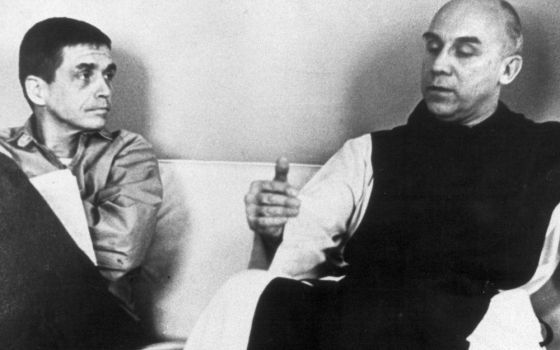

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, left, and Thomas Merton, at a retreat Merton hosted on spiritual roots of protest in November 1964. (Jim Forest)

"[Dan] will do much for the Church in America and so will his brother Phil. … They will have a hard time, though, and will have to pay for every step forward with their blood." — Thomas Merton

I was struck deeply, while reading Jim Forest's recent, well-written and insightful biography of Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, At Play in the Lions' Den, by one specific incident. After he was released from prison in February 1972, Dan moved into a Jesuit residence at Fordham University. Shortly thereafter, he returned from a lecture trip "to find the building locked, the lock changed, and his meager possessions in several boxes outside the entrance." He was understandably hurt and upset. He called his Jesuit provincial who told him to find himself an apartment in Manhattan and send him the bill.

Locked out seems like a good way to describe Dan's initial status in the Jesuits, one of whom claimed that Dan, as he wrote in his autobiography, To Dwell in Peace, was "in the order but not of it."

In the fall of 1957, he was appointed associate professor of New Testament studies at Le Moyne College in Syracuse, New York. After six years, Dan, who had been saying Mass in English facing the people years before the Second Vatican Council and had been doing inner-city activism in Syracuse and working for integration in the South, was given a yearlong sabbatical in France. He would never again hold a permanent or semi-permanent position on the faculty of a Jesuit institution.

"The satisfaction, achievement, devotion to study, the communality of faith with the young, these were gone," he wrote in his autobiography. "I lost my aura; more grievously, I lost a home. Henceforth I would be a wanderer on the earth, here and there, an overnight dwelling."

In November 1965, just eight months after we officially put ground troops in Vietnam, Roger LaPorte, a Catholic Worker, immolated himself in front of the United Nations Building. Dan's provincial, John McGinty, told him not to make any public statement about LaPorte's "suicide." Dan did speak positively about LaPorte, but at a private memorial service for the Catholic Worker community. There he argued that, whereas suicide proceeds from despair and loss of hope, LaPorte had died in another spirit where death is conceived of as a gift of life. However misguided the act, it was seen by Dan as an offering of self so that others might live. This thinly veiled reference to Christ's death infuriated his superiors. Berrigan was ostracized and quickly shipped out to Latin America by his Jesuit order.

After four months in Latin America, Dan returned to New York on March 8, 1966, now more determined than ever to do everything possible to end the war in Vietnam. In 1967, he and his brother Philip, a Josephite, became the first Catholic priests to be arrested for opposing the war.

