Presidential candidate Joe Biden takes selfies with Loras College students at a campus event Oct. 30, 2019. Catholic university students in Iowa could be part of a seismic shift of young voters in the caucus and eventually the general election. (Trent Hanselmann/Loras College Marketing)

In 2016, Brock Timmons was a high school senior in Davenport, Iowa, where he "grew up Republican" — as he describes being raised by politically conservative and Catholic parents. Timmons wasn't that interested in politics, but he cast his first vote in a presidential election for Donald Trump, because that's what Republicans did.

"I fell for the ploy that he's for the working class, that he's for the Christians," said Timmons.

But that all changed when he started taking social work courses at Loras College in Dubuque and began seeing what he describes as an "inconsistency between the conservative view and the Catholic view."

"Every day social workers help people get on their feet, but it's like putting a bandage on a gushing wound," Timmons told NCR. "We're not doing anything to fix the system that's causing all these problems."

Those insights led Timmons, now a college junior, not only to change his political affiliation but to volunteer for the campaign of the presidential candidate he believes talks most about systemic change: Bernie Sanders.

Young voters like Timmons are often dismissed because, as a group, they are less likely to turn out to vote. But voters under 30 — including Catholic ones — have the potential to have an enormous influence on the 2020 presidential election: "a progressive youthquake," as author Charlotte Alter put it in a recent Time cover story about how Millennials are changing American politics.

In Iowa — especially in the Catholic enclave of Dubuque — young college students at a Catholic school like Loras could be part of that seismic shift. Dubuque college students told NCR that their political involvement, activism and priorities have been informed by their Catholic faith — whether they are active churchgoers or not.

Millennials (those born roughly in the 1980s and '90s) already are the largest living generation, and they outnumber Gen X (born 1965–1980) and will soon outnumber baby boomers (born 1946–1964) among American voters, according to Alter.

Although life circumstances — not to mention gerrymandering and other voter suppression efforts—contribute to low turnout among younger voters, millennials doubled their turnout in the 2018 midterms, Alter said. If the 60 percent of millennials who say they plan to "definitely" vote in 2020 show up, their turnout would approach senior citizen turnout, she said.

And younger voters — like Timmons — tend to be more progressive than their parents and grandparents, according to a study by the Pew Research Center.

"My views really stem from Jesus' message — 100 percent," said Timmons. "I've definitely gone on and off with my faith, but one thing that's stayed consistent is Jesus' message of loving your neighbor and of seeing him in everyone."

Morgan Muenster, president of Loras College Democrats, welcomes Joe Biden to an event on campus at the Catholic college in Dubuque on Oct. 30, 2019. Muenster said she plans to caucus for Elizabeth Warren. (Trent Hanselmann/Loras College Marketing)

A lifetime of Catholic schooling is where politics and history major Morgan Muenster learned about compassion and human rights — ironically the very values that she eventually saw lacking in the church, prompting her to leave.

But those values show up in her progressive political beliefs, which focus on issues such as care for the environment, racial justice and women's rights. She sees the need for structural change and describes herself as a democratic socialist because "it all comes down to that we need to control capitalism."

In the Democratic primary, Muenster liked Julian Castro and Cory Booker but plans to caucus for Elizabeth Warren, whom she believes has a "better plan" than the others. That Warren is a woman is "an added bonus."

A Catholic county

Located in the northeastern edge of Iowa, Dubuque is divided from Illinois and Wisconsin by the Mississippi River, a geography that contributed to its evolution as a manufacturing center.

It is heavily Catholic, with as many as 78% of those who claim a religious affiliation identifying as Catholic, although the region is older and whiter than the broader U.S. church.

Dubuque also is the home of no fewer than five institutions of higher education, including two Catholic colleges: Clarke University, founded by the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and Loras, a diocesan school.

Dubuque historically has given Democrats "healthy victory margins," according to Iowa Starting Line; but not in 2016, when for the first time since 1956, a Republican presidential candidate won the county. Trump's win in Dubuque with 47.2% of the vote to Clinton's 46% (only 610 votes) is compounded when compared to the previous presidential election. Not only did Trump get 2,180 more votes than Romney had in 2012, but Clinton received 5,918 fewer than Obama had.

Iowa Starting Line attributes the flip to high turnout among rural Republicans, some blue-collar Democrats switching to Trump and low turnout among reliable Democrats. But there is also a generational component: While "older Democrats flipped to Trump," younger ones either moved to third-party candidates or stayed home. According to Iowa Starting Line's precinct-by-precinct analysis, "Especially around Loras College, voters simply didn't turn out."

