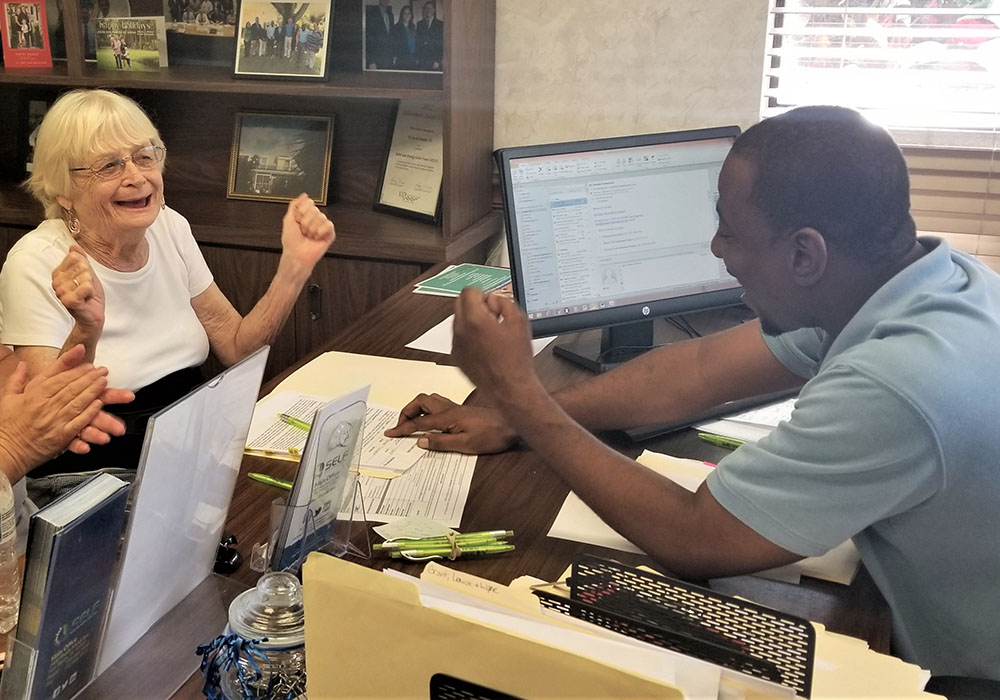

Carolyn, a widow in Florida, reacts to being approved for a microloan from the Solar Energy Loan Fund, one of the funds of the Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati. The loan was going to be used to upgrade her insulation and provide a high efficiency air conditioner. (Photo provided by the Sisters of Charity in Cincinnati)

Depending on their community resources, sisters find ways to give women a hand up in a way that makes them financially independent, whether that's through economic empowerment, donations, education, or even opening a bank window for people who live in poverty.

Panelists described various strategies in their answers to this question:

Women in less-developed countries are using microloans to begin small businesses to support their families and local communities. Can you give examples you have experienced of sisters doing this or share some best practices of such an enterprise?

______

Grace Mary Kenyonga, from Uganda in East Africa, is a member of the Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, the region of South Africa. In South Africa, she first ministered to adults and children with HIV/AIDS and taught high school religious education and catechism. For two and a half years, she served in a predominantly Muslim area in Senegal, where she worked in the community's clinic for the most marginalized and vulnerable in society. She has recently been missioned back to South Africa.

Grace Mary Kenyonga, from Uganda in East Africa, is a member of the Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, the region of South Africa. In South Africa, she first ministered to adults and children with HIV/AIDS and taught high school religious education and catechism. For two and a half years, she served in a predominantly Muslim area in Senegal, where she worked in the community's clinic for the most marginalized and vulnerable in society. She has recently been missioned back to South Africa.

I am familiar with ways microloans have empowered women in the remotest areas of Uganda. Small amounts of money or equipment given to individuals or women's groups can help create stable home incomes, but banks won't lend such small amounts — especially to women — because of the uncertainty about the clients' ability to repay.

But there are alternatives: Nongovernmental organizations, or NGOs, encourage women to form groups and work together to generate income that can later be used for loans among group members. After training, members begin a project (gardening, handicrafts, livestock farming), and when the products are sold, this becomes the capital of the group, which makes low-interest loans to members. If members lack the finances or equipment needed to begin the project, NGOs may give them a grant to begin with.

