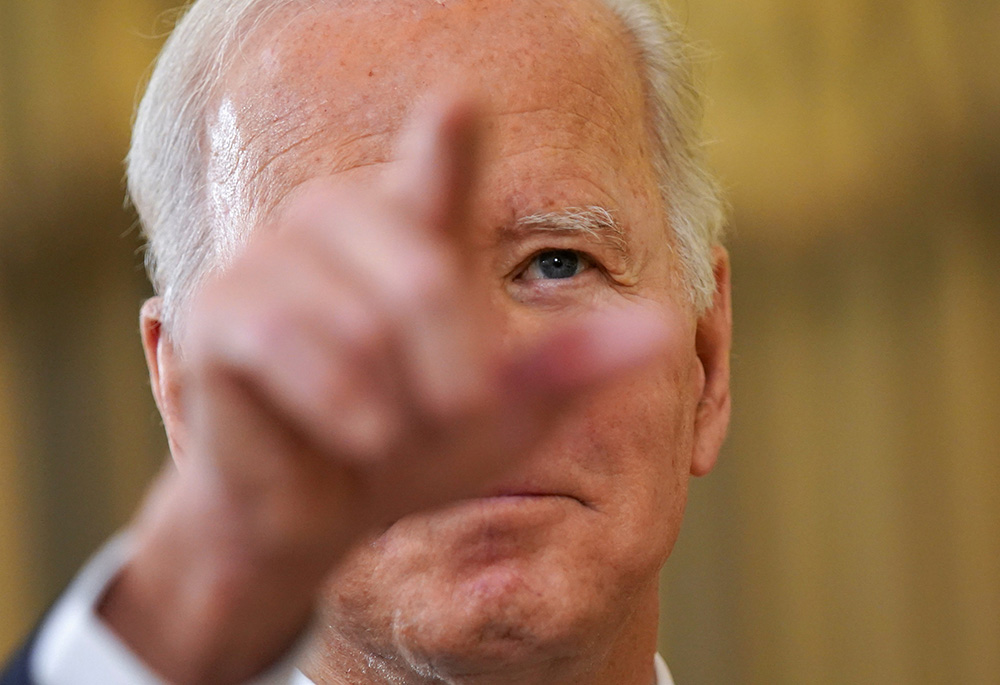

President Joe Biden delivers remarks on the November jobs report from the White House Dec. 3 in Washington. He convoked a two-day virtual summit on promoting democracy Dec 9. (CNS/Reuters/Kevin Lamarque)

President Joe Biden convoked a two-day virtual summit on promoting democracy Dec 9. This was the sort of thing that, if done 20 or 40 years ago, would have been focused exclusively beyond our borders. Not now. Now we are fighting for democracy at home as well, the fight is proving difficult, and Biden's Catholic faith has something to offer the cause.

In his opening address, the president noted that groups like Freedom House, which have been working on democracy promotion for decades, report that indicators of democratic vitality have been trending down worldwide. The president acknowledged that "democracy is hard. We all know that. It works best with consensus and cooperation. When people and parties that might have opposing views sit down and find ways to work together, things begin to work."

He added, "But it's the best way to unleash human potential and defend human dignity and solve big problems."

In advance of the summit, Jan-Werner Müller, a politics professor at Princeton, complained in a New York Times op-ed that Biden was selling democracy short. After complimenting Biden's summit planners for attracting all the right enemies, e.g. China and Russia — "You know you're throwing a good party if everyone who isn't invited keeps criticizing it." — Müller argued that the "real problem" with the summit was its "framing of the contest between democracy and autocracy as one about which can deliver the goods of growth and stability." That framing made it possible to invite authoritarians like Narendra Modi of India and Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil to the summit. Müller added, "Democracy is not just instrumentally valuable — if that were the case, we might give it up for systems that deliver more. It is valuable in itself."

And, sure enough, in citing his own achievements, Biden began with American Rescue Plan and the infrastructure bill, two policy achievements that focused primarily on the rebuilding the economy after COVID-19 and after years of underinvestment in infrastructure.

Müller's concern is valid but not exhaustive: Any government that does not attend to the material needs of its citizenry will be inherently unstable.

But Biden also defended democracy, per se, not just its consequences. "And as a global community for democracy, we have to stand up for the values that unite us," the president said. "We have to stand for justice and the rule of law, for free speech, free assembly, a free press, freedom of religion, and for all the inherent human rights of every individual."

