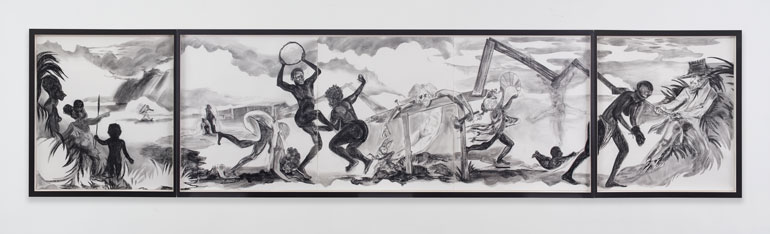

"Easter Parade in the Old Country" (2016) by Kara Walker (Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York)

A Cleveland Museum of Art exhibit of 31 drawings, ranging in size from roughly a sheet of computer paper to pages that cover walls, draws upon renowned artist Kara Walker's residency at Rome's American Academy of Arts earlier this year. In much of the artist's work, what can look alluring and beautiful from across the room reveals, upon close inspection, troubling inhumanity and cruelty embedded within the picturesque. A landscape in a Walker exhibit is no postcard view; it's likely to include shockingly graphic abuse, and worse, occurring in plain sight. The show in Cleveland, "The Ecstasy of St. Kara" (through Dec. 31), features that same dichotomy.

From a distance, "Easter Parade in the Old Country" (2016), contains figures that could be frolicking, but from a closer vantage point, there's a great deal of pain. A crucified individual, attended to by a Br'er Rabbit character, is nailed to a wooden contraption that's not exactly a cross. In his left hand, he holds a hammer that may suggest he's inflicted some of the damage himself.

Another figure who looks suspiciously like the crucified one pulls a black woman along using a noose tied around her neck; a black child clings to her scant garment and gets dragged along the ground.

One of very few wall labels in the exhibit explains that the "simultaneously unresolved" elements of the drawing display "various histories anachronistically at play," in which "paradoxical imagery from Christianity and African American folklore references the transatlantic slave trade and its reappropriation of biblical themes for the purposes of racial subjugation." Alluding to the symbolism of the crucifixion and the Man of Sorrows is also part of the piece, the label states.

The work, however, raises many more questions than it answers. What precisely are the contours of this use of biblical themes for racial injustice, and is the claim being made that this is endemic to the Christian Bible?

In fact, it's difficult to find any faith tradition in which some -- if not many -- haven't cited chapter and verse to justify hosts of evil plots and programs. Antonio reminds us in "The Merchant of Venice" that the devil is able to cite Scripture for his own purposes. Is the claim being made here that Scripture itself is the culprit? Or that it should be handled with care?

And the anachronisms, although diverting, don't necessarily shed light on broader truths or observations. The show is packed with references to slavery in the United States and to Black Lives Matter, which are juxtaposed with the history, art and architecture of Rome, including its religious history. But aside from a somewhat opaque essay in the catalog by the artist, little context is offered.