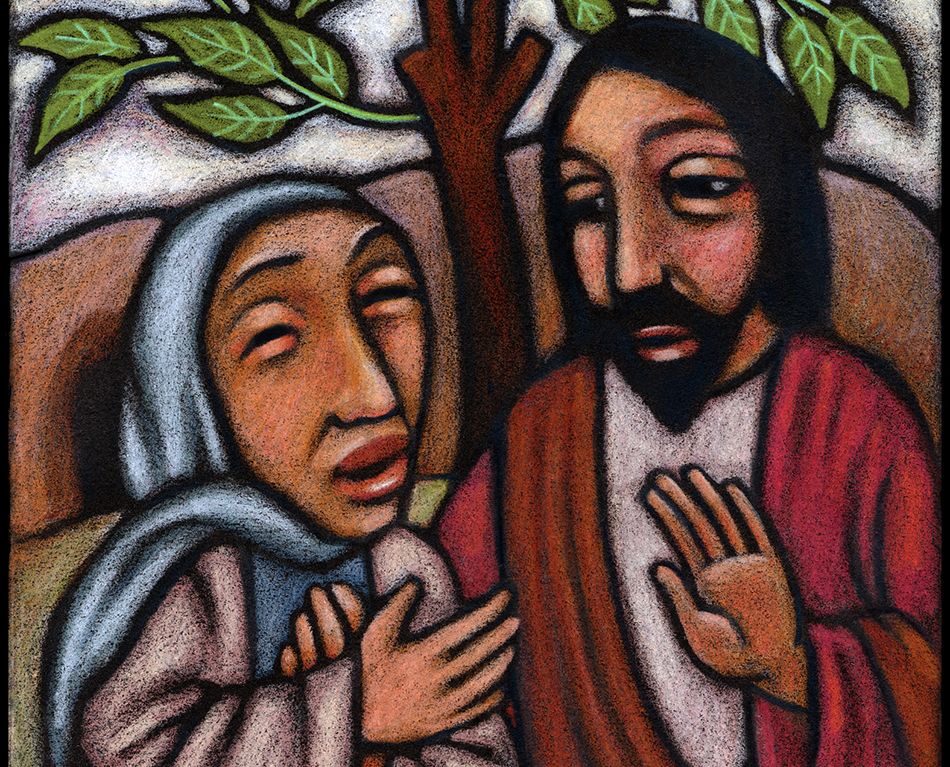

(Julie Lonneman)

When I was in the eighth grade, I went to my first funeral: my grandfather Tom's. That was 70 years ago, and at the time a funeral Mass always included an ancient hymn called the Dies Irae. I remember reading the translation of the Latin words in my missal and being appalled at the fearsome depiction of Judgment Day it presented. I could not imagine what "that day of wrath, that dreadful day" had to do with my kind and gentle Gramps.

Thanks to the Vatican II reforms, the funeral rite no longer focuses on God's severe judgment. Black vestments have given way to white, and the stated purpose of the revised rite is "to bring hope and consolation to the living through faith in Christ's resurrection and God's mercy." In other words, the funeral is now an expression of the faith we celebrate all through the Easter season.

There is indeed consolation in the belief that death does not get the last word. But that belief does not release us completely from the mourning that follows the death of someone we love. Grief can be described as a journey toward healing and acceptance, and its path is long and hard and painful. It twists through the mists of disbelief and the storms of anger; it dips into the deep valleys of depression and winds through the torturous of paths of pain and guilt. Our celebration of the Easter season needs to address not only the hope of bereaved believers, but also the difficult time they are going through. And the Easter season is rich with opportunities to do so.

Rejoicing in God's will

All too often, Christians offer some pretty cold comfort to survivors. I think of a woman whose friends assured her that her dead baby was now an angel watching over her from heaven. She would much rather have had him safe in his crib! My grandmother's first baby died a few weeks after her birth, and her husband's pastor told her the same thing — but that proved a lot better than her parents' stern pastor scolding her for her refusal to accept God's will.

The Easter season triumphantly refutes that grim view of God's will. Our alleluias resound with the conviction that God's will for us is abundantly joyful life — not only after our death, but also here and now.

Releasing the bonds

Jesus wept when he went to Lazarus' grave. But then he dried his tears and did something that left the onlookers gasping: He called the dead man out of the tomb.

In keeping with Jewish burial customs, the corpse was wrapped in linen bands into which aromatic spices were tucked. "Unbind him and let him go," Jesus told the stunned observers (John 11:44). He also wants to see us freed from the bonds of grief. Those bonds are not made of linen, but spun from various strong emotional fibers.

The bonds of disbelief are the first ones people struggle with in the wake of any painful loss. "How could this have happened?" they ask over and over again. The newly bereaved frequently catch themselves forgetting that someone is dead. They can't wait to tell something to the person who can no longer hear them; they sense a loved one's presence in the next room or follow a stranger who seems wonderfully familiar down the street.

There is some comfort in this amnesia, for remembering hurts — so much so that people sometimes throw themselves into work or seek chemical relief to keep from remembering. But letting the reality of the loss sink into one's consciousness is the only way to begin to deal with it and start to rebuild a life without some key person. "You will know the truth and the truth will make you free," Jesus once said (John 8:32), and that is especially true for the grieving.

The bonds of pain are persistent. It helps to remember that the risen Jesus, though now beyond pain, still bears scars. In the first Easter season, he had to display his wounds in order to identify himself to his friends. The paschal candle that burns in our midst is marked with five red nails that signify the wounds in Jesus' hands, feet and side. He has known suffering and death, and he has not forgotten them.