"People are tired of establishment politics, whether liberal or conservative. They want something new."

—Carlos Garrido, senior at Loras College

While canvassing on the town's three college campuses as part of his internship with the Sanders campaign, Timmons says he sees a lot of disillusionment that has led to political apathy among his peers. "Everybody sees a bunch of people yelling about stuff that doesn't matter to them," he said.

But their ears perk up when Timmons talks about student debt, health care or what he sees as the most urgent issue, the "prison industrial complex."

For Ragan Carey, a sophomore elementary education major at Clarke University, education, families separated at the border and "the common good" are issues that matter to her, but she admits the issue of abortion makes choosing a candidate — or even a political party — "messy."

She leans Democratic, but said that "as a Catholic, it's hard to choose a side" because neither party fits perfectly with her Catholic values, which include a respect for life. She only recently was convinced that Catholics don't have to vote for only one party.

She admits she doesn't follow politics as much as she should. Like many of her friends, she plans to vote in November but will not caucus. The large number of Democratic candidates is "confusing," and the race's negativity is a turnoff for many young people, she said.

Muenster, who is president of Loras College Democrats, also sees her outreach to young voters as an uphill battle, especially on what she believes is a pretty conservative campus. "Based on what I've seen, people my age are very afraid to speak out and volunteer for a campaign."

Young people don't see themselves — or the things they care about — represented in politics, said Carlos Garrido, a senior at Loras who is involved with the campus' Labour Club, a de facto Bernie Sanders group.

"There is a lot of discontent and nihilism among younger voters," said Garrido, a Cuban immigrant from Florida who originally came to Iowa to play baseball at Clarke but transferred to Loras after an injury sidelined his athletic career. He is now planning to pursue graduate studies in philosophy.

He wasn't interested in politics until the Sanders 2016 campaign. "Bernie's basically preaching Catholic social teaching," Garrido says. "That's his whole platform: treating human beings with dignity, caring for God's creation, the preferential option for the poor."

Garrido credits his Catholic upbringing with shaping him politically, although he does not regularly attend Mass now. For him, being Christian is not just about going to church.

"It's also being active in the political arena and treating others as the embodiment of Jesus," he said.

Garrido — like others interviewed for this article — had little interest in a centrist Democrat such as Joe Biden, Pete Buttigieg or Amy Klobuchar. In fact, his second choice is Tulsi Gabbard, because of her opposition to foreign wars.

"People are tired of establishment politics, whether liberal or conservative," he said. "They want something new."

Political polarization

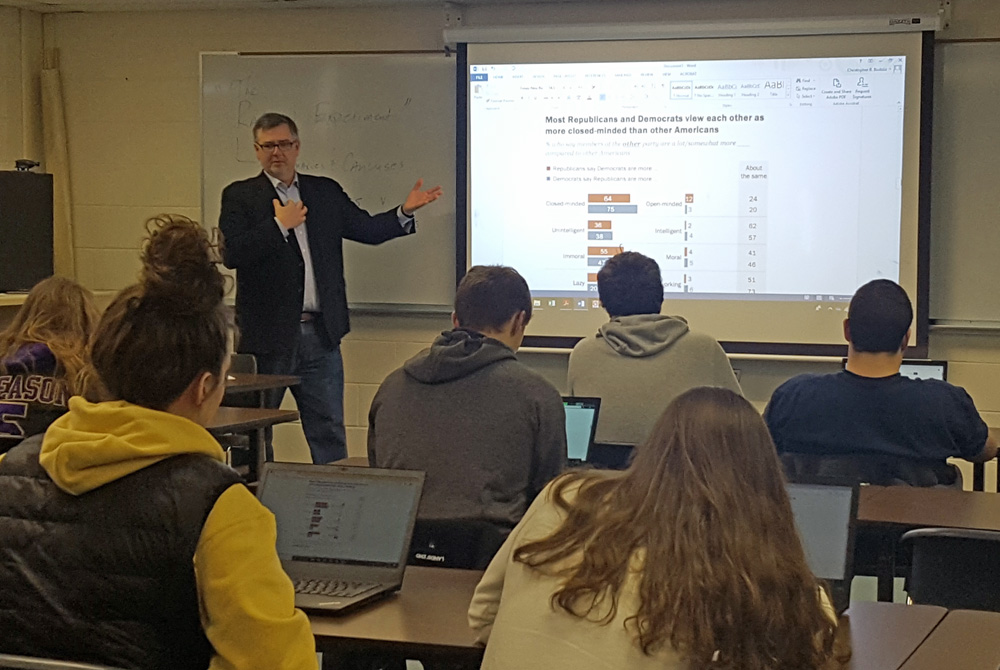

In a course titled "The Road to the White House," Loras College professor Christopher Budzisz is trying to get his students to think critically about the primary process and whether it contributes to partisanship and polarization, both within parties and more generally. His January-term course couldn't be more timely, as it meets the month before the Midwestern state's all-important Feb. 3 caucus.

