(Julie Lonneman)

In 1959, Pope John XXIII was already describing the council he convened as a "new Pentecost." The Holy Spirit was pouring out charisms to reinvigorate the church, its mission in the world, and its outreach to other Christian communions and religions. Our annual liturgical celebration of Pentecost echoes this same theme by occasioning what the council called ressourcement, a reaching back down the historical lifeline to the original event and inspiration that created the church.

A great harvest

As our birthday celebration, Pentecost offers us a rich harvest of biblical themes. It is named for being 50 days from Passover in the Jewish liturgical calendar. Passover, or Shavuot, celebrates the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai and the community's joy at harvest time, the surest sign of God's blessing in the promised land. Food security is tied to Israel's commitment to the Mosaic commands in Deuteronomy governing harvest; firstfruits; gleaning; and care of the poor, widows, orphans and alien residents; as well as the practice of redistribution and debt forgiveness every seven years and in the 50th year — the Jubilee year. The message was clear: As God has saved and loved his people, so they must extend those same blessings to others. Both the Exodus and the Exile are remembered, captured beautifully in Psalm 126: "When from our exile God takes us home again, we'll think we are dreaming. Those who go out weeping, carrying seed for the sowing, return rejoicing, carrying their sheaves."For Jesus, the kingdom of God is seen as a great harvest, the fields white with grain, wanting only laborers to gather it in (Matt 9:37). The parables of the sower, the wheat and the weeds, the vineyard, the fig tree, the single grain of wheat that multiplies by dying, and other metaphors place Jesus' vision within the covenant promise of a messianic age. He is in the world as food and drink to hungry people. The evangelists see his death as the grain of wheat sown at Passover, springing green again in resurrection and producing the harvest of Pentecost.

Renewing the liturgy

But there is more to the story than just theology and spiritual imagery. Scholars who have recreated the historical conditions at the time the Gospels were written suggest that Jesus' frequent references to farming, food and meals were grounded in real-life conditions of hunger brought about by weather and economic policy. Palestine was occupied by the Romans, who used their military might to extract wealth from the land, and labor and loyalty from their subjects in the form of taxes and produce. Jewish grain, oil and wine went to Rome, often leaving the local population with subsistence diets, a condition that served as a form of control. The dream of abundant harvests, surplus grain, feasting and food security underlies many of Jesus' parables. His power to multiply food in the wilderness was a threat to Roman control and to the temple authorities who controlled the religious festivals surrounding harvest and animal sacrifice. Jesus' cleansing of the temple struck at the nerve of complicity between Roman and religious interests. The Gospel renewed Jewish liturgy, from Passover to Pentecost, to reflect God's Exodus covenant, including the call to justice.

Pope John's prayer for Vatican II contained all of these themes, including the need to renew the liturgy to make visible the participation of all the baptized in the Paschal Mystery, the extension of God's harvest of mercy in the world and, in particular, to the poor. Fifty years after Vatican II — a Jubilee year — we are reminded that this core catechesis will renew the church and her mission, but only if we move it from language, ritual and symbol to embodied activity in the world. The first Pentecost was experienced as an outpouring of wind and fire, good news delivered in every language, reversing the curse of Babel that had thwarted universal unity. Our new Pentecost calls the church into the same expansive and generous spirit of sharing the Gospel with the whole world.

Ritual and food security

For us today, the rich theme of harvest invites us to reconnect our liturgical ritual to the reality of food security. The ancient world held its breath each spring as sowers went out to commit precious seed grain to the ground and the weather, knowing that crop failure meant almost certain famine.

Modern people, insulated by supermarkets and cheap food from the realities of agriculture, easily ignore the fact that global food reserves are being impacted by climate change and rising demand. A quick search of the Internet reveals that stockpiles are at their lowest levels in 40 years, with the global population consuming more than it produced in six of the past 11 years.

Competition over food is hitting the most vulnerable regions of the world first, pushing an estimated 44 million people into crisis in 2012, undermining political stability in parts of the Arab world. Experts warn that we are reaching a tipping point in food security, and that global weather conditions this year will be critical.

By May 2013, we will know whether drought and flood predictions have sounded the alarm. For most Americans, this may only mean a rise in food prices, but for much of the world, actual shortages will hurt health and nutrition for millions if not billions of people. Every other issue, from armed conflict, to migration, to market instability, to national decisions to strengthen strategic reserves, will be drawn into this most basic of all challenges.

