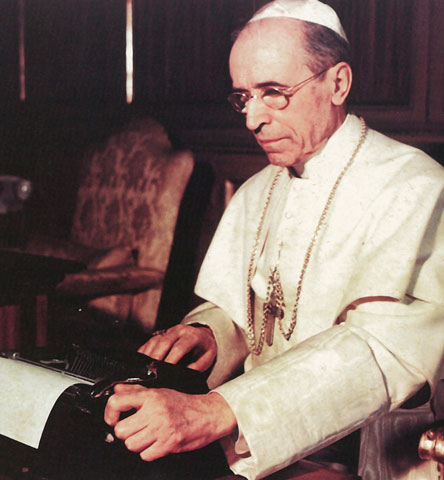

During World War II, Pope Pius XII writes one of his Christmas radio messages using a typewriter at the Vatican in an undated photo. (CNS/Courtesy of Libreria Editrice Vaticana)

SOLDIER OF CHRIST: THE LIFE OF POPE PIUS XII

SOLDIER OF CHRIST: THE LIFE OF POPE PIUS XII

By Robert A. Ventresca

Published by Belknap Press, $35

With Soldier of Christ, Robert Ventresca has provided a real service, not only to the historical profession but also to the wider community. Part of the story is well-known -- Eugenio Pacelli’s birth and early life in his native city of Rome, his poor health that necessitated his living at home while in the seminary, and his early education in canon and civil law. But Ventresca tells even the familiar parts of the story with such fluid strokes that one virtually feels the cobblestones under one’s feet as the young Pacelli walks the streets around St. Peter’s Square.

Except for his time in Germany, he spent his entire life within walking distance of his childhood home. His grandfather and father were members of the “Black Nobility,” the upper classes that remained faithful to the papacy after Italian capture of the Papal States, but while the family was comfortable, it was hardly wealthy.

Ordained in a private ceremony on Easter Sunday, 1899, Pacelli completed doctorates in canon and civil law. He was intent on becoming a parish priest when Cardinal Pietro Gasparri, secretary of the Congregation for Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs, convinced Pacelli to come to work at the congregation. Pacelli then went to the Academy of Ecclesiastical Nobles, the school for the Holy See’s diplomats and later assisted Gasparri as a minutante in drafting the Code of Canon Law promulgated in 1917. By that time, Gasparri was secretary of state under Benedict XV, and Pacelli was nuncio to Bavaria.

Sections of the Vatican Secret Archives opened to scholars in September 2006 enable Ventresca to reveal Secretary of State Pacelli’s reservations toward the Weimar Republic, especially its efforts to maintain a centrist government and the anger of one of the Catholic Center Party’s leaders, Heinrich Brüning (chancellor, 1930-32), toward Pacelli for urging compromise with Hitler to gain a concordat with the government.

Ventresca deciphers the spidery handwritten accounts of Pacelli’s almost daily interviews with Pius XI, which disclose an emerging Vatican policy of leaving it to bishops in countries undergoing persecution to determine the best course of action against government abuses. Therefore, Pacelli and/or the pope accepted the request that the pope issue an encyclical against Nazism from five leading German prelates, including three cardinals. Pacelli’s hand can be easily discerned on the document that developed into Mit Brennender Sorge, published in March 1937. This did not mean, however, that bishops, or even cardinals, were free to pursue their own agenda independent of the Vatican. For instance, in an episode that the author passes over, Cardinal Theodor Innitzer of Vienna initially welcomed the Anschluss in March 1938, called for Austrian Catholics to vote for it in a plebiscite, and even signed a letter to the local Nazi leader with “Heil Hitler.” Pacelli summoned Innitzer to Rome, where he had to change his position, for his action undermined what the German bishops were doing.

The war years have caused the most controversy over Pope Pius XII. He did seem to rely too much on diplomatic exchanges and received conflicting advice from some bishops. Like his predecessor Pius XI, Pius XII relied too heavily on concordats, agreements between the Holy See and a government that guaranteed the rights of the church and its members, but did not give the church rights to intervene in the treatment of non-Catholics, as the German church would discover in regard to Jews.

Part of the problem in evaluating Pius XII and his attitude toward the Jews is one of papal rhetoric. Pius would not sign a statement of the Allies condemning Nazi atrocities in December 1942 because it did not mention atrocities of the Soviet Union, one of the Allies. Instead, in his Christmas address that year, he alluded to “the hundreds of thousands of persons who, without any fault on their part, sometimes only because of their nationality or race, have been consigned to death.” To the pope -- and, incidentally, to the Nazis -- this was a clear denunciation of Nazi policy toward Jews. To later generations, however, it was not so clear, but represented “Vaticanese” that preferred generalities to specifics.

Many people, including historians, see a sharp theological break between Pius and his successors. Ventresca, however, points to some of the new theological directions of Pius that would lead to the council. The pope issued three encyclicals during the war: Divino Afflante Spiritu, on the study of Scripture; Mystici Corporis Christi, on the church as the mystical body of Christ; and Mediator Dei, on the liturgy. Each of these documents would pave the way for the Second Vatican Council. But the author also notes the retrenchment that began to take place with Humani Generis in 1951.

In his conclusion, Ventresca suggests that the pope could have done more for the Jews during the war. The pope was not anti-Semitic, but lacked the bold witness to the Gospel that Jacques Maritain, the French philosopher and postwar ambassador to the Holy See, called for. Pius many times did act more the part of a diplomat than the supreme pastor.

As Ventresca points out, the pope admired the German people and certain aspects of German culture -- the pope made Mother Pascalina Lehnert, who had worked for him in the German nunciature, the head of his Vatican household and chose two German Jesuits, Robert Leiber and Wilhelm Hentrich, as his confidantes and a third, Augustin Bea, as his confessor. This did lead him to repudiate the Allied policy of assigning collective guilt to the German people, but in this he was not alone.

Ventresca makes every effort to be objective and balanced in his presentation of the controversial wartime pope. In this, he makes a refreshing and needed contribution to what has become a sometimes rancorous debate, which has more assertion of opinion than serious archival research. The author basically sums up his evaluation of Pius XII by citing a remark attributed to Leiber that Pius was a great pope, but not a saint.

[Historian and author Jesuit Fr. Gerald P. Fogarty is the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Religious Studies and History at the University of Virginia. His fields include American Catholic history; Vatican-American relations; history of Catholic theology since the French Revolution; and the history of Vatican II.]