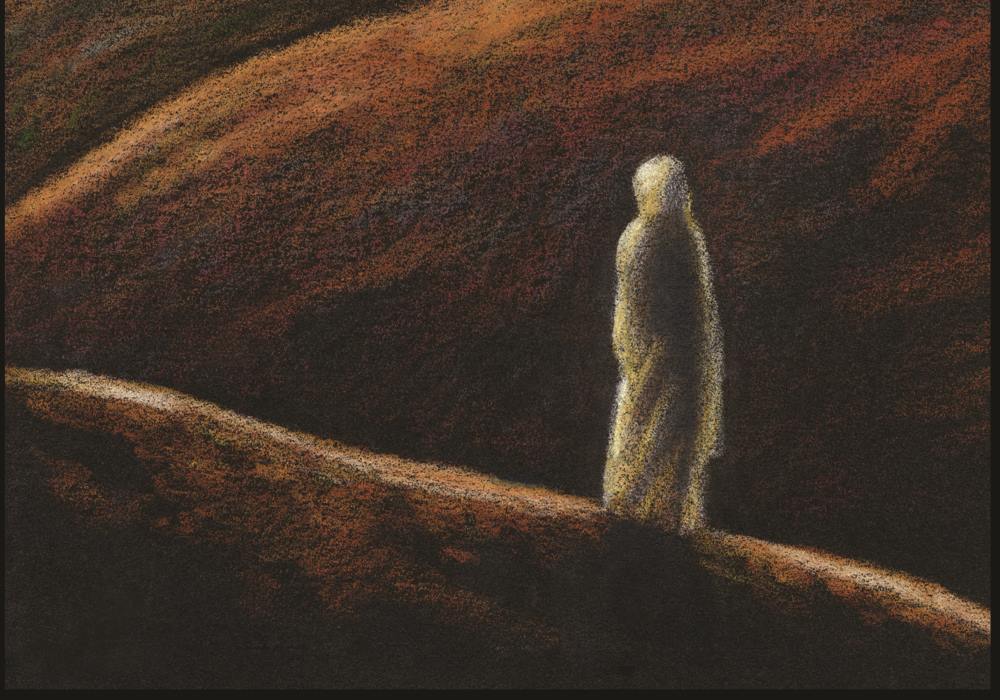

(Julie Lonneman)

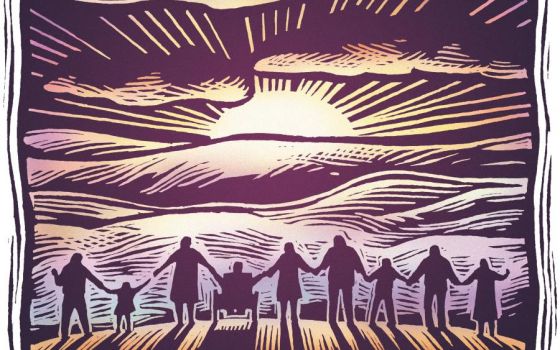

We had sailed at dusk on Florida's Biscayne Bay. We were out for about four hours when our captain turned toward home. Usually, in other sails, she had turned on the engine as we approached the dock. Her boat, a sailing instructor's boat, is docked at the far end of the marina in a corner, a bit of a tight squeeze but not impossible, with the engine going. This night she got a twinkle in her eye as we turned toward home. "Let's try it without the engine. I think the conditions are right." Minutes later, she added, "We may have to turn the engine on at the last minute so be ready … we won't know till we get close." Moments later we glided, soundlessly and effortlessly and enginelessly, into the berth.

There was a calm in that moment that deserves respect and attention. It was more quiet than I have ever heard. I used to think you couldn't hear quiet. Now I know you can. It was less effort than I have experienced in a long time. Effort is a persistent intruder in my life: even getting to this sail had required it. I didn't know if I had time, didn't know if it would be enough fun to warrant the time off and away, wondered if I had brought the right dish for my part of the potluck, blah blah blah. Enginelessness, however, was an utterly new experience.

Enginelessness is on the other side of effortlessness: It is not the absence of struggle so much as the presence of peace. I want more life with the engine off. I want its quiet most of all.

This little experience caused me to become quite interested in Jesus' words on abundance. I have always been mean toward them. "I have come that you might have life and have it abundantly," he says. What's wrong, I have always quipped, with just life? Isn't life good enough? Why the push for more and more? What's wrong with is and is? Alive and alive? Isn't the engine required for abundance damaging to nature? We are after all, part of nature, and if nature gets ill, so do we. Is there a kind of powerful engine or an abundance that protects nature from us?

Is the John text no longer useful in the world of clutter, where some human beings have actually decided nature is for us and not we for nature?

