(Julie Lonneman)

I attended a high school youth ministry retreat many decades ago. There were several dozen of us gathered at a Benedictine monastery in the mountains, and I remember we had a conversation about the Holy Spirit. I do not remember the details, but I do remember that a parent volunteer finished up our conversation with the story of a larger outdoor arena mass. At a key moment in the Mass, a dove flew overhead, and everyone grew quiet. It was a dramatic story, but I remember even at that young age feeling as if somehow this was missing the point. Was this really how God operated, soaring over stadiums as a bird to amaze the flock? Since I had never seen a dove before, I wondered if it bore some resemblance to another white bird I was very familiar with — the scavenger seagulls that populated our parish blacktop in search of discarded food.

Imagining God in any form remains a tricky business. The cartoonist, blogger and former Pentecostal pastor David Hayward — who goes by the amusing moniker of "naked pastor" — developed a cartoon I often use teaching university theology classes. His cartoons are very simple; this one portrays a box labelled "theology," and a little man is trying to jam the oversized figure of God into the small box. Theology, I remind my students, does not only consist in academic chatter about sacred things or professional preaching on Sunday. It is all human talk (logos) about God (theos), and about human life in the light of God. Unfortunately, too much of what human beings have to say about God falls right into the pattern lampooned in the cartoon. We cram God into a box far too small to encompass Divine Mystery. In effect, we domesticate God for our purposes, make God over in our own image instead of somehow acknowledging ourselves as made in God's image.

Most of us remain at least a little aware of the dangers of remaking God in our image when it comes to the first two persons of the Holy Trinity. Parents recognize that the fatherly God whose divine reproach they dangle in front of their children seems suspiciously aligned with their own disciplinary intents. Many people note the weird spectacle of affluent prosperity preachers on television speaking of wealth as a blessing from Jesus, the same Jesus who in Luke's Gospel says: "Woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation" (Luke 6:24). But what about the third person of the Holy Trinity? Are we aware of the dangers of domesticating the Holy Spirit? Perhaps there should be a cartoon with a person shoving an oversized white dove — the usual icon of the Holy Spirit — into a tiny box.

A certain prelate, who shall remain nameless, remains an obstinate opponent of any innovation whatsoever, ecclesial, ethical, liturgical or otherwise. The secular world threatens to crush the church around every corner, and, according to him, the only defense is precise attention to the rubrics of the liturgy (better yet, observe it in Tridentine Latin) and a doctrinal purity that looks suspiciously like 19th century Catholic authoritarianism. Exasperated by his periodic statements, I once turned to a wise priest I know for explanation. He simply said, "He has no pneumatology." Pneuma is the Christian Scriptures' word for the Holy Spirit — it means wind and breath. My priest-friend meant to say that the bishop in question had precious little provision in his way of thinking for the spontaneous work of the Holy Spirit in the church. It would be fairer to accuse him of having a truncated, trickle-down pneumatology. The Holy Spirit works in the church, but only along prescribed liturgical and doctrinal pathways easily recognizable to him and like-minded colleagues. For him, the Spirit does not, as John's Gospel puts it, blow where it wills (John 3:8).

Across most of Christian tradition, however, the Spirit does blow where it wills. In the Bible, the Spirit's work has a wild, unrelenting and unpredictable character to it. True, God's spirit blows over the chaos of the waters establishing order in the first creation story (Genesis 1:2), but God also breathes life into unruly humanity (Genesis 2:7). More to the point, the Spirit speaks through the prophets. They go only where the Spirit sends them, and do only what God asks, no matter how dangerous or odd. Ezekiel eats a scroll; Isaiah preaches naked; Jeremiah hides his underwear in a rock until it rots; Hosea marries a prostitute. These prophets admonish kings, heal enemy generals, defy religious authorities, attack the wealthy, and criticize the people in general for their neglect of justice, their infidelity to God, and their mistreatment of the poor and the stranger. They point to upheaval and even destruction.