The interest accumulated from the loans is kept in a group account, and every time she comes to pay the loan, each member is required to save something in a personal account. Because of the financial uncertainty in most of the homes, payments are made weekly to avoid defaulting. A member can use her personal savings whenever she wants. Group members act as guarantors to each other: At least two must stand for a member before a loan is given. If she does not pay, repayment will be made from the savings or personal projects of the two guarantors. This encourages members to regularly visit and encourage the borrower to be serious about her income-generating activity.

In another alternative, the loans are given directly by the NGO to the group. The members serve as guarantors for each other as described above, but the NGO holds and insures the loan, so if a member dies, the family and the guarantors would not have to pay back the loan. But ordinarily, failure to pay means the NGO might take the guarantors' savings and confiscate their business.

These microloans have improved the lives of women.

- Women are empowered by having their own finances. Rural women with no formal employment had no personal income. All money belonged to the husband, and women did not have much influence in family finances. Many women had never had a bank account and did not have necessary documents like land titles.

- With their own finances, women can make decisions in the home. They can improve their living conditions without having to wait for the husband to provide it. They can educate their children, especially the girls.

- I've heard many stories about women who lost their babies because they had no transport to health facilities if their husband was away. Now, women can use their savings in emergencies.

- Microloans have increased women's self-esteem. Although the husband is the head of the household, the group monitoring assures that an abusive husband cannot misuse the money lest his property be confiscated, and the woman is more likely to participate.

- In the group meetings, women learn financial skills like bookkeeping and financial management.

Dawn Nothwehr is a Franciscan Sister of Rochester, Minnesota. She has taught religious studies at several universities in the Midwest and since 1999 has held academic appointments at the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, where she currently holds an endowed chair in Catholic theological ethics in the Department of Historical and Doctrinal Studies. She is a prolific writer and speaker, publishing in peer-reviewed journals, blogs, book reviews, online posts and media.

Dawn Nothwehr is a Franciscan Sister of Rochester, Minnesota. She has taught religious studies at several universities in the Midwest and since 1999 has held academic appointments at the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, where she currently holds an endowed chair in Catholic theological ethics in the Department of Historical and Doctrinal Studies. She is a prolific writer and speaker, publishing in peer-reviewed journals, blogs, book reviews, online posts and media.

The Sisters of St. Francis of Rochester, Minnesota, have a long tradition dating back to our foundation in 1877 of giving people "a hand up," not only "a handout." In providing the highest-quality health care and education to ordinary small townsfolk and farmers of southern Minnesota, the sisters did what their faith and culture had formed them to do: Neighbors always helped neighbors through hard times with small loans and/or personal service.

Thus, the basic ethos and "business model" of microfinance was nothing new to "Mother Al's Gals," an affectionate nickname for the religious daughters of our foundress, Mother Mary Alfred Moes. As our ministries expanded across the globe, our "hand up" activities followed, but often, the needs required expertise we did not have, so we found trustworthy means to meet those needs.

As we were able, we have made loans to various groups. From 1993 to 2018, we provided a larger loan to Accion, a global nonprofit with a mission to advance financial inclusion by giving people the financial tools to improve their lives. Founded as a community development initiative serving the poor in Venezuela, Accion is known as a pioneer in the fields of microfinance and fintech impact investing.

When we sold or transferred a couple of our ministries, we used the money to establish the Franciscan Fund, and from it, we have made grants to organizations or individuals in need. It is a way of continuing our ministry through our finances. In the early years of the fund, we were able to give large amounts to fund institutional-sized projects each year. For example, since before 2005, we've made annual donations to FINCA International. According to its website:

"FINCA International is the founder and majority-owner of 20 community-based microfinance institutions and banks across Africa, Eurasia, Latin America, the Middle East and South Asia, Through this global network, called FINCA Impact Finance, we are meeting the needs of previously unbanked clients. FINCA does so by providing access to financial services and enabling full participation in the economy for the world's poor.

