(Julie Lonneman)

Other homilies in this series have dealt, as this one does, with the Easter season and may be helpful in mystagogical preaching during the Easter season in 2006. The homily below is for the Ascension of the Lord, celebrated in most dioceses of the United States on the Seventh Sunday of Easter, May 28, 2006. Note that the text presumes the assembly has heard Ephesians 4, the reading for Year B, and not the second reading from Year A, which the Lectionary allows in any year of the cycle. The statistic on life sentences is from Human Rights Watch (NYC) and was given in the January 2006 issue of Harper's Magazine, Page 11.

Years ago, but not all that many, there were two church organists who loved the feast of the Ascension of the Lord, for it brought a twinkle to their eyes. One of them, playing during the collection, would subtly work in just a little bit of a then-popular song whose words included "Up, up and away, in my beautiful balloon." The other, more of a traditionalist perhaps, would play something meditative after Communion, but those who listened closely on Ascension Day would detect here and there the melody of the old song "Be it ever so humble, there's no place like home." One saw Jesus taking off from the earth. The other saw Jesus going home. Both made people smile, as did the homilist who would always bring to this day's sermon the wonderful quote from the escaped slave named Sojourner Truth. Once asked about death, she had answered: "Die? I ain't gonna die! I'm going home like a shooting star!"

"He ascended into heaven," or so we claim in our recitation of the creed. We generally don't let it bother us that the different accounts of Jesus' ascension in our Bible are not only quite different, but at odds with one another. Yet the story is the story and of course there will be different ways to tell it after so many years. And the geography? Sure, we modern people know that heaven isn't "up," and what's more, in a universe of suns and planets and galaxies and who knows what, even "up" isn't up and "down" isn't down. The Easter stories bring their reminders of how little all this has to do with physics: "Do not cling to me," Jesus tells Mary of Magdala. "Blessed are those who have not seen but have believed," he says to doubting Thomas. So while we may well begin the scripture reading today with the very first verses from the Book of Acts, even there the last words are a rebuke to the literal-minded disciples: "Why are you standing there looking at the sky?" The poor disciples still didn't understand. And neither do we most of the time.

All of Easter's days and Sundays with their scriptures and their songs, their sprinkling of blessed water and their honoring of the great candle lighted at the Vigil liturgy, all of this has brought us to these last days of Ascension and then Pentecost. Stories of Jesus talking with and eating with disciples after the crucifixion fill the early weeks of Easter season. We are every Easter striving to know: What does it mean that we have died and come to new life in the waters of baptism, this year or years ago the same? What does it mean that we have put on Christ? What does it mean that we have come through those waters and now on the Lord's Day we seek out that conversation with the Lord, that table companionship with the Lord? What does it mean that we do this not as individuals but only as the church, this very assembly?

As the Fifty Days of Easter continued, we moved from those stories of meals and conversations to some beloved texts like the Good Shepherd and to puzzling, hard texts — a little vague perhaps — about vines and branches, about the commandment to love one another as the sum and substance of it all. And in the first readings each Sunday we've been hearing snippets from how the church remembers its infancy and tells it in the book of Acts. We never hide the fact that even in the beginning it was a mess, as it still is today. We heard, for example, of Paul's early days as a Christian. Newly baptized in Damascus and now come to Jerusalem, both cities under the heel of the Romans, he gets introduced to Peter and others who wonder what this ball-of-fire and their former enemy is up to. And we heard another story about Peter and how his own views had to change when he saw that God's Holy Spirit wasn't bound by Peter's very convenient way of fencing in the church. It is an old story but we need to tell it again and again.

So we have come again into these final days of the Easter season. A late Easter this year has put us already at the end of May, Memorial Day weekend, when we finally tell of the Ascension. In the second reading, we heard a paragraph of Paul's letter to the church at Ephesus, a city in what is now the nation of Turkey. That reading, the one that had nothing to say about skies and clouds and angels, is today sandwiched between the stories of Jesus' ascension. The writer of the letter wasn't expecting Jesus to come back any time soon. The writer wanted the church to come to grips with what it might mean to live day by day and year by year, a whole lifetime, as a baptized person.