Some would then argue, "Yes, but that was the Old Testament. What about the New Testament?" Yet the Spirit proves just as unpredictable there. When we think of the Spirit in Christian Scripture, the first story we recall is the Pentecost (Acts 1), when the Spirit comes over the apostles and gives them power to have their message about Jesus heard by people of all different languages. The resulting commotion leads many of those present to assume that the apostles are drunk at nine o'clock in the morning. In the Johannine and Pauline traditions in Christian Scripture, the Spirit transforms each believer as God wishes (not as that particular believer would have it — just ask Saul of Tarsus). In Luke and Acts, the Spirit's words erupt unexpectedly in the mouths of Elizabeth the elderly and childless cousin of Mary (Luke 1:41), in Peter the feckless denier, and in Paul the persecutor. The Spirit compels Peter to baptize a group of Gentiles (Acts 10:44-48). In Paul's own letters, the Spirit speaks through prophetic gifts given by God's judgment to specific believers (1 Corinthians 12), and mysteriously on behalf of all believers when we stumble in our prayer (Romans 8:26).

No wonder the chaos of wind is a far more consistent image of the Spirit in the biblical witness than the tidy image of the dove that usually comes to mind. The latter image comes from the scenes of Jesus' baptism in each of the four Gospels. Yet, even that biblical image of the dove has an unpredictable quality to it. The dove emerges as much from nowhere as the wind that carries it or the divine voice that accompanies it: "You are my beloved Son; with you I am well pleased" (Luke 3:22). In Mark, the Spirit identified with this dove immediately drives Jesus into the wilderness to face wild beasts and temptation by the devil. Amusingly, the biblical Greek word for dove also means pigeon; they are from the same ornithological family, and the birds the two words describe overlap. Perhaps it is not unfair to think of the divine barging into the world like a pigeon, that ubiquitous, speckled, obnoxiously cooing purveyor of urban trash. Instead, contemporary iconography of the Holy Spirit has tended toward a clean and pure white dove, the kind released at weddings and other public events. This Holy Spirit seems excessively tidy, highly orchestrated, a Spirit we can control and contain. This Spirit feels like a safe option for confirmation pins and church bulletins.

In fact, for some theologians the dove has become such a symbol of the domestication of divine imagery that they have warned us to remember that the Holy Trinity is not literally "two men and a bird." Truthfully, much of church history might be thought of as a kind of pneumatological cold war between the unruly wind and the sedate dove. St. Paul celebrated the gifts of the Holy Spirit scattered upon the faithful, but he also warned Christians in Corinth not to take themselves too seriously as recipients of such gifts.

Advertisement

The first century Didache offers criteria for sorting out the true Spirit-inspired prophets from pretenders; true prophets practiced what they preached, did not ask for money, and did not overstay their welcome. Throughout Christian history, new Christian movements emerged when committed individuals looked for a mystical light coming from the Holy Spirit or discerned in themselves special charisms from the Spirit for voluntary poverty, the mystical life, preaching or leadership. Not a few came from classes or groups ordinarily excluded from such activity or pushed to the sidelines — women, the poor, marginalized members of religious orders. Especially when the social order, orthodox teaching, or their own authority seemed at stake, church officials responded uneasily. Some of these Spirit-haunted groups turned into respected religious orders such as the Franciscans, others into barely tolerated movements like the beguines. Others ended up burned at the stake for heresy.

On the one hand, those of us involved in ministry can appreciate some of the church officials' concerns. The Spirit blowing where she wills presents a dangerous kind of divine working. Anyone can come along saying the Spirit blew them in to take charge. If we, like the early church, really believe in the Spirit at work among us, then we also have to have ways to "test everything" (1 Thessalonians 5:21) to see that it really comes from the Spirit.

Most human beings impress easily. Tickle our emotions, stoke our fears, ply us with seemingly ironclad rational arguments, and we let our guard down. Present us with a leader with good looks, charisma, or towering strength, and we forget to ask whether or not their actions seem to lead to good things for all. St. Teresa of Avila noted that she would prefer a sister who swept the floor with love than one capable of levitation and all sorts of extraordinary feats. In all of Christian tradition, the primary test remains that of love without limit or distinction; the Spirit only leads to people doing good for others, especially for the poor, the marginalized and the stranger. After all, as Jesus noted, they cannot do you much service in return (Luke 14:14).