The earlier noted reference to democracy being the best means for defending human dignity also gets at the non-materialistic qualities of democracy that are worth defending.

Advertisement

Last year, Rebecca Winthrop authored a report for the Brookings Institution about the need to reboot civics education in the 21st century, and offering some ideas about how to achieve that. She quoted the "father of American education" Horace Mann who wrote in 1848: "It may be an easy thing to make a Republic; but it is a very laborious thing to make Republicans; and woe to the republic that rests upon no better foundations than ignorance, selfishness, and passion."

Did Mann foretell the rise of Trumpism with that concluding trio of social ills?

Mann, of course, wanted nonsectarian education and that did not include Catholics. His school reforms included use of the King James version of the Bible, and he thought the text could "speak for itself." Catholics have never thought that the Bible was self-explanatory.

Besides, in 1848, Catholics were not exactly the strongest advocates of democracy! The 19th century witnessed an almost relentless attack on democratic values by papal teaching. "Here We must include that harmful and never sufficiently denounced freedom to publish any writings whatever and disseminate them to the people, which some dare to demand and promote with so great a clamor," wrote Pope Gregory XVI in his encyclical Mirari Vos ("On Liberalism and Religious Indifferentism"). In the infamous Syllabus of Errors, Pope Pius IX condemned the proposition that "The Roman Pontiff can, and ought to, reconcile himself, and come to terms with progress, liberalism and modern civilization."

Only with Pope Leo XIII's 1892 encyclical Au Milieu des Sollicitudes on the church and state in France do we see a positive opening to democracy with the pope calling on French Catholics to rally to the Third Republic, at least as a practical matter. Leo did not concede any democratic principles. Many, perhaps most, French Catholics demurred, and Leo's successor, Pius X, was as reactionary as Pio Nono had been. Even Pius XI, whose condemnations of capitalism and communism still ring with freshness even today, was no great partisan of democracy.

Durham University theologian Anna Rowlands has chronicled the rise of a focus on human dignity in church teaching during the pontificate of Pius XII, examining his wartime allocutions. These understudied documents really demonstrate the degree to which Pius, who was no liberal, came to see the value in democracy after experiencing the horror of its negation.

We are all familiar with the teachings of the Second Vatican Council, which affirmed democratic values in Gaudium et Spes, and provided a nuanced, profound teaching on religious liberty in Dignitatis Humanae that is still being received. Pope John Paul II was an unflappable defender of democracy, albeit not in the church. In Athens just last week, Pope Francis warned against a "retreat from democracy."

The church's greatest contribution to our understanding of democracy is that it gets the relationship of the individual to the group right, and it does so at a time when so many get that relationship wrong. Libertarianism, of both the left and the right, celebrates unbounded individual volition, and is always ultimately anti-democratic, eroding solidarity and the sense of communal obligation without which democracy withers.

On the other hand, identity politics, of both the left and the right, reduces persons to their membership in a group, resulting in a distinctly antisocial posture and inviting a flattened sense of human dignity.

Balancing the transcendent dignity of the human person with the recognition that the human person only flourishes in society is not easy, but it is necessary. The church's most distinctive intellectual bias through the centuries, to view conundrums as "both/and" rather than "either/or" propositions, is not only correct in this instance but critically needed.

It is funny in a sad sort of way, that whenever anyone talks about Biden's politics being influenced by his Catholicism, whether they seek to praise or to criticize, no one ever mentions the church's teaching on democracy and civic participation.

In his speech, Biden pointed to one secular area where this same balance between the individual and the group is rightly achieved: organized labor. "We're fostering greater worker power, because workers organizing a union to give them the voice in their workplace, in their community, and their country isn't just an act of economic solidarity," the president said, "it's democracy in action."

So it is. And it is more than coincidence that the first pope to show an opening to democracy, Leo XIII, was also the first to champion the rights of workers to organize.

This two-day summit will not refocus the country, let alone the world, on democracy such that we can all relax. In the op-ed already cited, Professor Müller laconically quotes Polish-born political scientist Adam Przeworski on the minimum standard for democracy: "a regime in which incumbents lose elections and leave office if they do."

It is a good time to embrace this kind of minimalist expectation, to remember that democracy is the worst form of government — except for all the others that have been tried. And that is enough to make it worth saving.