Perhaps one curious sign of still-unconscious public anxiety over food in developed countries has been a paradoxical surge in extravagant consumption of specialty foods, and adulation of chefs and cooking shows. Besides the enormous waste of food in our culture, what message does a permissive display of eating and drinking, or the news that obesity is a major health threat in the United States, say to the rest of the world? Are we prepared to help and inspire others in a time of crisis?

The church's role

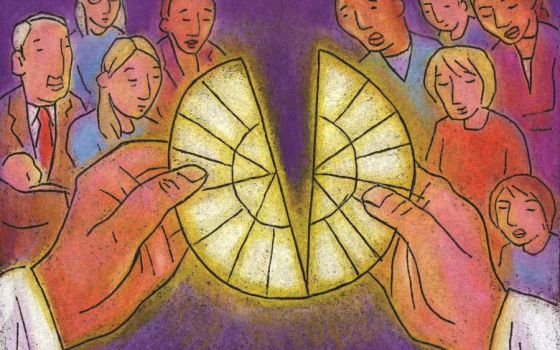

Many religions, including Christianity, place food at the center of their worship. We gather at the table of the Lord, where bread and wine become our encounter with God and one another. Spiritual and physical hungers are met by God's promise of abundant life for all. Our churches open their doors to welcome friends and strangers into one community. The center we share is both the altar of personal sacrifice and the table of justice that compels us into the world to advocate for the hungry poor. If we are true to our own message, how churches publicly address the question of the universal human right to eat will test our values and beliefs to the core.

Advertisement

Strategies

Crisis management requires careful planning, priorities and strategies based on good information. The church's role requires no less attention to food insufficiency in the parish or neighborhood. Existing networks of pantries, kitchens and distribution systems like Harvesters, the Catholic Worker and Catholic Charities are a sign of faith in action. Important voices that have long advocated changes in our food system are gaining prophetic prominence as crisis pushes food security to the top of media coverage. Advocates for regional markets, crop diversity and corporate decentralization, rotation and conservation, less petrol- and pesticide-based production, more community and home gardens, better education to reconnect urban people to the sources of their food — have been grounded in the biblical truths about creation, stewardship, justice and the common good.

Parishes can do ordinary things to raise awareness of how ritual and reality connect, or how interdependent our lifestyle and eating choices are to the survival of others. Eating is a communal act. What happens on our altars and family tables touches the lives of millions of people around the world. How can our eating heighten our sense of responsibility for the earth we share with 7 billion other human beings?

A parish garden or purchasing food for church and school meals at farmers' markets supports local producers and can save money. Using the idea of seasonal eating and the 100-mile diet teaches people about the high costs and carbon footprints that are incurred when we insist on having every kind of food all year round. Offertory processions with children carrying up items to stock food banks and meal programs is powerful catechesis that creates solidarity with hungry neighbors. Buying Fair Trade coffee and other products supports just markets and sends a signal to those who exploit the poor in other countries.

Abundant life

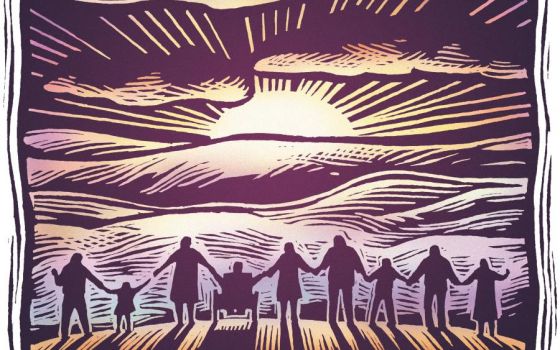

The new harvest John XXIII envisioned for the church 50 years ago is ripe for implementation in our attitudes and activities, ritual and real. The solution to world food security is less likely to be competition over scarce resources if we can seize the challenge to change the way current systems waste, hoard and distribute food to protect disparity, a vexing reality addressed in papal encyclicals from John's Mater et Magister down to current letters by Benedict on global economic reform.

The harvest is great, but the laborers are few. Let us pray the Lord of the Harvest will send each of us to proclaim God's desire for abundant life for all God's children in our world.

Editor's note: This reflection was originally published in the May 2013 issue of Celebration. Sign up to receive daily Easter reflections.