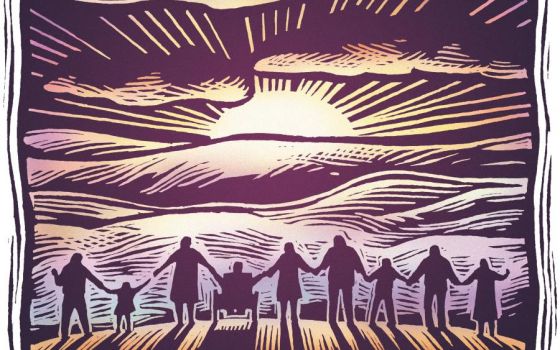

On the other hand, and perhaps more fundamentally, we all fear how a mighty, holy wind can get out of hand. As with the aforementioned bishop, a part of me is addicted to control and order (not to mention comfort). He and I both worry that the wind may come and blow everything irrevocably off course. We may not like or understand what develops as a result (better the devil you know). Indeed, most of us experience dramatic changes in our spiritual landscape as painful, but they often serve as instruments of metanoia, a holy change of mind and heart. Some years ago, a beloved mentor who had always seemed like a tower of strength suddenly had a devastating heart attack. In the months that followed, I found myself accompanying him at the edge of death, and then in a long, bewildering recovery process. We both began to understand that the extremes of human vulnerability do not overtake us on schedule or at a moment of our choosing. If they did, we would continue to depend on ourselves instead of on God. True, the Spirit does not always make such demands on us. Especially when we remain powerless, the wind comes and soothes us or makes us feel alive again. But as soon as we grow grandiose and unresponsive to one another, it whacks us over the head with a two-by-four.

The Spirit as holy wind comes from nowhere to animate not only us personally but the whole church, according to God's plans, not our plans. In the context of ministry, this means that the broken human beings whom we encounter every day are not interruptions or irritations. They are not our clients or ignorant Catholics who should know the liturgy or church teaching better. They are not burdens to us but the body of Christ, and the Spirit has blown them our way so that we might encounter Christ in them. This includes, for example, insecure and quarrelsome committee members, narcissistic leaders of ministries or apostolic movements, couples who come for marriage preparation only out of parental pressure, immigrants who come with Catholic customs strange to us, and international priests whose accents in English we have trouble deciphering. While we might think we are there to help them, they have come to teach us and them together something about God's love we could not understand except in this particular encounter. Communities that know this have created what Pope Francis calls "a culture of encounter." They make space for the anawim and the sinners and recognize the brokenness and weakness even in the strongest or most accomplished people. They are the "field hospitals" of which the pope speaks.

Yet the temptation persists to forget all this and wall ourselves off from the unpredictable needs and mixed motives of the unruly people of God. A friend reports that, on Christmas Day, at the hour at which an overflow mass was scheduled to begin in the parish hall, the pastor came and locked the doors to teach the latecomers a lesson. This seemed to me as good a sign as any that we badly need a good pneumatology of the wind. Part of the reason the holy writers chose the wind as an image of God was to remind us that God does not work by our rules. The Spirit blows where it wills, not where we would like.

The traditional Roman Catholic prayer to the Holy Spirit begins, "Come, Holy Spirit, fill the hearts of your faithful and enkindle in them the fire of your love." But the second line, borrowed from Psalm 104, verse 30, tells us that the Spirit comes to renew the face of the earth. How can the Spirit renew the whole earth without stirring things up a bit, without pushing us all beyond their comfortable expectations? Renewal presumes change, conversion. We will all have to learn to see things differently, to learn to "clothe yourselves with the new self" (Ephesians 4:24, NRSV) as the Spirit directed the Ephesians. But human beings, myself included, remain stubborn. Most of us would probably prefer to fight the wind. But the Spirit will renew the earth (and the church) with or without us. It is only a question of whether we would prefer to hunker down and be buried in the chaos of what the wind stirs up, or to allow ourselves to be carried aloft by the irrepressible wind of God.

Editor's note: This reflection was originally published in the May 2017 issue of Celebration. Sign up to receive daily Easter reflections.