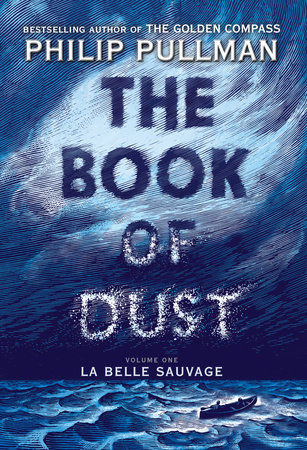

La Belle Sauvage is the protagonist's canoe in "The Book of Dust." (Unsplash/Alasdair Elmes)

It has been 17 years since Philip Pullman released The Amber Spyglass, the third in the His Dark Materials trilogy. I have read each book so many times that the copies should be tattered and worn — only they're not because I've given them away as often as I've read them and then bought new copies for myself so that I can read them again. I can't help it. I'm a Pullman proselytizer.

And I'm not alone. His Dark Materials has sold more than 17.5 million copies around the world. In 2002, it even outsold Harry Potter in bookstores in the United Kingdom. Books have been written about these books. They have been adapted for stage and screen. And the protagonist, Lyra, has entered the ranks of those characters who are known, and known well, by one name. Puck. Frodo. Aslan. Lyra.

Like the alethiometer, the golden, truth-telling compass introduced in the very first book, the levels of meaning get deeper with each read of each book. These are adventure stories, enthralling fantasies with bear kings and witches. They are coming-of-age stories, stories of friendship and love. They are stories about the danger of dogma and the threat of theocracy. They are stories about original sin and about consciousness. They are stories about what it means to be human and what it means to be divine and what it means to be both.

In this newest installment, The Book of Dust: La Belle Sauvage (The Book of Dust, Volume One), the levels of meaning seem closer to the surface. Maybe that's because we are experts by now, having traveled through this world for hundreds of pages. Or maybe that's because this is a more focused, more grounded story. In this book, along with adventure and fantasy, we get a fairy tale and a spy thriller. And while the first three books were spiritual and ethereal, this one is almost strictly material, Earth-bound.

In this book, our hero is a boy named Malcolm Polstead. Malcolm, as Pullman described, is "liked when noticed, but not noticed much." He works at his family's inn on the Thames, and he is happiest in his canoe, the titular La Belle Sauvage. Malcolm's curiosity is piqued when three important men come to the inn asking about a baby living at the priory across the river. The baby is Lyra. And when a flood and a madman threaten Lyra's life, Malcolm and his friend Alice hop in his canoe and do everything they can to protect her.

Pullman has been working on this book for years. Yet it speaks to this moment. It is strangely prescient. At points, it almost reads as a cautionary tale for today's Brits and Americans as we're confronted with nationalism and populism teetering on tyranny.

"It wasn't an easy time; everything seemed hung about with an unhappy air of suspicion and fear," Pullman writes. Sound familiar?

There's a war going on in Malcolm's world, a cold-ish war. The Magisterium, which is like the Catholic Church during the Spanish Inquisition or worse, is on one side. Oakley Street, a secret service apparently inspired by John le Carré, author of Tinker Tailor Solider Spy, is on the other.

The Magisterium is promulgating ignorance, fear and absolute power — which, as we know from the 19th-century British politician Lord Acton, "corrupts absolutely" and certainly does in these pages. Oakley Street is fighting for knowledge, courage and liberty — even if that means going down a paradoxical path. As one of Oakley Street's top brass explains to Dr. Hannah Relf, Malcolm's mentor and an increasingly witting and willing accomplice in the war: "We can only defend democracy by being undemocratic."

Advertisement

But the battle is over democracy itself. Secret arrests and imprisonments are commonplace. Habeas corpus and freedom of speech have no place. The Consistorial Court of Discipline — "an agency of the Church concerned with heresy and unbelief" — is fueling terror. Children are being recruited as informants. It's an authoritarian nightmare.

As with the first three books, we are not in Narnia here. We are far from it. There is no Christian allegory to be found, just one big, flashing red light to warn us about what happens when organized religion runs amok. Although in this one, we do get a glimpse of the good nuns, along with the bad.

Unlike the first three books, and despite its title, this one doesn't focus on Dust. At least not overtly. Or maybe I just need to read it a few more times to get there.

Dust, which Pullman describes as an "analogy of consciousness," really drove Lyra's story. In her world, as in Malcolm's, humans are accompanied by daemons, the animal embodiment of themselves. The daemons are fixed at puberty, but until then, they change — from leopard to greyhound to mouse and so on.

In the first book of His Dark Materials, the church's scientists, who believe Dust to be related to original sin, conduct horrible experiments to find out why Dust is more attracted to humans once their daemons are fixed. The second book takes us to other worlds to find the source of Dust. And only in the third book do we start to really understand it.

In this book, set before those three, the madman who chases after Malcolm, Alice and Lyra is an expert on Dust. Scientists are studying it where they can without being found out. And the church is concerned about it. But beyond a good explanation of consciousness as possibly material, not spiritual, we don't learn much more about it.

Still, I'm hopeful that in the next installment, which Pullman has already completed, we will. Pullman has promised that this new trilogy, set against the backdrop of this battle between freedom and despotism, will continue to take on the question of Dust. In a recent interview, he said, "It's the question of consciousness, perhaps the oldest philosophical question of all: Are we matter? Or are we spirit and matter? What is consciousness if there is no spirit?"

But this first book — similar to, perhaps, Dust itself — is material, not spiritual. And in the end, while Malcolm keeps Lyra safe, the flood-ravaged, tyranny-ridden nation is anything but. So there are more adventures to come.

Like La Belle Sauvage, there is wild beauty in this book. And like the floodwaters, it picks up speed as the tension rises. It was well worth the wait, and it is well worth the read.

[Kate Childs Graham is a speechwriter and communications strategist in Washington, D.C.]