(Julie Lonneman)

"Hristos a înviat! Adevărat a înviat!"

For those whose Romanian is a little rusty, that's translated "Christ is risen! Indeed, he is risen!" This is the dialogue with which Romanian Greek Catholics greet one another throughout the Easter season. (It's actually the greeting for all who share the Orthodox tradition — each in their own language.)

When I first heard it, it seemed a lovely piety, something like my Irish ancestors might have said in their day. I also knew that when in Romania, I should do as the Romanians, and try to greet or respond appropriately whenever it was called for. That was years ago. Of late, the greeting has come to mean a great deal more to me.

In the past few years, I have been reading diverse reflections about the resurrection. In particular, I have been trying to grapple with what some theologians call the "eschatological imagination," that is, a worldview that springs from the resurrection. I will not try here to summarize all that thought, but rather share some simple reflections about what it might mean for the Easter happening to permeate our consciousness.

I know this sounds pretty elementary. After all, if we didn't have Easter and believe in the resurrection, we wouldn't be Christians. We wouldn't count the saints as a part of our lives; we would mourn death as our tragic, inescapable fate and the mockery of all human achievement. If we didn't believe in eternal life, our sense of unassailable human dignity would undergo a revision; our moral system would need to be rethought, and the best we might hope for would be the ethics of the great existentialists — some of whom ended their days with suicide. The questions I want to explore are: at what level does the resurrection inhabit the depths of our consciousness, and what difference does it make?

Graphic Good Fridays

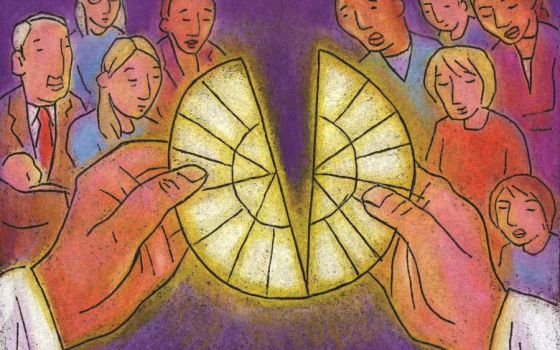

Someone suggested that I reflect on Easter using my experience in rural Peru, where I had the privilege to live among people who were economically very poor. My first response to that was to think that the folks I knew and prayed with were Good Friday Catholics. Their images were graphic: bloodied crucifixes; Jesus, the "Just Judge," being flogged; the Pieta; Jesus laid out in a glass-sided coffin, etc. Good Friday processions were passionate, elaborate and long. Easter seemed to be a secondary celebration after the main event. Peruvian theologians explained that this approach was really an expression of a deeply incarnational faith. The people understood that the Son of God was truly one of them: one who suffered physical pain and humiliation. Like them, Jesus experienced ongoing injustice. With Mary, they had too often shared the sorrow of a mother whose children die out of season. Like the disciples, they had mourned the murder of well-loved and promising young people and leaders for whom they had hoped for so much. The crucified Christ was one of them.

The best we had there of an Easter celebration was a dawn procession in which an image of Christ was carried from one church and an image of the Blessed Virgin from another. The processions moved solemnly toward a central point until they were in sight of one another, and then everybody sprinted for the joyful first encounter of the risen Lord with his Mother. It was delightful — and sparsely attended. Yes, these people believed in the resurrection and heaven, but their visceral sense of Jesus' identification with them came through his sharing the sufferings of their life and giving them meaning.