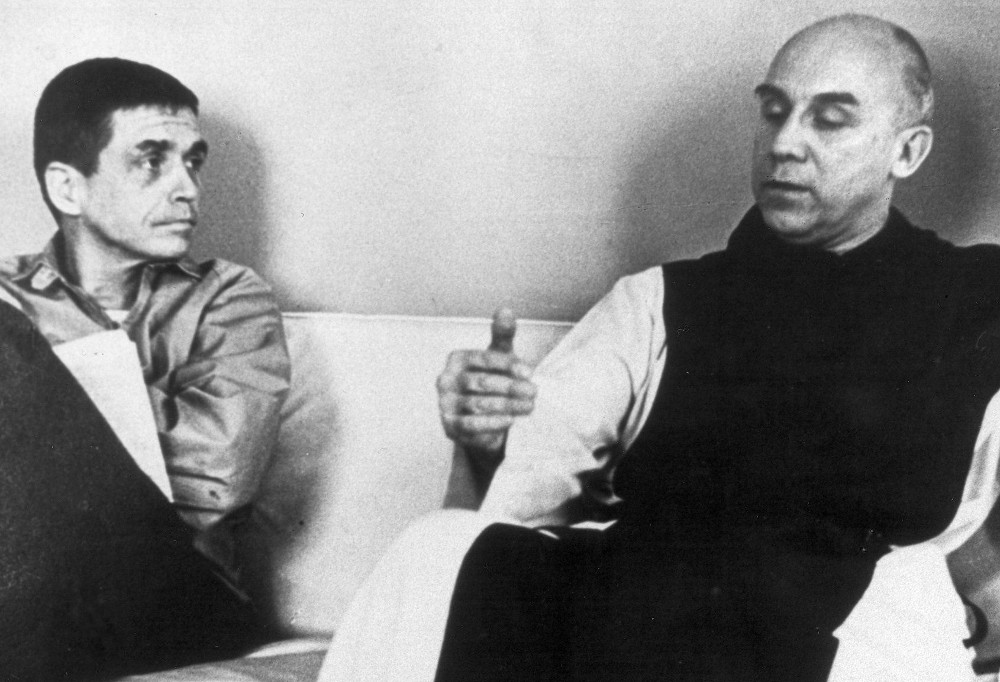

The Catonsville Nine burn draft records in Catonsville, Maryland, on May 17, 1968. (Newscom/Dennis Brack)

Then, on May 17, 1968, in an act that would change the nature of Christian nonviolent resistance forever, with eight others, Dan entered Local Draft Board No. 33 in Catonsville, Maryland. The participants seized Selective Service records (378 individual 1-A classification folders) and burned them outside the building with homemade napalm to make people understand "that killing others was repugnant to the letter and spirit of the Sermon on the Mount," he wrote. The trial of the Catonsville Nine, held in Baltimore Oct. 5-9, 1968, became a cause célèbre. Hundreds of people gathered at the courthouse every day of the trial.

Although Dan's fellow peace activists worked together for a common goal, not all agreed with the Berrigans' methods. Activist Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel did not practice civil disobedience and thought that going to jail was a waste of time. Catholic Worker co-founder Dorothy Day was a purely nonviolent protester who did not approve of the destruction of property. Although she acknowledged the disproportion between burning paper and burning children with napalm, she nonetheless maintained that "these actions are not ours." Like Day, Trappist Monk Thomas Merton espoused complete nonviolence. His fear was that violence against property might easily escalate to violence against people and that, in the long run, such actions might prove counterproductive. But the Berrigans stood their ground on the issue of violence toward "idolatrous things," maintaining that "some property has no right to exist."

In addition, this political activity isolated Dan further from his fellow Jesuits, some of whom, as already pointed out, locked him out of his residence shortly after he was released from prison after serving 18 months for the Catonsville affair.

"They [the Jesuits] almost kicked me into outer darkness after Catonsville," wrote Dan years later to his brother Phil, "[but I] was saved by…[Provincial Robert] Mitchell, who flew to Rome to stop the show." His law-breaking actions also alienated him more generally from both Catholic clergy and laity. The Catholic hierarchy supported the war in Vietnam. Generally speaking, Catholics were fiercely patriotic. They wanted to prove that there was no contradiction between being Catholic and being American. This emerged grotesquely in Cardinal Francis Spellman's infamous "My country, right or wrong."

Advertisement

The Berrigans challenged this unholy marriage between church and state, "the conjunction of soldiers and priests, the Red and the Black." Dan summed up the isolation he felt in a speech given in October 1973: "In America, in my church. … I am scarcely granted a place to teach, a place to worship, a place to announce the truths I live by." Fifteen years later, he was dismayed by the reception of his autobiography. "The W. St. Journal reviewed me with [Rev. Jerry] Falwell," he wrote to me, "two wackos for the price of one. So it went with the LA Times et al." He ended sardonically: "I must be doing something right."

Dan was doing many things right. He was locked out, to be sure, but he was also locked in of his own volition. He always considered himself an outsider within the Jesuits. He never quit the Jesuits, even during the LaPorte scandal when "it would have been easier to rid myself, once and for all, of a burden that had become an incubus," he wrote.

At that time, Merton encouraged him by suggesting, "Nothing but good can come to you from [your exile]." A few months later, when Dan was still thinking about the possibility of leaving the priesthood, Merton wrote, "We must stay where we are. We must stay with our community, even though it's absurd, makes no sense, and causes great suffering." Dan's sense of loyalty also ran deep: "I know how awesome a thing it was to give over one's life to a community. … I knew … that the bargain would not be reneged on: it was a stigma on my soul."

Slowly that community would open up to him. Forest notes that Dan moved into the West Side Jesuit Community in the mid-1970s and remained there until it closed in 2009. In 1987, Dan wrote in his autobiography: "only of late years, folded in a Jesuit community at last." In any event, it was Dan's first longtime home since joining the Jesuits and, according to Forest, "the great majority of those living [there] felt blessed to have Dan's presence, and it was mutual."

