Girls rescued from female genital cutting march through the streets of Suguta Marmar in northern Kenya to educate the community about the harms of the practice. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

Editor's note: This story is part of Global Sisters Report's yearlong series, "Out of the Shadows: Confronting Violence Against Women," which will focus on the ways Catholic sisters are responding to this global phenomenon.

(GSR logo/Olivia Bardo)

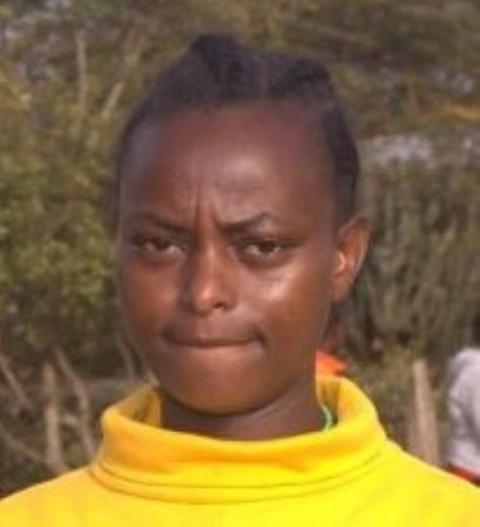

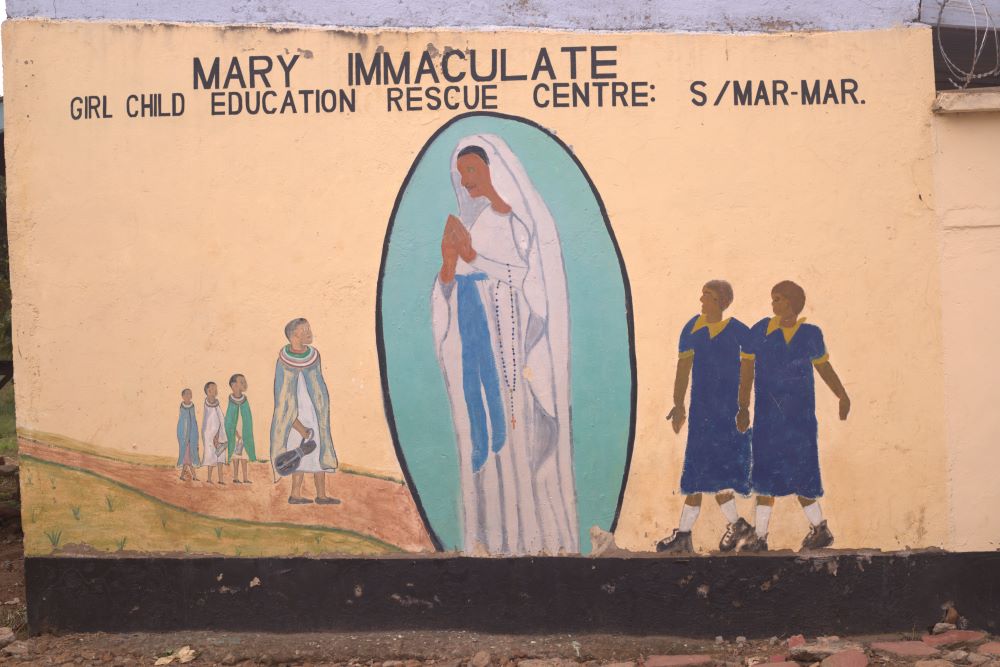

Seventeen-year-old Salome Naserian stands outside the chapel of the Mary Immaculate Rescue Center in this northern Kenyan town, her hands folded as a soft breeze carries the voices of girls rehearsing a song. The red Samburu earth and rounded hills around her are familiar landmarks, yet today marks a moment she once thought was beyond her reach.

She is preparing to graduate from a Christian Rite of Passage, an alternative ceremony created by Catholic sisters to replace female genital cutting, or mutilation. For Salome, this day represents not only a rite but freedom from a path she once believed was sealed.

She remembers the morning she discovered her uncle was preparing for her cutting, or FGC/FGM. Cooking smoke lingered as she overheard two women quietly discussing the visitor who would perform the ritual, the neighbor who would help hold her down, and the space behind the house prepared for the ceremony.

"I knew I had to leave," she said. "They saw it as something good. But I had seen girls suffer. I knew what would happen."

