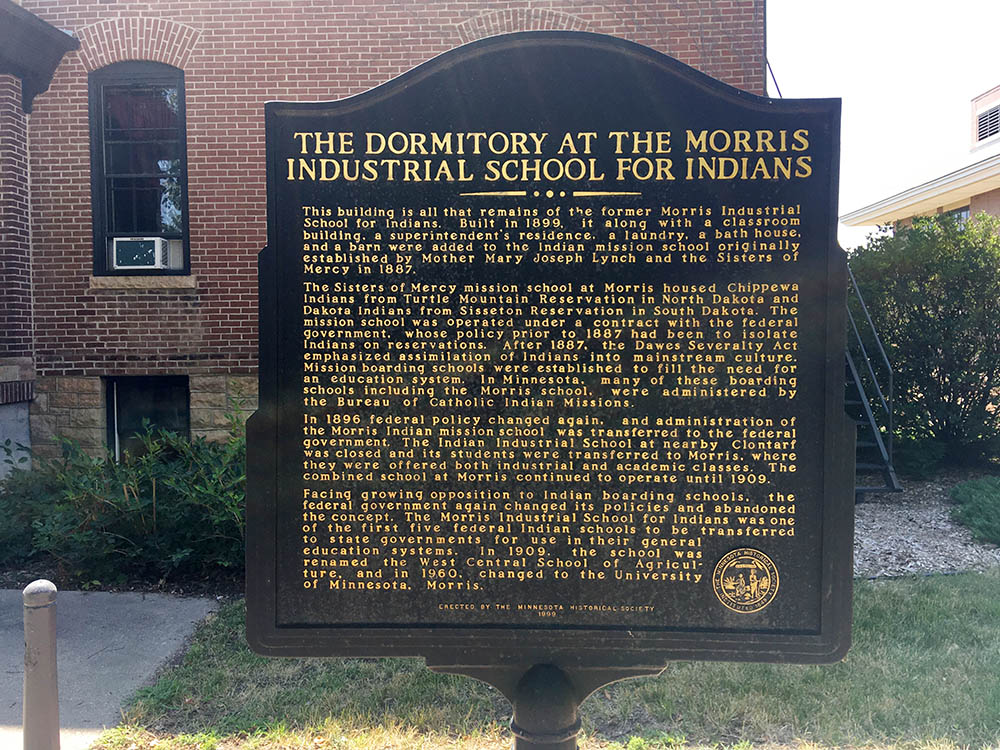

A marker erected by the Minnesota Historical Society marks the site of the dormitory of the former Morris Industrial School for Indians. (Courtesy of Elizabethada Wright)

Recent discoveries of the bodies of Native American children buried on the properties of boarding schools in Canada and the United States seem to be opening new avenues of research. One is an interest in the personalities who founded and managed these schools for the churches and governments — the context they lived in and their motivations.

For me, this interest was reflected in a lecture by Elizabethada Wright, a professor of English at the University of Minnesota Duluth, which the International Scholars of the History of Women Religious at Durham University in the U.K. presented online in January. Her presentation of her preliminary research focused on one such personality: Mother Mary Joseph Lynch, a Sister of Mercy who lived from 1826 to 1898. This preliminary research will inform a future piece she will co-author with Stephen Gross, archivist at the University of Minnesota Morris.

Although the lecture was brief and the focus was on the U.S. boarding school system in the 19th century, I learned a lot.

The boarding school system for Native American children as we know it dates from the 1880s, when there developed a drive to curtail culture of Indigenous people. Although different U.S. presidents at this time may have had somewhat different attitudes toward the Native Americans, some more humane than others, all agreed that they had to be integrated into the dominant white culture. Churches fell into the same mindset, and the Native American culture faced serious threats. Indigenous nations today are working to revive their cultures as much as possible.

Two things piqued my interest in Wright's presentation. One was early on, when she said Lynch opened a school in Morris, Minnesota, a small town where I was born that borders South Dakota and is not far from Canada. Another came after Wright's presentation in the question-and-answer segment, where a participant commented: "Culture always seems to trump the Gospel." The statement set me thinking about my own daily discernment.