FINCA takes an innovative approach to microfinance, combining traditional branches with agency banking, alternative credit scoring and analytics, mobile wallets, point-of-service biometrics and the use of tablets. Together, these technologies help us reach and serve more clients in remote areas."

Today, the grants are smaller and more often given to direct needs, including disaster relief. Currently, our efforts toward microfinance or the needs of women are through our investment in programs like the Climate Solutions Fund or KKR Global Impact Fund. They are not primarily or only microfinance or women's issue investments, but have components that do address both of these issues. By partnering with these larger funds, we hope to utilize their expertise and global connections to maximize the impact of our dollars.

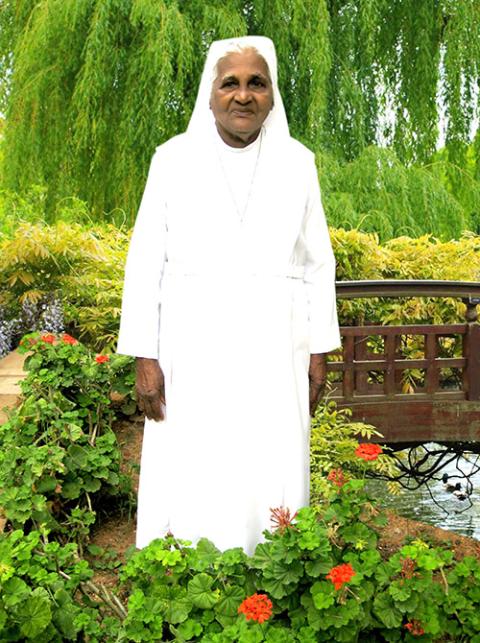

Salesian Sr. Nancy Pereira, the founder and director of FIDES (Family Integral Development and Education Scheme) (Provided photo from Salesian Sisters)

Teresa Joseph is a Salesian Sister in Mumbai, India. With extensive academic work from universities in Rome, she has taught university courses, held diocesan and congregational offices, revised catechetical texts, and launched many creative programs for teachers, parents and students. Currently, she is animator of the community at Auxilium Convent, Lonavala. She takes every opportunity to work with children who live in the streets.

Teresa Joseph is a Salesian Sister in Mumbai, India. With extensive academic work from universities in Rome, she has taught university courses, held diocesan and congregational offices, revised catechetical texts, and launched many creative programs for teachers, parents and students. Currently, she is animator of the community at Auxilium Convent, Lonavala. She takes every opportunity to work with children who live in the streets.

Sr. Nancy Pereira (Aug. 14, 1923-July 14, 2010) — a simple, humble and determined Salesian Sister, the founder and director of FIDES (Family Integral Development and Education Scheme) — is a household name in the miserable slum of Ulsoor in Karnataka, India.

A woman testifies: "We were like worms. Sister Nancy came and cleaned our wounds. It is because of her we have this standard of living. My mom was a domestic servant, and I lost my dad when young. Today, I have a very good job."

As an aspirant, I had the joy of working with her. A person of few words and sharp intelligence, she tried to make each one responsible for themselves and others. The "Sister Banker" implemented the model of Muhammad Yunus, Nobel Peace Prize-winning founder of the Grameen Bank.

In 1993, Sister Nancy began FIDES for the development of families, opening a bank window called "Fund for the Poor," modeled on Yunus' micro-giving, saving, and small credit. In the villages, she offered credit to families, especially the women. Among other projects, we witnessed the birth of two cooperatives, two bakeries, two printing houses, a restaurant and several small factories. She saw to hygiene, health, nutrition and care of newborns. FIDES was a person-centered project of the integral education of the family that involved every member.

To get credit, clients informed FIDES, first demonstrating that they had regularly saved small amounts of money for a year, then they participated in the meetings of the group that manages the credits for minimum interest.

Sr. Nancy Pereira

Sister Nancy would often say that work and education are the two ways to conquer misery. Within eight years of loving ministry in Bangalore, she was able to ensure 3,000 families two meals per day. Children began attending schools, the women were working, and alcoholism was greatly reduced.

I often picture that tall, calm and determined figure of Sister Nancy. It wasn't difficult to grasp the secret of her effectiveness. With her feet steady on the ground among the poor and with her whole being immersed in the Lord through constant prayer, she knew how to strike the balance.

