(Unsplash/v2osk)

Death and deadliness seem to be all around us with no way out. In most recent update, the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation projected 295,000 U.S. deaths from COVID-19 by Dec. 1.

In the midst of an unabated pandemic and the federal government unleashing unnecessary violence on peaceful protestors, the threat of eviction looming for millions of renters, and loss of a $600 weekly unemployment bonus threatening the livelihood of millions, it seems as though we are collectively gripped by unnecessary death, destruction and cruelty.

People of conscience, truth and science lament that it did not have to be this way. While we need to maintain massive civil disobedience in the face of governmental injustice, there is greater hope in the Jewish and Christian mystical tradition of receptive generosity — God's welcome — that draws us into intimate and infinite sensitivity for every creature in the whole of creation.

As David Corn observes, "by now it's damn clear that Trump is a narcissistic sociopath who cannot express an ounce of regret over the deaths caused by the virus." The most damning evidence, Corn finds, is that Trump "cannot see that his own and much-cherished personal interests — notably, getting reelected — are aligned with the public interest of curtailing the pandemic."

Corn details numerous ways that "Trump cannot perceive or escape the vortex of his own self-destruction." The greater tragedy may be that a critical aggregate of people who still support the president hastens unnecessary death for thousands.

It seems as if the president's desire to constantly degrade others — Dr. Deborah Birx and Dr. Anthony Fauci only the latest in a long list — in order to fulfill his own ego and lust for domination reflects a deeper societal malaise and soul sickness.

More egregiously, public health officials have faced death threats for mask mandates in Orange County, California, Ohio, Green Bay, Wisconsin, and Stillwater, Oklahoma, that have resulted either in the dangerous relaxation of the mandate and/or officials resigning for their own safety.

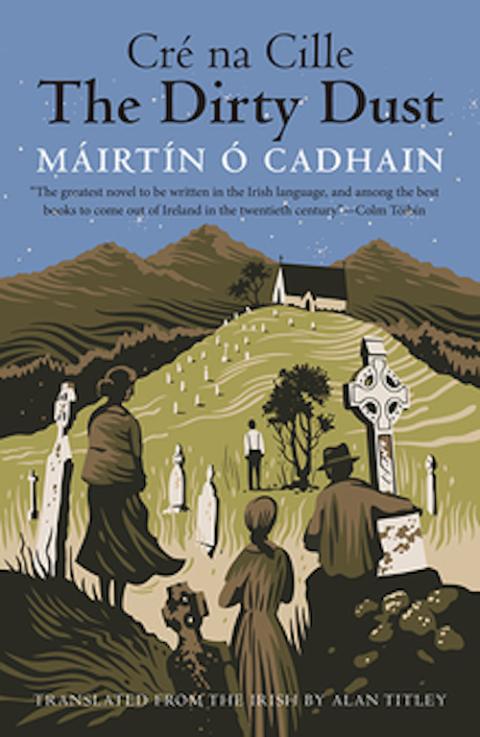

Cover art for "The Dirty Dust" (Yale University Press)

I feel like we are living Cré na Cille (The Dirty Dust), Máirtín Ó Cadhain's satiric novel of a cacophony of voices of dead people in a cemetery. Alan Titley explains that Cré na Cille, originally published in 1949, might be translated as "The Earth of the Graveyard," "Cemetery Clatter," "Crypt Comments," or "Coffin Cant" in his translation of the work (Yale University Press, 2015). Titley settled on The Dirty Dust because it maintains the rhythm of the original Irish and rings with biblical echoes "that dust we are and 'unto dust we shall return,' while not forgetting that what goes on below amongst the skulls and cross words is certainly dirty."

I found myself caught between deep belly laughter and tears as I read The Dirty Dust and wondered whether Ó Cadhain (1906-1970) was describing the continuation of life in physical death or people living as if they are dead. Each chapter's introduction or interlude is spoken by The Trumpet of the Graveyard.

The Trumpet of the Graveyard's announcement in the third interlude sounds like life in 2020: "Questions and querulousness nibble at joy and the carefree spirit. … Despair is overwhelming love. The shroud is being woven by the baby blanket, and the grave is being prepared instead of the cradle. Life is paying its dues to death."

