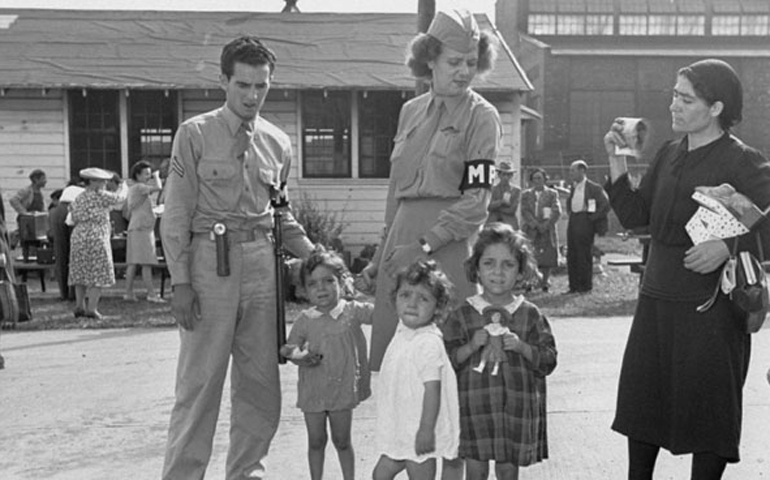

American military police help three little girls find their parents at the Fort Ontario Refugee Center in Oswego, N.Y., in 1944. (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

More than 70 years have passed since the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in April 1945, but the public controversy surrounding our 32nd president continues to intensify.

Roosevelt's critics claim that if he had utilized the full extent of U.S. power, many European Jews could have been saved from the mass murders carried out by Nazi Germany and its collaborators during the Holocaust.

FDR's supporters remind us that America was rife with anti-Semitism even during World War II, and while the president in 1942 was fully aware of Hitler's genocidal war against the Jews, Roosevelt believed the best way to save Jewish lives was a laser-like maximum military effort that would force Germany's "unconditional surrender" as quickly as possible.

Often overlooked in the public debate is the little-known story of how three American Christians serving as officials in FDR's Treasury Department led a successful effort to save 200,000 European Jews.

It began in December 1942, when FDR met in the White House with a group of American Jews headed by Rabbi Stephen Wise, at the time the most prominent Jewish leader in the United States. Roosevelt confirmed the horrific reports Wise and others had received about Nazi efforts to kill every Jew living under Nazi occupation:

"The government of the United States is very well-acquainted with most of the facts you are now bringing to our attention. Unfortunately, we have received confirmation from many sources. Representatives of the United States government in Switzerland and other neutral countries have given up proof that confirm the horrors discussed by you. We cannot treat these matters in normal ways."

FDR made no promises about any plan to save Jews other than winning the war. However, Wise kept demanding action.

In July 1943, Wise met privately with Roosevelt and proposed a novel program using bribery, creative diplomacy and courageous stealth to rescue Jews in Europe. To Wise's delight and astonishment, FDR replied: "Stephen, why don't you go ahead and do it?"

Roosevelt then called Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. and said: "This is a very fair proposal which Stephen makes." The Jewish Morgenthaus and the Episcopal Roosevelts were longtime friends and neighbors in Hyde Park, N.Y.

The U.S. government approved the project and authorized a payment of $170,000. But State Department officials, led by the anti-Jewish actions of Breckinridge Long, and the British Foreign Office delayed and sabotaged the program until Dec. 18, 1943.

Wise wrote that bureaucratic "bungling and callousness" prevented saving "thousands of Jewish lives."

A furious Morgenthau looked into the delay and discovered "the full extent of obstruction and double-dealing practiced by Long and his [State Department] cohorts."

But Wise's proposal to save Jewish lives accelerated within the Treasury Department. Protestant Josiah DuBois Jr. (1913-83), a Morgenthau assistant and a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Law School, prepared a comprehensive 18-page memorandum describing the tragic Jewish condition in Europe, as well as detailing the State Department's systematic pattern of blocking refugee immigration to the U.S. Only about 21,000 Jews were admitted to the U.S. during the war years, when the immigration quota was 191,000.

DuBois' memo, titled "Report to the Secretary on the Acquiescence of This Government in the Murder of the Jews," charged: "It is the policy of this Government to take all measures within its power to rescue the victims of enemy oppression who are in imminent danger of death and otherwise to afford such victims all possible relief and assistance consistent with the successful prosecution of the war."

A troubled Morgenthau was reticent to present the harshly worded memo to the president, but DuBois threatened to resign his position and expose the Roosevelt administration's anti-Jewish actions to the press.

Finally, Morgenthau reached the conclusion that DuBois' document must be given to FDR for executive action, but he gave it a more nuanced title: "Personal Memo to the President."

On Sunday, Jan. 16, 1944, Morgenthau; DuBois; Randolph Everghim Paul (1890-1956), the Treasury Department's general counsel; and another Treasury official, John Pehle (1910-90), met with FDR. Pehle, a Protestant, had a Catholic wife, and Paul stemmed from an 18th-century Quaker family.

The damning memo outlined the "incompetence, delay and even obstruction of a variety of rescue efforts" by the State Department. Morgenthau and his three associates believed the State Department was guilty of "acquiescence in Germany's mass murder of Jews."

Six days later, on Jan. 22, Roosevelt authorized the establishment of the War Refugee Board with Pehle as its first director and DuBois its general counsel. Pehle proved to be an effective leader and the War Refugee Board is credited with saving the lives of 200,000 Jews, as well as 20,000 people who were not Jewish.

Perhaps the War Refugee Board's most famous action was sending the Swedish businessman and diplomat Raoul Wallenberg (1912-47) to protect the Jews of Budapest, Hungary. His Nazi adversary in that difficult and dangerous endeavor was Adolf Eichmann, who was in Budapest at the same time. The skillful Wallenberg was able to save a significant number of Jewish lives, including Tom Lantos, who later served as a member of the U.S. Congress. The Soviet Army captured Wallenberg in 1945 and charged him with being a spy. It is believed he died in a Moscow prison in July 1947.

The War Refugee Board carried out other activities, and was one of the few positive achievements of the FDR administration involving Jews. But as Pehle later said, "I recognized that it was too late when it was established and the resources available were too small to deal effectively with the problem. But we were able to change the policy of the United States ... and we were able to change the moral position of the United States in this area."

Why did DuBois, Paul and Pehle give such extraordinary leadership to a rescue effort that was strongly opposed by the State Department and given somewhat tepid support by Roosevelt? Two scholars at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum provide some answers. Rebecca Erbelding, author of an upcoming book on the War Refugee Board, believes they acted out of humanitarian convictions, and Victoria Barnett credits "their faith" as a catalyst for the trio's efforts to save Jewish lives.

Whatever motivated them, DuBois, Paul and Pehle deserve to be remembered and celebrated in churches, synagogues, colleges and seminaries as members of a band of heroes and heroines we respectfully call "righteous gentiles."

[Rabbi A. James Rudin is the American Jewish Committee's senior interreligious adviser. His latest book is Pillar of Fire: The Biography of Rabbi Stephen S. Wise.]