Samburu girls grow up with strict expectations: obedience, modesty and readiness for marriage. For generations, FGC has marked the transition into womanhood and defined a girl's value.

Seventeen-year-old Salome Naserian stands outside the chapel at the Mary Immaculate Rescue Center in Suguta Marmar in northern Kenya. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

Salome left Samburu without looking back, walking through dry shrubland until she felt safe. By evening she reached Suguta Marmar, a town known across the region for Catholic sisters who protect girls fleeing these harmful practices. A shopkeeper guided her to the police, who contacted the sisters.

For two years she has lived at the rescue center, returning to school and preparing for a ceremony that teaches girls that becoming a woman does not require pain.

"This rite is different from anything I imagined," she said. "We learn about ourselves, our faith and our future. We are shown that we matter."

Suguta Marmar sits deep in Samburu country, a region where the community has practiced FGC for generations. The practice is also common among Maasai communities, which share many cultural traditions with the Samburu. The ritual, often performed at dawn, is tied to ideas of purity, marriage readiness and community pride.

FGC involves partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs, for cultural and non-medical reasons. It can cause chronic pain, infections, anxiety, depression, birth complications and infertility, and can lead to death, according to the United Nations.

Although Kenya criminalized FGC in 2011, the practice persists in remote regions where cultural enforcement remains strong and law enforcement is limited.

Sr. Teresa Nduku, director of the Mary Immaculate Rescue Center, is pictured outside the center on Nov. 12. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

Historically, FGC exceeded 80% in Samburu, making it one of the most difficult regions in the country for intervention. Yet signs of change are emerging.

The 2023 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey shows the national FGC rate has dropped to 15%, down from 21% in 2014. For the sisters working in Samburu, the introduction of community-sanctioned alternative rites has opened long-closed doors.

"The change is small, but it is real," said Sr. Teresa Nduku, director of the Mary Immaculate Rescue Center. "Some fathers now bring daughters. Some mothers ask questions they never asked before. It is not happening everywhere, but it is happening."

The center currently houses 98 girls. Some arrived days before their scheduled cuttings; others ran from forced marriages arranged soon after the ritual. A few were brought by neighbors who feared what awaited the girls.

Mary's story of silence and escape

Among the girls preparing for the ceremony is 15-year-old Mary Leinkinye, whose journey to the center was far more dangerous than most.

Mary grew up in a remote part of Samburu where FGC often takes place at dawn, before neighbors or authorities can intervene. She remembers seeing girls in her village braided and painted with red ochre as relatives sang outside to distract them. Even as a child, she sensed the fear behind the forced smiles.

At age 10, her own turn came quietly. Older women called her outside one morning. She recalls the cold earth on her back, the hands pinning her down, and one woman urging her to be brave — although Mary did not understand what bravery meant in that moment.

"When they finished, they took me to a man's house," she said. "I had never spoken to him before. I did not understand why they said I was now a woman when I still felt like a child."

Shortly afterward, Mary was married off. She speaks sparingly about that time, but her silence carries the weight of what she endured.

Eventually she and a friend decided to run. They left at night, following goat trails across the dry grasslands, she said. They slept in trees, believing they would be safer above the ground. One night, a lion approached.

"My friend fell," she told Global Sisters Report softly. "The lion came. It took her. I could not help her. I climbed higher and stayed there until morning."

'This is not only about the cut. It is about how girls are seen. It is about who controls their bodies and their future.'

—Sr. Hellen Gathoni

Mary walked for three days, stopping only when exhaustion overwhelmed her, she said. Near Suguta Marmar, a woman found her and took her to a police station. Officers contacted the sisters, who traveled to bring her to safety.

When she first arrived at the center, Mary barely spoke. Over time, surrounded by patient counselors and girls with similar stories, she opened up. She enrolled in Grade Six and began participating in preparation classes for the alternative rite. She has been at the center for over a year.

"This place gave me peace," she said. "It helped me believe I could have another life."

A rite rooted in dignity

The Christian Rite of Passage is a weeklong ceremony designed to honor cultural traditions without harm. It mirrors the structure of traditional initiation ceremonies but replaces secrecy and pain with lessons on dignity, anatomy, safety, confidence and faith.