As we listened to the story of Mother Mary Joseph Lynch's missionary efforts, it definitely seemed that the culture influenced how she carried out her mission.

Lynch was a Mercy sister from Ireland who lived through the Great Famine and came to the United States to evangelize through education. She opened many schools, most of which, according to reports, were highly successful. Lynch was seen as a trailblazer by some and, for critics, a troublemaker, particularly for clergy.

Even though she fell into following current cultural thinking about Native American education, she stood against patriarchal assumptions of society and church, something not uncommon for women religious throughout history.

This became clear in 1885, when a parish priest in Morris invited her and a group of her sisters to open a school there. Lynch followed her own lead, instead opening an elite school for girls from well-to-do families. The young women were taught French, painting and instruments. However, for reasons not known, the school did not take root — there were probably not enough well-to-do people in the area who had daughters desiring this form of education.

Nothing, however, deterred Lynch. In 1887, only two years after her first venture failed and she realized she needed to change direction, Lynch discovered a population she deemed in need of education: Native American children living near the Minnesota border in Sisseton, South Dakota.

Advertisement

She set out to visit the Sisseton area and convinced parents that her school, not far from Sisseton, would be a wonderful place for their children to be educated. She soon began bringing children to board at her school, where they were taught English, reading, math and agriculture.

Lynch's intentions were no doubt positive. She believed strongly in the value of education, but she seemed unable to recognize and rise beyond the federal policy of the day regarding Native Americans: Education for Extinction, as the title of the 1995 book by historian David Wallace Adams states. The goal of the system, some say, was the destruction of Native American culture.

One of Lynch's major concerns, Wright said, was the future of Native American girls. She wanted to educate them to a sense of independence so they would not end up being married and dominated by their husbands, whether they were Native American or, worse, white men.

Supporting her schools required fundraising, a skill Lynch had developed well. She was easily able to speak in her letters of her success, enrolling 90-100 students at a time. She also claimed that parents and students were happy with the school, never mentioning the recidivism of students who would go home for holidays and not return. Apparently, as Wright said, there is little in the way of archival records that survived to back up why students did not return.

One of Wright's main challenges in her preliminary research is finding a wide breadth of historical resources as well as an overall lack of resources written by women. However, one of the webinar participants, also a researcher on the topic of Native American schools, noted that she has found women's voices in letters of mothers who wrote to their children in the boarding schools. She also noted that children's letters to parents were usually censored, so parents did not receive full pictures of what was happening to them at school. Mothers also wrote letters to those in charge of the schools, but these were usually left unanswered and, therefore, women's voices were unfortunately silenced.

The movement to censor Native American culture was unfortunately successful, making it difficult to find the silenced stories.

The dormitory of the former Morris Industrial School for Indians now houses the Multi-Ethnic Resource Center at the University of Minnesota Morris. (Wikimedia Commons/McGhiever)

For researchers interested in pursuing the history of Catholic sisters and their work among Native Americans, Wright noted that Marquette University in Wisconsin has one of the best collections of documents about this history. The Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, also has significant resources, she said. Wright also said she had located valuable information at the archives of the University of Minnesota in Morris.

Unfortunately for researchers, most of the information discovered is piecemeal, requiring a great degree of perseverance and time to study and organize.

I felt privileged to participate in Wright's presentation and left grateful that there are researchers seeking to bring these stories to light, but I also felt a deep frustration about how much history has been denied to all of us. When our Presentation Sisters came to the Dakota Territory from Ireland in 1880, the Indigenous people welcomed them and supported them through their first dreadful winter and into spring and beyond until they could make it on their own.

Unfortunately, the sisters left their original area and went further north to work with the pioneers of eastern South Dakota. At the same time, the Native Americans were pushed further west onto reservations. We lost touch with them as a people and, to our loss, never really learned about who they were and are, except for a few of our sisters who did and do work with the families on the reservations.

The lecture and conversations afterward challenged me to ponder the query about how dominant culture seems to trump the Gospel and how I might become better at discerning how this happens in my own daily life.