Jesus knows loss as personally as any of us. Like every human infant, he learned its meaning the minute he left the only warm and sheltering home he had ever known and drew his first breath. His lungs inflated with some cold and alien substance, which he promptly expelled with a wail of protest.

None of us remembers the pain of that moment now. Yet when we were still new, we did not quickly forget our terrifying journey through the birth canal. If you have ever tried to slip a garment over a tiny infant's head, recall how the little one struggled and screamed.

Look back over Jesus' life on earth. Tradition has it that Joseph died in the arms of the son he had nurtured so lovingly. Jesus surely grieved with Mary at the death of this good man under whose tutelage he had learned the art of carpentry and the faith of his ancestors. When Herod had his cousin John the Baptist beheaded, and Jesus heard the news, he withdrew from where he was to "a lonely spot" (see Matt 14:1-13), surely to mourn.

Lazarus and his sisters, Martha and Mary, were dear friends with whom Jesus spent many a happy hour. When he got the news that Lazarus was ill, he insisted that the sickness was not leading to death and put off going to him. When he finally reached his friends' home, Lazarus had already spent four days in the tomb. Both his sisters, just like us, asked where Jesus had been in all this: "If you had been here, my brother would not have died" (John 11:21, 32). And Jesus stood weeping at the place where his dear friend was buried.

He knew bitterer losses as well. As his life on earth neared its end, one member of his closest circle of friends betrayed him; another denied ever having known him. All but one of them fled after his arrest, leaving him to face torture and death without their supportive presence.

Grief is often a lonely affair. A few weeks after the funeral, the thank-you notes are written, the death certificate arrives and the phone stops ringing. The people who provided support go back to the business of their own lives and all too often expect the grieving to get on with theirs. No one seems to understand that these folks' sorrow is not laid to rest with the dead. Rather, they are in constant pain.

Some people turn to support groups. Their major drawback is that they seldom include survivors because people tend to drop out once their own grief has been resolved. Sorrowing people need to be in touch with someone whose own experience offers the assurance that people can and do heal.

Jesus is such a person. And he is close by, no longer bound by the limits of time and space as he was in ancient Israel. The risen Lord has taken up residence within us, just as we dwell in him.

The bonds of anger are bitter. Grieving people's anger can be directed toward many targets: the person they hold responsible for a loved one's death, the unfairness of the situation in which they find themselves, the happiness other people are enjoying. They may even feel angry at the dead person for leaving them, for neglecting health or taking foolish risks. They may even, to their terror, feel angry with God.

Everyone knows we shouldn't get angry. We even rank that emotion among the seven deadly sins. Yet it is a natural reaction to a threat, one we share with all the other animals on this planet.

Feeling angry and nursing anger are, however, two very different things. Because it floods the human body with adrenaline, anger seeks release, but it can find it in strenuous physical activity that is not harmful to anyone.

As for being angry with God, there is ample biblical precedent for that. Job challenged God, saying he wanted to put the deity on trial; Jeremiah complained that he had been very badly used (see Job 23:2-7a; Jeremiah 20:7).

The bonds of guilt are quite like the bonds of anger, except that they are self-inflicted. For guilt feelings rise when we turn our anger on ourselves. Bereaved people torture themselves with the belief that they could have prevented the death or even that they caused it. They berate themselves for all their failures in the relationship. If the death and resurrection of Jesus speak to human failure at all, it is to say that nothing is beyond forgiveness.

The bonds of depression are the heaviest. At some point in grief — or at many points — the sky is always leaden. The smallest things require more effort than a mourner can muster. This is not clinical depression, which comes without cause and requires the care of a psychiatrist, but the depression that is an altogether normal response to loss. Jesus once offered an invitation that is still open: "Come to me, all you who are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest" (Matthew 11:20).

Advertisement

Holding to the promise

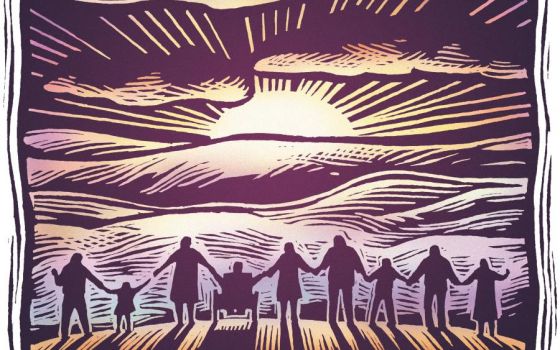

Healing comes slowly, but it does come. "Weeping may linger for the night," the psalmist sang, and the night may indeed be long. "But," the biblical poet adds, "joy comes with the morning" (Psalm 30:5b). We let go and find comfort in knowing that the one who is now with God is also with them because God is.

My grandmother spoke often of the tiny daughter whose death had torn her world apart. I can't remember not knowing about that baby. She remembered lying in her darkened bedroom, Gram told me, while the infant lay on the kitchen table under the doctor's fruitless ministrations. Suddenly she saw a light pass through the room and disappear, and at that moment she knew her child was dead.

Gram lived to a ripe old age. In her twilight years, she descended into dementia, and for a long time she could no longer speak coherently but only babbled like a baby. But as she was dying she looked at the wall and said very clearly, "Look, there's Tom and he's holding the baby!" Then she went to join them in the bright light of that unending Easter morning.

Editor's note: This reflection was originally published in the May 2009 issue of Celebration. Sign up to receive daily Easter reflections.