Seeds and new life

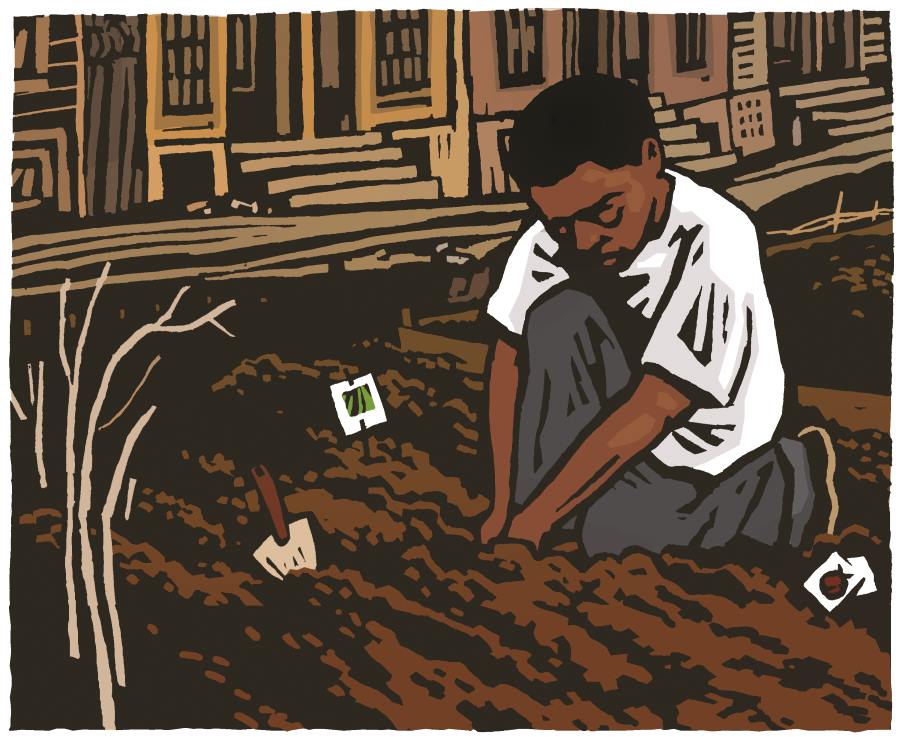

The cover of this issue of Celebration depicts a child in an urban setting seeding a tiny plot of earth. In the midst of a concrete universe, he's doing his best to foster a life and growth that don't seem "natural" to his environment. And maybe that's the point: The child has not learned to settle for what's "natural," or for "reasonable expectations." The first thing I thought of when I looked at our little cover guy was my mom's favorite children's story, "The Carrot Seed." For those who don't know it, it's the tale of a little boy who planted a carrot seed. His mother gently suggested that it might not grow, his father warned him not to be disappointed, and his big brother taunted him, repeating that nothing at all would come of it. But still the little boy watered, weeded and watched, day in and day out. Ours was the musical version of the story (45 rpm), and I can still sing the child's proclamation of faith that "Carrots grow from carrot seeds!" That little boy was tender with the soil and hoped against hope. Finally, nature, water, the earth and his efforts brought forth the biggest carrot any of them had ever seen. "Carrots grow from carrot seeds!"

As far as Easter is concerned, our cover boy and "The Carrot Seed" are pretty good parables. They can be seen as children's commentaries on Jesus' teaching about seeds and new life. The seed must die before it gives new life; the buried seed grows as it will, without the planter's understanding or control; the seed can even produce a hundredfold. All of that expresses the mystery of existence, the Creator's sacramental gift of life to us. We might say that it expresses the hopeful "ordinariness" or the "naturalness" of our faith. As Robert Browning wrote in "Pippa's Song":

The year's at the spring,

And day's at the morn;

Morning's at seven;

The hillside's dew-pearled;

The lark's on the wing,

The snail's on the thorn;

God's in His heaven —

All's right with the world!

But, if that were all, if the seed and nature told the whole story, what need would we have for Christ's passion and resurrection? Isn't it, at least for those who have eyes to see, all already written into the story of the universe?

Beyond the natural

Asking that brings me back to the "eschatological imagination," a highfalutin phrase that tries to describe a way of understanding the world that goes beyond everything we think of as "natural." In terms that might be more familiar to us, I believe that the resurrection invites us to a transformed understanding of life. Surely, the seed dies and gives forth a hundredfold — if, as the little boy knew, it is planted in good soil and tended with care. That's God's "Plan A" for the world. It asks for the faith and hope that allow us to accept the risk of growth. But, what of the world where an enemy has sown the field with salt, where some have usurped ownership of the seeds, when global climate change has chilled spring? In a word, what happens when sin exercises a seemingly omnipotent reign?

That was the disciples' question on Easter morn. They had heard Jesus preach about seeds and the kingdom, they had seen him raise the dead, and then they experienced his brutal death. The tomb proved the power of destruction over the power Jesus had proclaimed. As Anthony J. Kelly writes in The Resurrection Effect: "For the powers of the world … the tombs of those who challenged them are signs of their power to impose an unquestionable rule" (The Resurrection Effect: Transforming Christian Life and Thought, Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis, 2008, p. 142). The disciples were left with a seed that had rotted instead of germinating; their hope had been bloodied and buried. Perverted human nature, exercising its most destructive power, had proven to be the final, victorious author of history.