Later, in an unofficial poll by show of hands, all of the students in the course indicate they plan to vote in the November general election, but only a handful say they will caucus, admittedly a longer, more-involved process.

They care enough about the election to have selected this course from all the others offered during J-term, but with more than a dozen candidates still running for the Democratic ticket at that point, they find it hard to select just one. The Republicans in the class, of course, already know who their party's candidate is.

But when Budzisz cites a poll about parents who are more disturbed by a child marrying someone of another political party than of another religion, the students perk up. Polarization among friends and potential dating partners hits home.

Loras College professor Christopher Budzisz teaches about the primary process just weeks before Iowa's Feb. 3 caucus in a course on "The Road to the White House." (NCR/Heidi Schlumpf)

Vigorous political debate is an everyday experience for roommates Darby Callahan and Conor Kelly, both students in the class who nevertheless model a civility not always found on the national stage, on social media or in some families.

Kelly, who writes an opinion column for the student newspaper where he has called for Trump's impeachment, favors Warren, in part because of her stance on disability rights. He suffered seizures when he was younger. Immigration and gun violence are other important issues to the Naperville, Illinois, native.

Callahan is a registered Republican whose family has farmed corn and soybeans on the same Iowa farm for 150 years. A business and marketing major, he wishes a GOP candidate would challenge Trump but admits the president has "strong support" in his home, despite the fact that many farmers are struggling financially under this administration.

Both young men attribute their political views — and the fact that they can coexist as roommates with different ones — to their faith.

Callahan describes himself as a "devout Catholic." He has been active in the pro-life movement, has attended the March for Life in Washington D.C. and supports his state's recently passed "heartbeat bill," which was found to be unconstitutional.

He said he's "really into social justice, too," but notes that "without the inalienable right to life, no other rights can exist."

Kelly, who wears a St. Christopher medal around his neck, admits has hasn't felt comfortable at church lately, in part because of Catholics who use abortion as a "litmus test for whether you are a true Catholic or not," he said.

"When I walk into the church, it's kind of hard — not because I don't believe in God, but because I feel there a bunch of eyes on me judging me."

Advertisement

Budzisz, an associate professor of politics, is not surprised that a number of Loras students credit their faith as guiding them in how they treat those with different opinions. "They have a sense that viewing the other side as somehow immoral or evil is not what Catholic voters are called to do," he said.

He also notes younger voters' attraction to "movement politics" that call for structural change. A number of students who attended a Andrew Yang event outside of class were inspired by his challenge to the status quo, "but in a way that is rooted in a moral understanding of how people are responsible to others," which appeals to the students' Catholic values, he said.

Cesar Vega plans to caucus for Yang because he believes he best addresses economic issues affecting people his age and those in more dire financial straits. During a social work internship, Vega has witnessed Iowans who live paycheck to paycheck.

"The GDP may be pretty high, but it doesn't reflect how we live every day," he said. "I see so many people in Dubuque who are struggling and think it's their fault, that they're not good enough. But it's really the system's fault."

A Chicago native and member of the college's Breitbach Catholic Thinkers & Leaders Program. Vega thinks the Democrats, in general, care more about the working class and are likely to support human rights, values he derives from his Catholic faith.

"As Catholics, we have to embrace everyone as our sisters and brothers," he said.

Although political participation of younger voters still lags behind older ones, Loras politics professor David Cochran thinks today's younger voters are actually more engaged — in part because out of frustration with the election of Trump. Certainly, they are visible canvassing across the state.

One poll of young Iowans (age 18-29) predicts a massive turnout on Feb. 3, with more than a third (35 percent) saying they were "extremely likely" to caucus and Sanders leading as the favorite by a wide margin.

Still, when Dubuque voters gather Monday evening to caucus — some right on Loras' campus in the Alumni Center — they represent a minority of voters, indeed, the most committed ones — of any age, Cochran said.

"It's a totally different electorate than we'll see in November."

[Heidi Schlumpf is NCR national correspondent. Her email address is hschlumpf@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter @HeidiSchlumpf.]