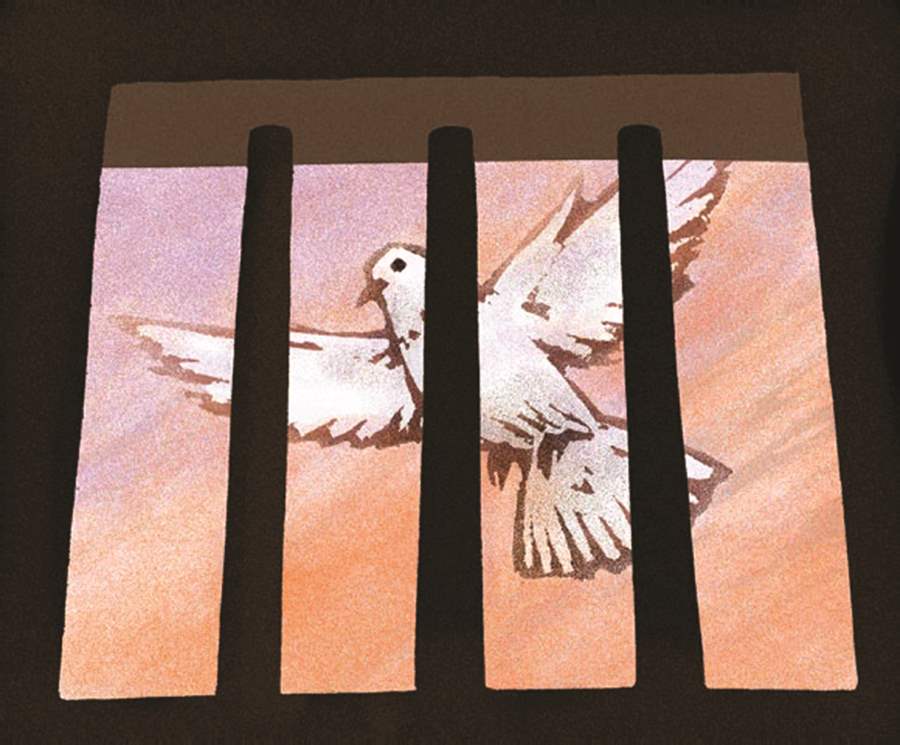

It isn't clear whether Paul himself wrote this letter or if it was some disciple of Paul's. Today we heard this opening line: "I, a prisoner for the Lord, urge you to live in a manner worthy of the call you have received." A prisoner for the Lord. Whether Paul wrote the letter or not, the writer almost casually indicates that being held in prison by the powers-that-be, as Paul was, is not unusual for a follower of Jesus, but also is not without importance. Reminding the readers of the letter that it comes from a prison cell should have told them as it does us: There should be nothing surprising to any of us about a follower of Christ being in jail. Nothing surprising, but still something to be pondered. Fifty years ago Christian preachers in America often went on and on about how Christians were being put in prison in communist nations. Then one day the leaders of America's Christian churches were forcefully addressed by a letter written to them by Martin Luther King Jr. not from a prison in Russia but from his jail cell in Birmingham, Alabama. Don't you see, he was saying, that doing what the Gospel tells us right here will likely get us locked up?

In the life's work of a Christian, one occupational hazard is being sent off to prison. In this very year, in this very nation, there are Christians who are prisoners for the Lord, locked up for months or years, like Paul and like Martin. Some of these prisoners for the Lord today are doing time for trespassing. They walked across some forbidden lines and denounced the deeds that are being done there. Some have trespassed where our government stores our weapons of mass destruction, nuclear or chemical. Some have trespassed where our government teaches effective ways of repression and even torture. These prisoners for the Lord challenge the rest of us as Paul challenged the early churches and Martin challenged the church in the 1950s and 1960s: What is your baptism about? What are your Sunday assemblies doing? Are we building up the body of Christ when we close our eyes and close our mouths and accept so quietly the way the world is being militarized and the very life of planet earth threatened so that a tiny minority — ourselves among them — can continue to live in the present manner?

There is such irony in Easter. Will we proclaim that Christ burst the bonds of death and trampled on the powers of evil? Will we then strive, as Paul writes today, to ourselves achieve together as church "the full stature of Christ"? What is that stature? What does that Christ look like? The bonds of death are still pretty strong around the world. The powers of evil try to work out of sight, but really it isn't so hard to see what's going on if we tear away the distractions they toss daily in our paths. What we renounced at baptism is not the stuff of fairy tales. We renounced, every one of us, the everyday ways that evil pokes through our lives, the everyday ways we so easily get used to taking care of our own agendas and comforts and barely notice what violence has to be done to keep the food on our shelves, the gas in our cars, the electricity in our appliances, the clothes on our backs.

Advertisement

When this church assembles on the Lord's Day, what is to become of us as we do our work here? What can hearing and pondering the scripture week-in and week-out make of us? What happens to a church that pours its whole energy into intercession? What becomes of a church — that is, ourselves — that gives loud and intense thanks to God whose love was found in the crucified Jesus, whose mercy is manifest in every new morning? What sort of people are we then when at last we eat and drink at this table one cup and one bread, this food and drink, this body broken for us and this blood poured out for us? Are we still standing here gazing up into the heavens, without a clue?

Let us bring ourselves down to earth and look at just one of so many needs that summon us to get about the tasks we accepted when we were baptized.

We heard today from Paul in his prison. Have we thought about, prayed for, written to, listened to those in prison now, not just those like Paul or Martin who went there for the Gospel, but those who went there because our society has made prison an industry, because we have decided to keep two million people there day after day and punish them? Do we accept responsibility for being the nation that keeps in prison a larger part of the population by far than any other nation in the world? Here is one of many numbers we could ponder: In the United States there are 2,225 persons serving sentences of life in prison for crimes committed while they were juveniles. Live all your life in prison and then die? In all the rest of the world, where 19 out of 20 people on earth live, there are a total of 12 persons serving sentences like this.

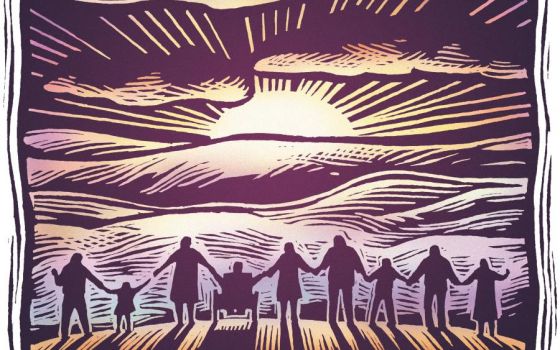

What is to become of us? We ask that as we try to see what it would mean to live in the Easter mercy of God. What is to become of us? We ask that as we open our eyes to see for ourselves what deeds are being done around us and even in our name. If this ascension story has one simple meaning it must be that Christ leaves us here to do the Gospel work. No wonder that the church constantly cries out: "Come, Holy Spirit."

Editor's note: This reflection was originally published in the May 2006 issue of Celebration. Sign up to receive daily Easter reflections.