In 1985, Dan appeared with Robert De Niro and Jeremy Irons in "The Mission," a film about the Jesuit missions in Latin America in the 18th century. When asked why he chose to do so, he responded that it was "my best way of saying thank you to the Order for almost 50 years of undullness."

What emerged from the locked-out, locked-in situation? Did Berrigan's vision impact the church? What changes regarding war and peace took place in Catholicism during his time in the Jesuits?

Despite Pope Paul VI's Oct. 4, 1965, declaration before the United Nations General Assembly: "No more war, war never again. … You cannot love with offensive weapons in your hands," during most of Dan's time as a Jesuit, the church was comfortably entrenched in its "just war" theory. Let's not forget, for example, that, in November 2001, the U.S. Catholic bishops "voted 190-4 in support of the U.S. bombing of Afghanistan," according to Forest. But, a few months before Dan died in 2016, the Vatican hosted a global conference that called for Gospel nonviolence as a weapon to achieve peace and proposed that it was time "to bury the just war doctrine and focus instead on nonviolent methods of conflict resolution and what makes for a just peace."

When the war in Vietnam ended, Dan and others began to protest the existence of nuclear weapons. In their minds, this marked a passage from civil disobedience to divine obedience as expressed in Isaiah 2:4 — "They shall beat their swords into plowshares."

On Sept. 9, 1980, the first Plowshares action took place. Hoping to expose the criminality of nuclear weapons, the Plowshares Eight, Dan and his brother Phil among them, entered the General Electric Re-entry Division Assembly Facility in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania. Using hammers, they damaged two nuclear warhead cones of Mark 12A missiles and poured their blood on top-secret blueprints. Although this was Dan's only Plowshares action, he would for the rest of his life actively protest against the existence of nuclear weapons.

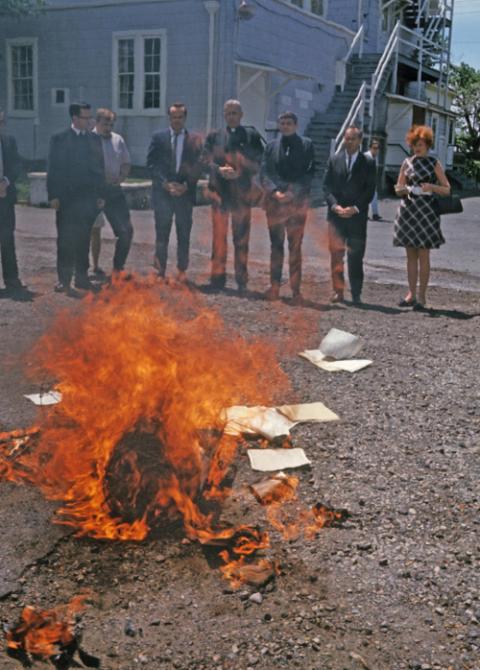

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, center, talks to a group of supporters outside the federal courthouse in New Orleans prior to his trail for contempt of court Feb. 8, 1990. Actor Martin Sheen; second from left, testified at the trial. (CNS/Clarion Herald/Frank Methe)

On this score, too, the church has evolved. In November 2017, Pope Francis declared: "Weapons of mass destruction, particularly nuclear weapons, create nothing but a false sense of security. They cannot constitute the basis for peaceful coexistence between members of the human family."

Coincidentally, the Nobel Committee wisely awarded its 2017 Peace Prize to ICAN (the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons), a non-governmental coalition of disarmament activists who campaigned for the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons that 122 countries adopted at the United Nations in July 2017. Not coincidentally, the Vatican was one of the first three countries to ratify it.

Ironically, it is Francis, the first Jesuit pope, who has moved the church from its longtime justification of nuclear weapons for purposes of deterrence — in 1982, Pope John Paul II affirmed that deterrence was "morally acceptable [as] a step on the way toward a progressive disarmament" — to the view that nuclear weapons must be dismantled. This new stance that "the very possession" of nuclear weapons is to be "firmly condemned" sounds much like the plea of another Jesuit, named Daniel Berrigan, uttered frequently many years ago: "Some property has no right to exist."

[Patrick Henry is Cushing Eells Emeritus Professor of Philosophy and Literature at Whitman College. He is the author of We Only Know Men: The Rescue of Jews in France during the Holocaust (2007) and the editor of Jewish Resistance Against the Nazis (2014).]