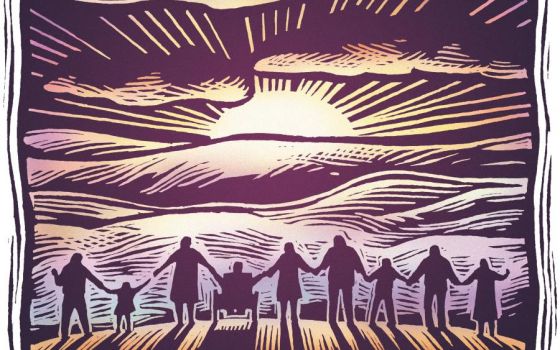

That was the scene on which the risen Jesus appeared. There was nothing natural about his new presence with those whom he loved. His encounter with his disciples left them thoroughly disoriented and quite rightfully terrified. More than the appearance of a ghost — something they could at least imagine — Jesus' presence among them overturned reality. Jesus' resurrection annulled everything they knew to be normal and natural. It was the sudden, amazing revelation of what he had tried to teach in so many ways: He had freely accepted death in order to unmask it publicly. He had clearly said, "I will lay down my life for my sheep … I lay down my life in order to take it up again" (John 10:15,17), and yet they had no context from which to understand that. Nothing Jesus did could prepare them for what they had to experience for themselves. The resurrection had to, in the words Luke gives to Zechariah, surprise them like a dawn from on high — a dawn that eclipsed all others. Everything that had been certain was changed because death itself was not definitive, and therefore sin had no power and every threat was eviscerated.

Hope expressed as patience

British theologian James Alison says that in in the light of the resurrection, the virtue of hope is transformed into patience. It's quite an astonishing claim! This implies that, for those who believe, hope is no longer necessary because salvation is sure, even if slow to be revealed. Christian faith, then, is not the hope-filled belief that God will rescue us, or that tragedies of the past will be obliterated, but that reality itself is thoroughly different from what it appears to be because God is working in and through it in ways often beyond our comprehension.

That belief gives birth to a transformed faith and love of God. We might envision that new expression of faith through contemplating Mary at Cana. When there was no wine, the symbol of covenant love, she did not make a petition, but humbly described the reality to Jesus. With neither demands nor commands, she simply told the others, "Do whatever he tells you." This is hope expressed as patience: knowing neither when nor how, but certain that reality would be transformed. Mary showed us how to wait on God's providence, more certain than the dawn. In response, Jesus implied that her expectations were unrealistic — and that might well be the point. Once we are in the realm of Resurrection faith, realism loses its luster and we abandon our myths about things being under our control.

This is what I think the Good Friday processions were about. They were expressions of clear-eyed realism and the supra-reasonable expectations that can only be born from powerlessness. The people carrying the image of Jesus' body were processing with and for God the Father. They did not represent Joseph of Arimathea and the women who accepted Jesus' death and cared for his corpse. They were far from being like the disciples who ran from the reality and the danger of the situation. The people carrying the crucified Lord through their town were expressing their solidarity with God's loss, and giving sacramental expression to their faith that God was with them in their own losses. The people who carried the image of Jesus recognized their loved ones in his face, and they knew that the Father does the same. Although all evidence is to the contrary, they believe that somehow sin and death have been overcome and that God is working in their midst in hidden and powerful ways.

Advertisement

Hidden ways

When, in the midst of suffering and evil, people believe that God is working in powerful though hidden ways, their faith and their love of God have reached a new height. When people can be patient with God's ways, they have purified their love and accepted a faith that exceeds their highest hopes; they no longer worship a god of their own desires, but have opened themselves to God's unimaginable future. That sort of faith is a grace that changes everything.

In my experience, it is that sort of faith that leads people to see miracles in any and every moment of life. This is no glib or sweet, naive religiosity. It is, rather, the privilege of the poor. When people have come to faith in God's presence in the worst, most hopeless, ever-dead-ending circumstances, then every other moment is also a clear expression of that same miraculous presence. Every birth, every sunrise, every fertile carrot seed reflects the One who gives life in abundance.

A transformed perception

People who have come to this sort of faith no longer understand the resurrection through the sign of the seed. Rather, because they believe in the resurrection, the seed and everything else gets interpreted in its light. Because they believe in the resurrection, they know that evil and injustice do not have the last word — even here and now. They can relate to others out of the deep understanding that every enmity will be healed, and thus, even in the present moment, enmity itself is nothing more than a false perception. They can live out of a patient love of God that rejoices in the faith that God's imagination is vaster and far more loving and creative than our own. If they can't fully agree with Browning's poem, it's because they no longer separate heaven and earth and would therefore rather say, "God's right, right here, with the world." That is, I believe, the eschatological imagination: a transformed perception that seeks the meaning of absolutely everything in the light of the resurrection of our crucified Lord.

Many of the Romanians who proclaim "Hristos a înviat!" are people who suffered under 50 years of Communist dictatorship, whose bishops and fellow church members were imprisoned, tortured and martyred. They had risked their own liberty to celebrate the sacraments in the underground church. That experience forged in them a unique sense of the profound meaning of Easter faith. They, the poor, and all who bring faith to their own suffering give living witness to Resurrection faith.

Easter is dawning upon us. Christ is indeed risen! Let us ask for the grace to perceive and proclaim it with our lives.

Editor's note: This reflection was originally published in the April 2014 issue of Celebration. Sign up to receive daily Easter reflections.