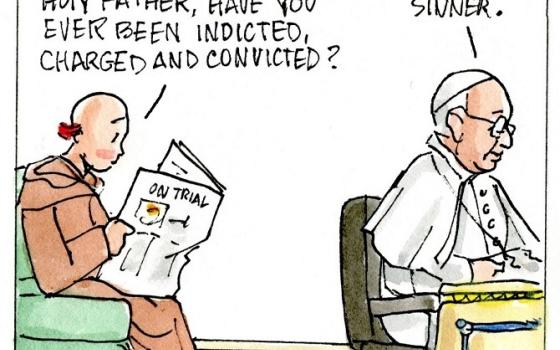

Such sentiments do not always endear Francis to senior churchmen, including some in America, who view the pope's teaching as dangerously influenced by the so-called "Marxist-inspired" liberation theology that arose in South America in the aftermath of the Second Vatican Council.

The impression given to us in the United Kingdom is that America regards such care as a manifestation of "socialism" (a euphemism for "communism":). This is utter nonsense. Can you imagine what it would be like for every American to rest assured that he/she would receive first-class treatment for any medical condition without the threat of bankruptcy? Private health care is available here in the United Kingdom and can allow the prospect of a shorter waiting time for normal elective procedures. But, if something goes wrong, then the patient is immediately transferred to an NHS hospital where the full gamut of emergency procedures are available.

Advertisement

Many of those Americans who dismiss any suggestion of universal health care have now inadvertently become the recipients of income support or unemployment benefit — surely an example of the "socialist" safety net that they are supposed to reject and ignore. Whether it be ensuring that a fellow citizen does not die because she cannot afford the insulin to treat her diabetes or supporting a family from being evicted from their home on account of a loss of employment — these are manifestations of a Christian society, a response to Jesus' command to "Love thy neighbor."

But, as the lockdown continues and the days and weeks pass with little to distinguish one from another, the question frequently asked is "When will things return to normal?" But rather than looking back to how things were in the "halcyon" days before the coronavirus, voices are beginning to articulate the hopes for a "better" normal.

Surely, for my many friends in America (and I spent more than a year there studying in Chicago and have visited many times since) the prospect of a Christian-inspired universal health care might constitute part of the "better" normal that comes out of this pandemic.

[Mark Faulkner is a university lecturer in London, England, where his specialist subject (other than a keen interest in promoting and applauding the work of the NHS) is the indigenous religions of Africa.]