She received several international awards, and on Dec. 27, 2000, the central telephone line became incandescent at the Salesian Sisters' motherhouse in Rome, after people viewed a documentary about the FIDES project. The sisters had to answer calls on 15 other extension lines, and the inundation continued for more than a week, from dawn to dusk, with everyone wanting to know how they could send Sister Nancy their donations.

But hers was a firm "no" to a simple philanthropical approach, and a loud "yes" to economical and productive strategies, provided people were open to change their way of thinking and to commit themselves to productive tasks.

Among the titles that sparkled through the media at her death was that of St. John Paul II, who defined her as an indefatigable entrepreneur of the poor.

Today, Sr. Celine Jacob, the provincial of the Salesian Sisters (Daughters of Mary, Help of Christians, or FMA) of Bangalore and her team ensure that Sister Nancy's mission among the slum-dwellers continues. They are studying the spirituality of social work and will host symposiums to make Nancy and her work known. The mission continues!

Mary Ann Flannery is a Sister of Charity of Cincinnati who has held teaching and administrative positions at several colleges. Before her community, Vincentian Sisters of Charity, merged with the Sisters of Charity, she served as community president and in other leadership roles. She has been a freelance journalist, the director of a Jesuit retreat house, and active in social justice issues for more than 30 years. She continues to offer retreats and spiritual direction.

Mary Ann Flannery is a Sister of Charity of Cincinnati who has held teaching and administrative positions at several colleges. Before her community, Vincentian Sisters of Charity, merged with the Sisters of Charity, she served as community president and in other leadership roles. She has been a freelance journalist, the director of a Jesuit retreat house, and active in social justice issues for more than 30 years. She continues to offer retreats and spiritual direction.

It is said in my community that the diminutive but powerful financial genius Sr. Elise Halloran read the Wall Street Journal every day after she had prayed the Divine Office and attended Mass. The Wall Street Journal came in third!

Undoubtedly, Sister Elise's judicious planning got us through the Depression and World War II. It stabilized our hospitals well before government health plans argued to do the same. In 1979, our president, Sr. Assunta Stang, was able to appeal to the community chapter to establish a fund for the purpose of providing "loans and investments to community-based organizations that may not qualify for conventional financing," according to our congregation's website. The fund was approved and named after Elizabeth Ann Seton, the American-born saint and foundress of the Sisters of Charity.

According to an article by Dee Walsh, "Nun Funds: The Original Impact Investors," the Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati "dedicated a portion of the congregation's unrestricted funds for loans to organizations committed to helping economically disadvantaged people develop themselves and their communities." This approach to assisting others has become the ministerial replacement for the droves of sisters once available to do the hands-on service. It is entirely mission-centered.

El Buen Socio is a microlending nonprofit that helps small businesses in Latin America. The group in the picture is the very first funded that is located completely outside the U.S. These honey farmers from Chiapas, Mexico, were able to finance their harvest this season because of a Seton Enablement Fund loan. (Photo provided by Sisters of Charity in Cincinnati)

The Seton Enablement Fund considers projects of nonprofit organizations from all over the world, including low-income housing developments, co-ops and land trusts, business ventures that benefit low-income communities, employment opportunities for worker-owned or minority enterprises, and environmental and sustainability projects. Usually, loans are made for five years at 3% interest. Loans are not made to individuals.

Sr. Pat Wittberg, administrative director of the fund, excitedly told me that in 2018, we assisted organizations throughout the United States, Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. From the initial investment of $4 million, she said that today, the fund is at $8 million with 389 loans totaling $28,837,500, the majority of funds supporting affordable housing.

There are very creative enterprises, like the small business in Indianapolis that hires ex-prisoners to disassemble used technical equipment and save the parts for repairs of broken equipment. Or the loan to honey producers in Mexico, assuring that their honey won't be sold to middlemen at below-market prices, but rather to commercial allies who promote fair trade. And the low interest loan to African Sun Consulting, for growing technology businesses in Zambia faced with otherwise unaffordable 20 to 30% interest rates to finance these businesses.