Or, utilizing biblical scholar Eugene Peterson's translation of Luke 11:43-44, perhaps Jesus' indictment of the pharisees addresses us: "You love sitting at the head table at church dinners, love preening yourselves in the radiance of public flattery. You're just like unmarked graves: People walk over that nice, grassy surface, never suspecting the rot and corruption that is six feet under."

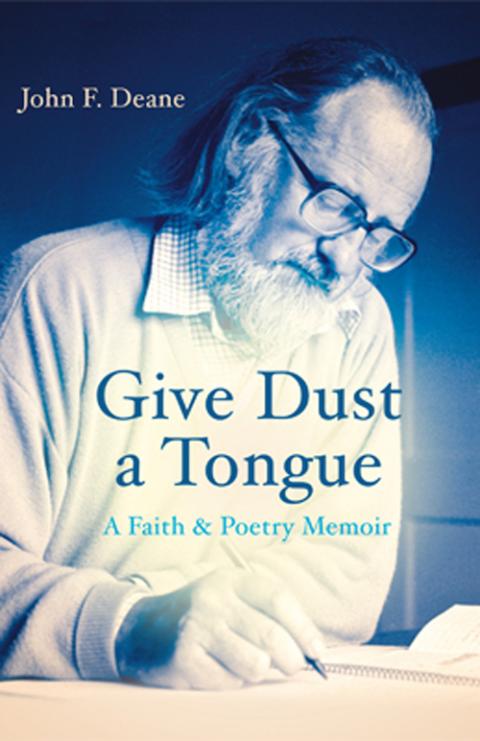

Cover art for "Give Dust a Tongue" (Columba Books)

And yet, as George Herbert's poem "Love (III)" notices "Love bade me welcome: yet my soul drew back, / Guilty of dust and sin." In his Give Dust a Tongue: A Faith and Poetry Memoir, the Irish poet John F. Deane engages Herbert in an imaginative dialogue about "Love (III)." Deane asks Herbert: "You speak, in your poems, a great deal about dust." "Love bade me welcome" is "Beautiful, but, guilty of dust?"

Deane imagines Herbert's reply: "Oh it was death calcined our hearts along with the Lord's to dust and ashes, so his life will turn our hearts to gold and make us just." In the midst of our dust and sin, Deane finds, "Grace alone can open the soul's most subtle rooms."

As Carmelite Sr. Constance FitzGerald describes the theological anthropology of St. John of the Cross in her essay "Transformation in Wisdom: The Subversive Character and Educative Power of Sophia in Contemplation," in Carmel and Contemplation: Transforming Human Consciousness, the human person is seen as an infinite capacity for God in the "caverns" — the "soul's most subtle rooms" — of the intellect, will, and memory.

She quotes John of the Cross' commentary on The Living Flame of Love where he explains that because the object of these caverns, namely God, "is profound and infinite. Thus, in a certain fashion their thirst is infinite, their hunger is also deep and infinite, and their languishing and suffering are infinite death.

Advertisement

As long as we fill the caverns of the intellect, will and memory with "human knowledge, loves, dreams, and memories that seem or promise to satisfy completely," FitzGerald explains, "the person is unable to feel or imagine the depths of capacity that is there."

Paradoxically, only when we become aware of the emptiness of these caverns, especially now in the midst of our fragility and breakdowns of all that we have invested our lives in, "the limitation of our life project and life love, and the shattering of our own dreams and meanings, can the depths of thirst and hunger that exist in the human person, the infinite capacity, really be felt."

Full of "dust and sin" we may be, "Love bade us welcome." That is, as we seem to be falling into an abyss of "dust and sin," God draws us into an infinite capacity for mystical sensitivity to the interdependence and bondedness of the whole of creation, to paraphrase Beverly Lanzetta's Radical Wisdom. Perhaps the simple act of wearing a mask might be a step whereby we welcome Love who alone opens the caverns of our being to mutual care and receptive generosity for all of our relationships. Death may yet be transformed into new life.

[Alex Mikulich is a Catholic social ethicist.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email notice every time a Decolonizing Faith and Society column is posted to NCRonline.org so you won't miss it. Sign up for it here.