In "Small Silences: Listening for the Lessons of Nature," an essay in the July 2004 Harper's, Edward Hoagland (a nature writer and lion tamer) says, "It is hard to even find a sight line without buildings, pavement, people….. and we're not even awed by each other any more. Even people are too much of a good thing" (52).

Before I point the sail back in the direction of John's report of Jesus' words, let me give Hoagland one more say. Verbal clutter can be as difficult as material clutter, so I want to be careful. But I also want to dialogue with this naturalist about Jesus' abundance.

Froth

As a biologist, Hoagland thinks that God created the world for the bubbles. For the froth. In other words, God wasn't using engines functionally, to get from one place to the other. God was developing engines for their fun and froth, their evidence of the magnificence of creation. Perhaps abundance is frothy instead of functional. One sail like this particular night's sail is plenty. Having to work harder to get a bigger and better boat is too much. There is a difference between abundance and too much, and way too many of us know it.

We know the difference between abundance and saturation. Hoagland says, "Glee is like the froth on a beer or on cocoa. Not essential. Glee is effervescence. It is bubbles in the water, beyond efficiency, which your thirst doesn't actually need." Hoagland doesn't have much to say about God, only this: " … the thread in God's creation is … ebullience … The choosiest females choose not just for strength or money. but also for the superfluous energy that humor and panache imply." Hoagland reveres evolution more than most people revere God.

The peace of enginelessness is also frothy. It moves beyond the world of evolution and utility and gotta gotta gotta. Enginelessness is not useful at all. But without its peace, life is just bread, just "gotta eat," just biological, just repetitive effort on behalf of the species active in us and after us.

Some people have figured out the way to engineless abundance. I think of the Italians who speak of the "sistemati" or settled way of the evening stroll, the passeggiatta or the bella figura. They swear that change only comes so that things may stay the same. They find purpose for life in the pursuit of beauty. Beauty is the saving grace of evolution. Beauty saves the grace in evolution. Another key to enginelessness is to find peace in beauty. We know that Bach's concerti were beautiful because of what he left out as well as what he put in. Even hot chocolate can have too much froth – and spill and stain and make a mess of what otherwise might have been sheerly and purely delicious.

Turning off the engine is a good idea if we want peace or beauty or quiet in our life. You don't have to be a poet to understand this meaning. You don't have to out-Bach Bach. You can be an ordinary person living an ordinary life. I went to the store to buy a new pair of blue jeans. The clerk asked if I wanted slim fit, easy fit or relaxed fit, regular or faded, stonewashed or acid washed, button fly or regular fly … and that's when I started to sputter. Can't I just have a pair of blue jeans, size 14?

Advertisement

Satisficers vs. Maximizers

Sociologists join ordinary people and poets in understanding how more is often less. There are two kinds of people, according to Barry Schwartz in The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less. Satisficers are the ones willing to live with the good enough rather than insisting on the best. Nobel Laureate Herbert Simon developed "satisficers" as a realistic alternative to always maximizing all utility all the time. The "all utility all the time" people are multitasking the world to its and their grave; Schwartz calls them maximizers. He argues strongly for the satisficers being the ones who have the best lives.

He uses the example of a supermarket chain attempting to calculate the very best alternative before deciding where to place a new store. If they go too far, the research costs will bankrupt them while quicker competitors move in. Satisficers know when to turn off the engine. Maximizers are the half-empty-cup people. They feel worse about loss than gain, even if both matters are equal. They resemble the pastor who gets nine compliments at the end of church on the sermon but can't forget the one complaint that was also uttered. Some people just program themselves always to be brutally aware of what they are not getting. They have lost the ability to turn off the engine.

A minister giving a sermon at a wedding shocked the congregation by saying that the grass is always greener on the other side. There will always be someone prettier, funnier and smarter … but marriage is not a matter of comparison-shopping. "Considering your decision irrevocable allows you to pour your energy into making things better." Turning off the search engine for a better mate creates satisfaction — not maximum satisfaction, but satisfaction nonetheless. This satisfaction is not self-destructive. It does not hurt itself in the name of something better.

Interior decorators join the accumulated wisdom about the engine. "Fewer finer" is what every decorator will tell you. Gardeners too. Pruning a bush makes it grow beautifully. Letting it overtake your yard has nothing to do with beauty.

That's why my favorite phrase is TMI, or "Too Much Information." Enough already is my response to most matters.

Turning off our engines gives us a capacity for quiet. It builds a confidence in solitude. It is a good way to live: Engines are important some of the time but not all of the time. Jesus did come so that we might have life and have it more abundantly.

Turning off our engines and sailing quietly all the way home is also good practice for dying. We glide into our next birth, ready, grateful and without a lot of noise in the background.

Editor's note: This reflection was originally published in the May 2005 issue of Celebration. Sign up to receive daily Easter reflections.