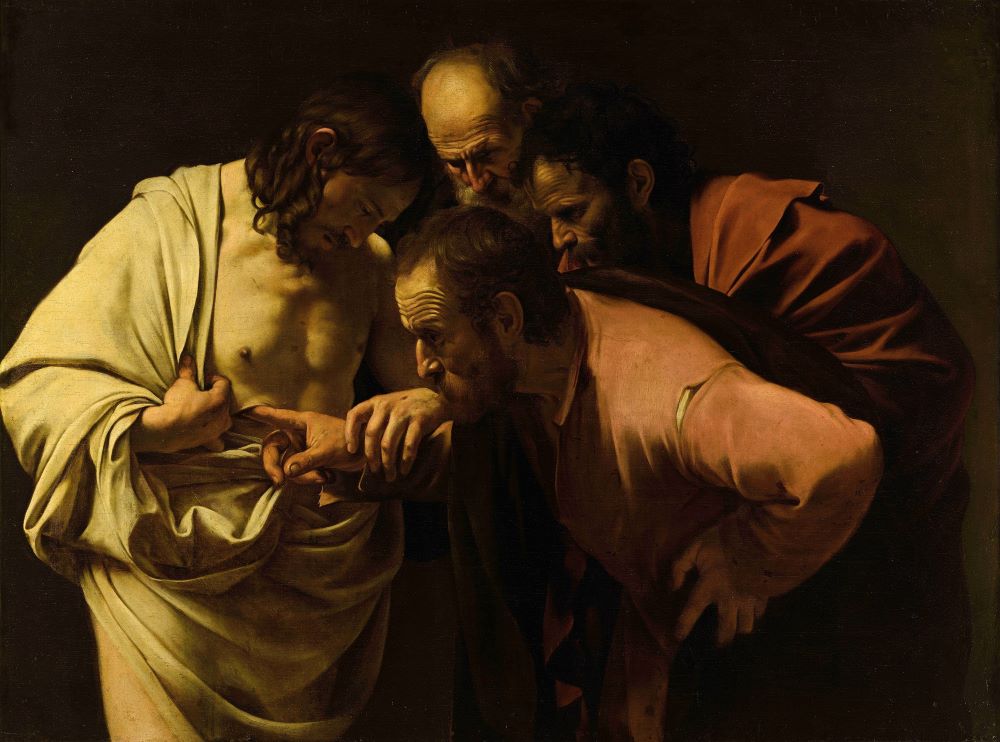

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio's "The Incredulity of Saint Thomas" (circa 1604) shows the moment the apostle Thomas came to believe in the resurrection of Jesus Christ. (OSV News/Public domain, Wikimedia Commons)

"Empty" can mean scarcity, lack. But it can also mean quiet, solitude, rest. Imagine an empty beach. An empty inbox.

Doubt is a kind of empty. But religious doubt is often portrayed as a negative, like spoiled meat in a spiritual pie. Doubting Thomas has gotten such a bad reputation over the years that he's known culturally just for his doubt, not as a twin, or even really as a disciple. But what else can Thomas teach us?

When I studied theology, I learned that there were two ways to approach the Divine. One was through knowing and one was through doubt. Technically they are called the kataphatic way and the apophatic way. The kataphatic way is the one we're most familiar with — we know God through what we believe. We have ideas about God from the Gospels, worship, song, theology, culture. Think of the kataphatic way as a spiritual fruitcake, studded with story and image, hefty with meaning.

The apophatic way is the negative way. We strive to understand the Divine through what God is not. The root of the word "apophatic" is the Greek word "to deny." When people describe an apophatic understanding of God, words may not come as easily. They aren't sure of what God is, but they have an idea of what God is not — God isn't about wealth or power or domination. God isn't male or female.

The apophatic way is an empty cup. People with this perspective may feel pressure to be more positive. Religious parents of young people with this approach may fret over their child's lack of faith or belief. They might miss the spiritual maturity and striving for God that their children are demonstrating, because they have been taught to value belief over doubt.

In many religious traditions, doubt is scorned or derided. From this perspective you could read the Gospel story of Thomas as negative. Jesus showed up, Thomas missed the visit, and he didn't believe his friends until Jesus came back and offered his wounds to Thomas. When reading the passage where Jesus says, "Blessed are those who have not seen but have come to believe," I used to get a little glow of pride that I haven't seen but I believe — look at me, better than Thomas.

Advertisement

Thomas doubts. When Thomas returns to his friends and hears the unlikely tale of their dead teacher showing up in their locked room, he doesn't believe it. What does he say he needs? He needs a physical, actual experience to believe. He doesn't want a story, an idea, an image, theology. He needs to touch Jesus' wounds.

He proclaims his doubt, asks for what he needs, speaks up loudly in his community. And what happens? Jesus shows up and gives Thomas what he asks for. Thomas' doubt builds a bridge to a connection with the risen Jesus. His doubt is rewarded with generosity.

Central to this story are the actual wounds on Jesus' body. I don’t know about you, but I always had this idea that after the Resurrection Jesus' body would be healed, with maybe just a faint shiny scar to remind us. But the wounds are still there. They aren't closed and healed, they aren't covered, they are gaping enough that Thomas could put his hand inside them, as Jesus invites him to do. The wounds are the proof. They recognize Jesus through his wounds. The crucifixion left a mark, scars that are perhaps transfigured, but not erased.

Sometimes I wish for a more obvious God, who keeps me in consolation and connection, who protects me and the people I love, brings only good things into my life and saves me from pain and trial and erases my wounds. I know it is more complex than that. The story that ends in the Resurrection starts with a yes. Mary says yes, I'll carry this child. Then Joseph says yes, I will marry this woman who carries a child that isn't mine, yes, I will raise this boy. Jesus says yes. We are all invited to say yes to the Divine in various ways throughout our lives. And sometimes that yes, even the yes to life itself, brings pain, loss, wounds, even destruction — of our ego, ideas, dreams or hopes. Sometimes our spiritual curriculum is to live in the doubt, be curious, ask for what we need and see what kind of bridge doubt may bring to a new intimacy with the Divine.