THE NONES ARE ALRIGHT: A NEW GENERATION OF BELIEVERS, SEEKERS, AND THOSE IN BETWEEN

By Kaya Oakes

Published by Orbis Books, 208 pages, $22

In a society that puts so much of a premium on data, numbers and analytics, it is easy to forget that statistics often do not tell us the whole story. Indeed, they often hide as much as they tell.

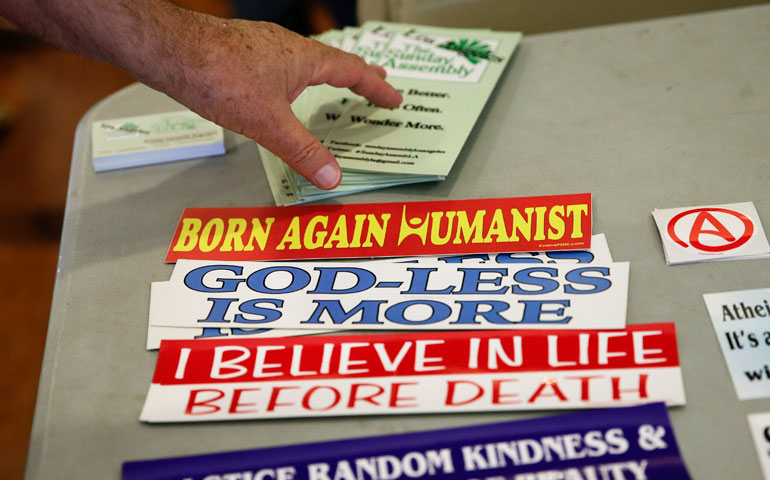

Such is the case with the emergence of the "nones," the catchall term for those who identify as agnostic, atheist, or unaffiliated with any particular religion. The nones now make up approximately one-quarter of the U.S. population and are growing in number. They are easily the most significant phenomenon in American religion today.

Many commentators have been concerned, if not distraught, with the increasing size of this demographic, resulting in general handwringing or calls for greater church outreach to bring these strays back to the flock.

Others have been more derisive, and have spoken of the nones in the same pejorative tone often reserved for millennials (there is much overlap between the two groups). The nones are accused of being morally shallow, vacuous, adrift and unwilling to accept the obligations of religious affiliation.

In all of these conversations, the focus seems to be on what is "wrong" with the nones. In fact, the problem is not with these individuals. It is with the category itself. The nones are treated as a static wedge of a pie chart or bar on a graph, a looming specter of unaffiliated gray. The title "nones" is a crude and clumsy classification that obscures far more than it tells. It is a label of negation that does a disservice to the seeking, struggling and creative renewal that composes the lived experience of those grouped under this name.

Thankfully, Kaya Oakes has given us The Nones Are Alright. As one who herself has experienced "drifting to the edges of faith," she takes us to the margins of religious affiliation to explore the category of "nones" and shows us just how complicated the whole truth is. Oakes has written widely about culture and religion, particularly among Gen Xers and millennials, and there are few better guides on these religious peripheries.

As she soberly reminds us, organized religion is often a fraught mix of promise and peril.

She poignantly writes, "At its best religion can provide a deep and abiding sense of consolation, thicken our sense of compassion, give us community, and provide narrative and structure. At its worst it can be a vehicle to making us to feel judged and condemned, it can break up our families, exacerbate political tension, and deplete our inner resources."

Starting in the first chapter of the book, she lifts the veil off of the term nones in the most constructive and helpful of ways. She demonstrates that younger Americans may be rejecting existing religious institutions, but they are most certainly not rejecting the journey. She shows that they, like most human beings, are seekers.

At the heart of the book are personal interviews with individuals that Oakes found through friends, family and social media. The chapters are thematically organized, looking at the diverse and fluid subgroups that can be found within the nones designation.

Through Oakes' narrative, the reader hears from nonbelievers; agnostics and atheists who still affiliate with organized churches ("belonging without believing"); those of mixed marriages who find themselves liminally between two or more faith identities; members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community who attempt to navigate the schizophrenic message they receive from many traditions; and women who struggle with the particular marginalization that organized religion often thrusts upon them.

The first half of the book includes an array of individuals from different faith backgrounds, including Jews, mainline Protestants, Buddhists, Muslims, and those weaving back and forth over the porous boundaries of multiple traditions.

The second looks more closely at Catholics, as the church has hemorrhaged younger women and men from Sunday pews. Oakes' emphasis stems from her own struggles with Catholicism, which she described in depth in her 2012 book Radical Reinvention: An Unlikely Return to the Catholic Church.

Her tensions with the church echo those of many other younger Catholics. These include the church's system of top-down leadership; its exclusions based on gender; its ambiguous, if not uncaring, attitude toward the LGBT community; and its overworked priests, who rarely have the time to address these concerns.

As a result, Catholics either leave the tradition altogether or become "Catholics in exile," those who, Oakes says, continue affinities for the tradition in spite of the institutional church.

Oakes brings the reader to individuals all over the country, from her Berkeley home to New York, back again, and many places in between. The book walks us through soup kitchens, university campuses, guerrilla worship services, and other arenas where the nones are building community, breaking bread and incarnating religious practices with one another outside institutional walls.

Into these personal stories, she weaves the larger discussions of context and demographics that have shaped the nones phenomenon; snippets of her own spiritual ebbs and flows; and general reflections on religion and culture.

The style is fluid, thoughtful and intimately personal. The reader shares in the joys, sorrows and doubts of those seekers who pass through the pages. Oakes amplifies her subjects' voices and their stories of spiritual journey. Those who read this book will find many instances that echo their own spiritual highs and lows.

A vein of institutional critique runs throughout, as the nones reveal the many ways in which existing religious institutions fall short.

As Oakes writes early on, "Religion often fails to meet us where we arrive, hauling the complex baggage of modern life. And, perhaps, many young Americans are culturally moving into a way of being beyond organized religion."

It is not a harsh indictment but a sober analysis. Entrenched institutions are more often responders than harbingers of change.

The Nones Are Alright shows just how little the term nones actually captures the phenomenon of change at hand. While others see the nones as a sign of decline, Oakes argues that we simply have not found a better word to describe what is taking place.

She is hopeful and open about what may come, writing, "What we see next as religion evolves could be completely surprising, unexpected, and beautiful." Indeed, the book is a reminder that we must not fear but embrace the margins. It is where seekers who find themselves outside existing institutions begin to build their own traditions.

As history has shown time and again, the margins are where the wellsprings of renewal begin to bubble up.

[Chris Staysniak is a doctoral candidate in American religious history at Boston College.]