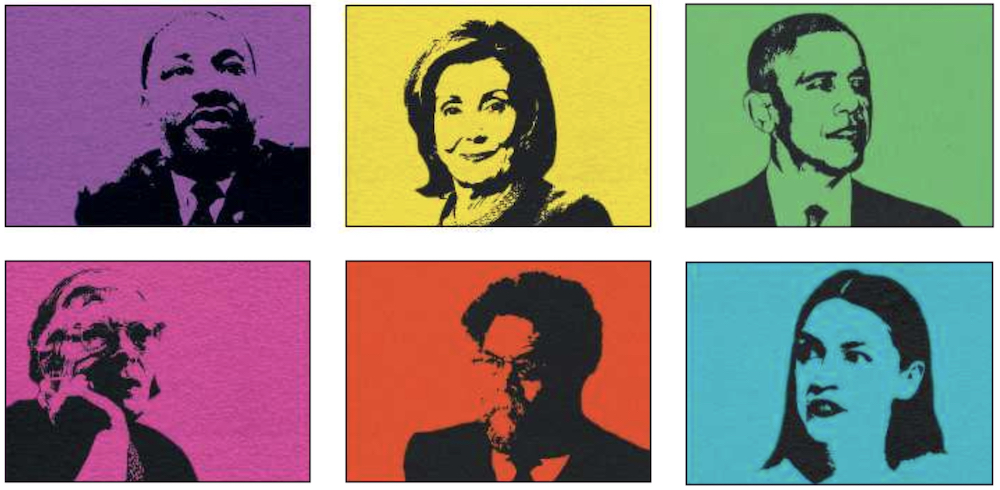

Top row, left to right: Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, former President Barack Obama; Bottom row: Dorothy Day, Cornell West, U.S. Rep. Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez (NCR digitally manipulated images/Wikimedia Commons, CNS)

A progressive Catholic activist told me years ago, "Jesus said to pray for our enemies. He didn't say we wouldn't have enemies." His point was that progressive Christians should not be sentimental about the Gospel or naïve about the realities of struggles for justice. I was reminded of his words as I read Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons' new book, Just Faith: Reclaiming Progressive Christianity.

Graves-Fitzsimmons began Just Faith in the aftermath of the 2016 election, and the alliance between President Donald Trump and the Christian right forms its backdrop. But where a number of Trump-era progressive Christian writings have promoted dialogue, bridge-building and encounter with conservatives to overcome political "division," Just Faith calls on progressive Christians to organize, fight and win.

To do that, Graves-Fitzsimmons thinks progressive Christians need to learn more about the history of progressive Christianity and the prevalence of progressive politics among Christians in the United States today. Too many progressive Christians, he says, think they are alone.

Graves-Fitzsimmons also wants progressive Christians to get comfortable talking about the relationship between their Christian faith and their progressive politics. He thinks many feel embarrassed to claim their faith publicly, as they do not want to be associated with the homophobia or sexism of the Christian right. But if progressive Christians reclaim their faith, he thinks, this will not only break the popular association between Christianity and anti-LGBTQ or anti-choice politics, it will also help progressives build political power and effect positive change.

In an effort to help progressive Christians understand their history and claim their faith, Graves-Fitzsimmons gives readers an overview of progressive and conservative Christian political history, shares and explains data on the prevalence of progressive Christians in the United States today, and addresses common obstacles to progressives speaking openly about faith and politics.

The book's discussion of history focuses on the 20th-century fundamentalist/modernist controversy in the United States. Graves-Fitzsimmons sketches the ways fundamentalism developed as a reaction against modernity. Fundamentalists emphasized biblical literalism and inerrancy, centered the atoning death of Christ, and insisted on strict and narrow doctrinal orthodoxy. Meanwhile, he writes, liberal Christianity developed in open dialogue with modernity. Liberal Christians embraced modernity — by accepting modern scientific discoveries, embracing the historical-critical method of reading Scripture and rejecting belief in miracles (for example, the literal bodily resurrection of Christ). In Graves-Fitzsimmons' view, this early 20th-century split is the root and the template of our contemporary intra-Christian disputes on LGBTQ inclusion, reproductive justice and other important justice issues.

Advertisement

Readers interested in statistics and social science research will appreciate the ways in which Graves-Fitzsimmons, a self-described data geek, incorporates statistics from the Public Religion Research Institute on the prevalence of progressive politics among U.S. Christians.

In the latter part of the book, Graves-Fitzsimmons addresses common obstacles to progressive Christians reclaiming Christianity. His discussion of Christians wanting to avoid "division" will likely appeal to activists and organizers. While he acknowledges that there are destructive forms of "division," he argues against the idea that division is inherently destructive or unChristian. Drawing on his experiences of activism, Graves-Fitzsimmons points out how the charge of sowing "division" has been used to dismiss oppressed and marginalized people fighting for justice.

Such a dismissal, he argues, also isn't consistent with Jesus' teaching and life. Jesus' ministry was not simply a ministry of reconciliation and social harmony. Jesus said, after all, "Do you think that I have come to bring peace to the Earth? No, I tell you, but rather division," including between father and son, mother and daughter. Following Jesus means working for justice, and that entails being at odds with principalities and powers, and even with our own communities and loved ones.

Yet there is also a significant limitation in making conservative versus progressive the division that frames the book's analysis of faith and politics in the contemporary United States. This binary largely obscures the substantial theological and political differences and divisions within those broad camps.

Pete Buttigieg, Nancy Pelosi, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Barack Obama, as well as Martin Luther King Jr., James Cone, Dorothy Day, Cornel West and Gustavo Gutierrez are all cited as examples of progressive Christians. Staunch proponents of capitalism alongside anti-capitalists, heads of the U.S. empire alongside liberationists, perpetrators of drone warfare alongside pacifists. To be fair, Graves-Fitzsimmons acknowledges that progressive Christianity includes people with political differences, and he cites the differences between just war theorists and pacifists as an example. He names the importance of criticizing one another.

But there are more than political or theological differences between many figures in the wide-ranging list above. By defining progressive Christians so much in opposition to the Christian right, Just Faith sometimes obscures the reality that liberationist Christians have not merely had to contend with powerful far right enemies like Pat Robertson or Donald Trump; they have faced powerful centrist and liberal enemies, too.

Just Faith is a passionate and accessible introduction for those who want to learn more about the connections between progressive politics and Christian faith. It will likely prove particularly encouraging to progressive Christians who believe — incorrectly — that they are alone.

[Kelly Stewart is a doctoral candidate at Vanderbilt University, where she studies trauma theory and Catholic theology.]