Testimonies poured in last year, acknowledging the 40th anniversary of the Seton Enablement Fund and celebrating its loans, from covering cellphones and goatherds for poor farmers in Africa to the creation and preservation of $6.6 million of affordable housing in the United States.

Sister Pat added that many smaller religious communities with more limited funds share their resources for the same purposes. They contribute to what is called the Religious Communities Impact Fund, or RCIF, an aggregate of resources founded in 2008.

"We are all facing the same challenges and yet we know we can help fund the mission when we pull together," she says.

Funding from the Seton Enablement Fund helps the Renaissance Community Loan Fund to provide much-needed funding for meaningful small businesses such as Carricka Thomas’ NP Family Medical Clinic, whose mission is to serve the medical needs of the underserved people in her low-income community. (Provided photo from the Sisters of Charity in Cincinnati)

Marie Vianney Bilgrien is a School Sister of Notre Dame living in El Paso, Texas. She taught grade school in Wisconsin and Mississippi and served in Bolivia as a catechist and the director of an orphanage. She directed Hispanic ministry in an Oregon diocese and worked in higher education in El Paso and Shreveport, Louisiana. After she received a Doctor of Sacred Theology degree from the Angelicum in Rome, she began work with the Graduate Theological Foundation and the University of Texas at El Paso.

Marie Vianney Bilgrien is a School Sister of Notre Dame living in El Paso, Texas. She taught grade school in Wisconsin and Mississippi and served in Bolivia as a catechist and the director of an orphanage. She directed Hispanic ministry in an Oregon diocese and worked in higher education in El Paso and Shreveport, Louisiana. After she received a Doctor of Sacred Theology degree from the Angelicum in Rome, she began work with the Graduate Theological Foundation and the University of Texas at El Paso.

Many religious communities donate to Heifer International, an organization that gives animals to poor farmers. Heifer also provides support for women's groups, training in gender equality, and sending girls to school. Heifer notes on its website that "when women have control over their own income, the health, education and nutrition of entire families benefit." The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization says that if women in rural areas had the same access to land, technology, financial services, education and markets as men, agricultural production could be increased and the number of hungry people could be reduced by up to 150 million.

According to The New York Times, during the Bangladesh famine of 1974, Muhammad Yunus loaned the equivalent of $27 to a woman and her neighbors, to make items that they could sell. He believed that making such loans would stimulate business and reduce rural poverty in Bangladesh.

Later, he studied how to design a credit system that would provide banking loans to rural poor. Out of that grew the Grameen Bank in 1983, which national legislation passed so that it could operate as an independent bank. By 2011, the bank had about 8.4 million customers, 97% of them women. The bank learned to trust women to repay the loans because the women worked harder so they could feed their children. [Editor's note: See the essay on Sr. Nancy Pereira above.]

In 2006, Yunus and the Grameen Bank received the Nobel Peace Prize. His model has been imitated by many organizations around the world, including the United States. It has also expanded to work with groups, such as families and relatives, community projects, and groups who form a business.

For example, the U.S. nonprofit Kiva has loaned out $1.4 billion to 1.8 million lenders in 77 countries. At NerdWallet, Ben Pimentel reported on "13 top U.S. nonprofit lenders." According to Pimentel, Accion New Mexico gives out "loans from $1,000 to $1 million" to small businesses "in New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, Nevada and Texas"; they also offer "business counseling and marketing support." Pimentel also cited Justine Petersen in St. Louis, which offers loans to small businesses "typically of less than $10,000." Another highlighted microlender, LiftFund, based in San Antonio, loans money that borrowers use "to buy equipment and supplies."

I was surprised that there is quite a bit of negative criticism on the internet. I suspect that some people are against lending mainly to women; others may be opposed to lending to groups because it may emphasize other problems, i.e., lack of water, lack of education, lack of needed resources, electricity, shelter. It seems to me that we should work with other organizations to solve those problems.

If big problems paralyze us, then let's do something else that helps the poor. One of my friends has a religious sister friend working in India, and asked what her Altar Society group could do to help. The sister in India asked the women she works with what they would like; they said seeds. That first year, the Altar Society sent $100 worth of seeds. What a simple, great beginning that is bringing to a small area of India!

Advertisement