Hunter Biden, son of President Joe Biden, speaks to guests during the White House Easter Egg Roll on the South Lawn of the White House, April 18, 2022, in Washington. (AP/Andrew Harnik, File)

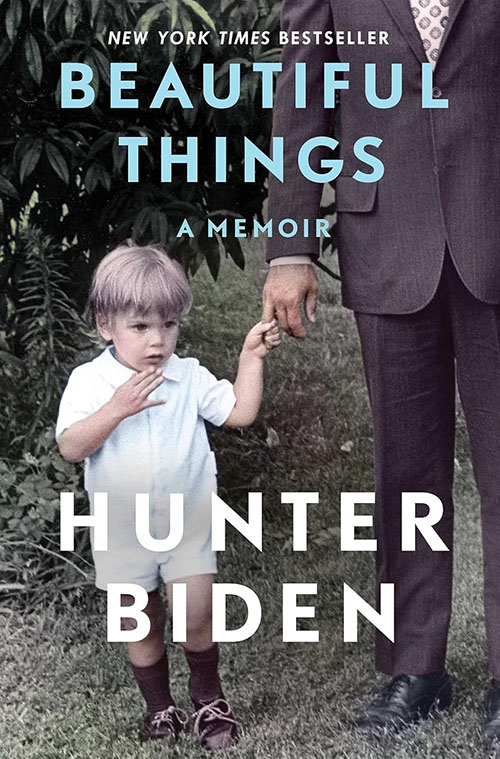

There has been one book that has shaped my view of integrating my faith with my political interest, and — unlikely as it may sound — it is Hunter Biden's Beautiful Things. When I first started telling this to close friends and my university classmates, they chuckled. "The oldest president in history's crack addict son? Have you completely lost it?"

That reaction is warranted. Hunter Biden himself admitted this strangeness. In the book's prologue he writes, "Mine is an unlikely résumé for this sort of confession. Believe me, I get it."

In the same way, I understand friends' reactions when I speak about how Biden's memoir touched me. His story is complicated in a way that news headlines don't communicate. But through reading Biden's own telling of the pain in his life with an open heart, I learned about the unrelenting grace that surrounds America's prodigal son.

Hunter Biden's life began with tragedy: He and his brother, Beau, were just toddlers when they were in the car accident that killed their mother and infant sister, Naomi. It was then that Biden encountered the prayer that would springboard his faith — which he would go on to clutch through the loss of Beau, through a divorce and through addiction.

He remembers learning the Hail Mary shortly after his mother's death, recalling, "[It] was the prayer my grandmother recited to me and Beau when she came into our bedroom at night to put us to sleep. She'd lie with us and scratch our backs while she told us about our mommy and what a wonderful and amazing human being she was."

Advertisement

Decades later, in the midst of addiction, he would call that prayer, "the only emotional anchor I still possessed."

This scenario struck me: a man who had just lost his last surviving full sibling, the one with whom he survived the crash that killed his mother and sister, sitting in a dark room, high on crack, compulsively repeating the Hail Mary. Biden wrote, "I couldn't stop repeating it. If I did, the pain of Beau's distance came flooding back."

The brothers were extremely close. Beau was a constant during Hunter's first attempt at recovering from alcoholism, accompanying Hunter to his first AA meeting and even finding his sponsor. When Hunter relapsed, Beau got him clean again.

After Beau died of glioblastoma, Hunter wrote him heartbreaking letters, some included in his memoir. One read, "Dear Beau, How do you expect me to be the one who's left behind? I don't know if I'm strong enough to do it. I don't seem to be doing anything but causing more pain by sticking around."

As a co-host of "Moby Pod" noted in their interview with Biden last month, Beautiful Things details earnest male intimacy in a way that is rare in today's hegemonic context. The love Hunter Biden has for Beau — and for their father — shines through in his writing.

At one point during his many discussions of Beau's character throughout the book, Biden recognizes he's rambling, stops, writes an ellipsis and tells the reader, "Wish you could've met Beau." I don't know if I have ever before read such authenticity from someone entrenched in the political sphere; it was as though Biden truly wanted his readers — wanted me — to know his brother like he did.

On Jan. 3, 1985, then-Sen. Joe Biden holds his daughter Ashley while taking a reenacted oath of office from Vice President George Bush during a ceremony on Capitol Hill in Washington. His wife, Jill, looks on and his sons, Beau (foreground) and Hunter, hold the Bible. (AP Photo/Lana Harris)

It was this combination of solid, embodied unconditional love and fervent prayer that led Hunter Biden to what I deem his "prodigal son" moment in 2019. At the invitation of his parents and in the throes of his ongoing addiction, Biden summoned the courage to attend what he believed to be a family gathering in Delaware. There, he was surprised to be met with his daughters (who flew in from college), his parents and two of his former counselors from a rehabilitation center, all of whom had gathered for a loving intervention. Unlike the parable in the Gospel of Luke, there was no older brother to react to the prodigal's return: Beau had already died.

But plenty of parallels remain. Biden recounts that in that moment, "[Dad] chased me down the driveway. He grabbed me, swung me around, and hugged me. He held me tight in the dark and cried for the longest time." Like the father in Jesus' illustration, President Joe Biden was just relieved Hunter came home.

In the Gospel of Luke, the prodigal says, "Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son" (Luke 15:21). Hunter Biden's own spirit of repentance would come later in the year, but come it finally did.

So when House Republicans ask repeatedly, "Where's Hunter?", it is moving to hear him respond, "I am here." Hunter Biden isn't shying away from his past; rather, he is openly sharing his story — one of coming home to be met with grace.