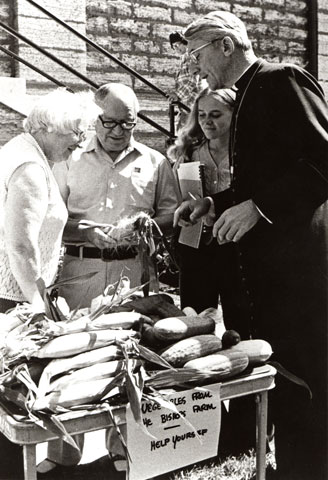

In 1975, Bishop Raymond Lucker, then auxiliary of St. Paul-Minneapolis, encourages passersby to help themselves to corn, cucumbers and beans from his farm. (CNS/Kati Ritchie)

"The other bishops said it was easy for Ray to speak out. He wasn't going anywhere," Morrie said, one finger on the steering wheel of his Prius as we cruised down Route 15. "The only ladder Ray ever climbed was the one he used to fix his roof."

Bishop Morrie and I were driving back down from Minneapolis to his diocese of Paris, Kan., passing through our old friend Bishop Ray Lucker's diocese of New Ulm, Minn. Ray had passed away almost 12 years to the day, Sept. 19, 2001. We were coming down from a meeting with his publisher outside Minneapolis where Morrie had discussed his new book on the rise and fall of the episcopacy in the United States. I was there for support and we just had to pilgrimage through the sacred ground Ray Lucker had trod for a lifetime.

"Just imagine," Morrie said, "a diocese of 10,000 square miles, farms and lakes and small towns. Larger than New Jersey. Ray used to drive his little Chevy to all 80 parishes. If there was a confirmation, he'd stay the weekend. Who does that?"

"You?"

Morrie harrumphed. "Paris, Kan., is Hoboken with corn stalks. Jersey has six dioceses and 12 bishops. New Ulm had only Ray."

"He must have known it like the back of his hand."

"He was born here. He studied in Rome during the council, ran the Christian formation department in D.C., but the only place he ever wanted to be was Minnesota."

"Like Ray Kinsella in 'Field of Dreams.' Someone asked him, 'Is this heaven?' and he said, "No, it's Iowa.' "

"Look ahead of you," Morrie said. "Behold the Midwest!" The white-ribboned road narrowed into a blue horizon as far as the eye could see. To the left and right were endless fields sprouting life in green and brown and yellow. Growing up here had to mean that anything was possible and that you could do anything.

"Look, up there!" Morrie said. A piece of wood that looked torn from a barn bore white letters that said, "Fresh Fruit and Veggies." Morrie braked three times and pulled to the side in front of a table with tomatoes and berries and corn. "Ray used to stop at these stands on his way home and buy food for the community. He didn't live in manse, you know. He lived in a prayer community with a few other priests and nuns, and he loved to cook. C'mon."

A Hispanic man wearing a straw hat got up from a lawn chair. Morrie smiled and said, "Buenos días, qué pasa?"

"It's all good. Please help yourself."

Morrie took a lot of everything, and paid in full. We put five bags in the back seat. You could smell the fresh berries as we continued our journey. "You know," he said, "Ray used to make his own jelly. 'Lucker's is better than Smucker's,' people said. He used to stop along these roads and pick wild mushrooms, too. Made his own soup, he did. Better than Paul Newman's. I testify."

"Was he your best friend among the bishops?" I asked.

"Yeah, him and John O'Connor, both of them real people. If Johnny had been alive when 9/11 happened, he'd have been the first one there, lifting up rocks and searching for bodies. Ray would have been there, too, if he wasn't dying."

"I called him at the hospice the week before he died," I said. "I asked him how he was doing. He said, 'I'm just sitting here and letting Jesus love me. Who says that?' "

"I remember at his funeral a woman from the Dakota tribe placed a beaded medallion on his coffin. I asked her what it meant. She said it symbolized his friendship with Native Americans. 'Before the good bishop,' she said, 'the church didn't really accept us here. He made us comfortable.' "

"He had a special bond with migrant workers, too."

"Oh, yeah," Morrie said. "When Ray learned that Catholics were shouting filth and obscenities at Mexican workers who had no choice but to live in subhuman conditions, he made it loud and clear how much it pained him and wounded everyone when such beautiful, gentle people were treated so badly. He urged parishes to reach out to migrants and he started new diocesan programs to improve their quality of life."

"Wasn't Ray the first bishop to advocate women's rights in the church?"

"From day one. Ray hosted open dialogues with women from every parish on the role of women in the church. He pushed the ordination of women at the annual bishops' conference year after year after year."

"What did the other bishops say?"

"They said, 'Thank you. Shut up. Sit down.' That didn't deter him. He wasn't going anywhere."

"Didn't anyone back him up?"

"Not really."

"Afraid of Rome?"

"Afraid of losing their status in the club."

"You, too?"

"You know me. I can't stand conflict. I fibrillate."

We drove in silence.

Morrie looked at me. "You know," he said, "Pope Francis held a dinner under the stars in the Vatican gardens for a hundred nuncios from all over the world this summer. He told them to beware of anyone who wants to be a bishop, that a bishop must never be ambitious or have the mindset of a prince. The true bishop is a good shepherd who lives a simple lifestyle and is close to his people and looks after them."

"I remember," I said. "He could have been talking about Ray."

We slowed to 25 miles an hour as we passed through a small town. At the opposite side of a traffic circle was a small wooden church with chipping white paint. A sign in front with little movie-marquee letters said, "Our Sundays are better than Dairy Queen." Morrie pulled into the driveway, in front of the side door. "Get the groceries," he said.

We put the bags on the three steps leading up to the door. Morrie pulled a little notepad out of his pocket, tore out a piece of paper, and wrote something on it. He placed the note in the top paper bag.

We got back in the car and drove to Kansas, nibbling on berries. They were good.

[Michael Leach is the publisher of The People's Catechism: Catholic Faith for Adults, edited by himself, Raymond Lucker and Patrick Brennan, and Revelation and the Church: Vatican II in the Twenty-first Century by Raymond Lucker and William McDonough.]