Girls learn that their bodies belong to them. They learn why FGC is harmful, how to recognize abuse and how to seek help. They are encouraged to imagine futures shaped by their own goals, not cultural demands.

Evenings at the center are gentle. Girls gather outside to share stories, ask questions and offer advice. Sisters join them, answering questions many never had space to ask.

Loreto Sr. Lucy Wambui, (far right) coordinator of the Termination of Female Genital Mutilation Collaborative Network, visits women who have abandoned female genital cutting in Suguta Marmar, northern Kenya. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

"The ceremony is not only about replacing FGM," said Sr. Hellen Gathoni. "It's about giving them a foundation to carry for life."

Graduation day brings parents, neighbors and local leaders to the center. Girls line up proudly as community elders offer prayers. Parents publicly promise not to cut or marry off their daughters — pledges once unthinkable in Samburu.

"When they make that promise in front of the community, it becomes something they choose with confidence," Nduku said. "It becomes a moment of pride."

The efforts in Suguta Marmar are part of a wider movement led by seven Catholic congregations. In 2022, they formed the Termination of Female Genital Mutilation Collaborative Network to coordinate training, pool resources and reach communities where individual congregations struggled alone.

Loreto Sr. Lucy Wambui, the network's coordinator, says collaboration has multiplied their impact.

"When we came together, everything expanded," she said. "We reached communities we had never reached before."

Central to their work is a 33-lesson curriculum developed by Sr. Ephigenia Gachiri, a longtime educator. The curriculum explores human development, dignity, womanhood and the body as a gift to be protected rather than harmed.

"Girls needed a rite that gave them understanding," Wambui said. "And families needed a transition they could embrace without feeling they were abandoning their culture."

The network also conducts outreach to boys and men, explaining the physical and emotional consequences of FGC — information many had never heard.

"When men learn, they change," Wambui said. "Understanding opens the door to acceptance."

Resistance and progress side by side

Despite progress, resistance remains strong. Some families still believe FGC prepares girls for marriage. Others fear their daughters will be ridiculed or considered impure if they are not cut. Cutters still operate at dawn or during school holidays, when girls are more vulnerable.

The Mary Immaculate Rescue Center in Suguta Marmar, Kenya, offers the Christian Rite of Passage, an alternative ceremony created by Catholic sisters to replace female genital cutting, or mutilation. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

Even among young men, opinions remain divided.

Twenty-five-year-old Shadrack Lekaingitele, a member of the warrior group for the Maasi people, said learning about the dangers of FGC changed his perspective.

"We have been taught that FGM hurts girls," he said. "It causes problems when they give birth, and many suffer. We must let our women achieve their dreams."

But others reject the shift entirely.

"I will not marry a woman who is not cut," said 23-year-old James Lengiteng. "My father says a woman who is not cut is like a man. Our children must be cut. Culture cannot be left."

Local administrator John Lekamparish enforces the law strictly. He said community surveillance and arrests have significantly reduced cases.

"In my area 90% of it is gone," he said, acknowledging that cutters often move to neighboring regions. "We are working with other local leaders to close those gaps. Slowly, this will end."

A global crisis with gender at its core

According to the United Nations Population Fund, more than 200 million women and girls worldwide have undergone FGCM. If current trends continue, 68 million more girls may be cut by 2030.

Advertisement

Experts describe FGC not only as a cultural practice but as a form of gender-based violence — tied to control over women's bodies, limited opportunities and expectations about marriage.

For the sisters in Samburu, confronting these norms is essential.

"This is not only about the cut," Gathoni said. "It is about how girls are seen. It is about who controls their bodies and their future."

Slowly, the narrative is shifting. Girls who once braced for the blade now hold certificates. Fathers who once insisted on cutting now clap proudly during graduation ceremonies. Mothers who feared social rejection now celebrate their daughters' education.

"There is no quick solution," Nduku said. "But every girl who comes through this center is a step forward."

As graduation begins, Salome and Mary take their places in line. The courtyard fills with song as community members watch quietly.

When Mary's name is called, she walks steadily to receive her certificate. For a moment, the weight of her past gives way to the promise of her future.

Salome stands beside her, smiling.

And as the ceremony ends, Mary offers a final reflection — both a plea and a vision.

"I want girls in my community to be rescued too," she said. "Because every girl deserves a life without pain."