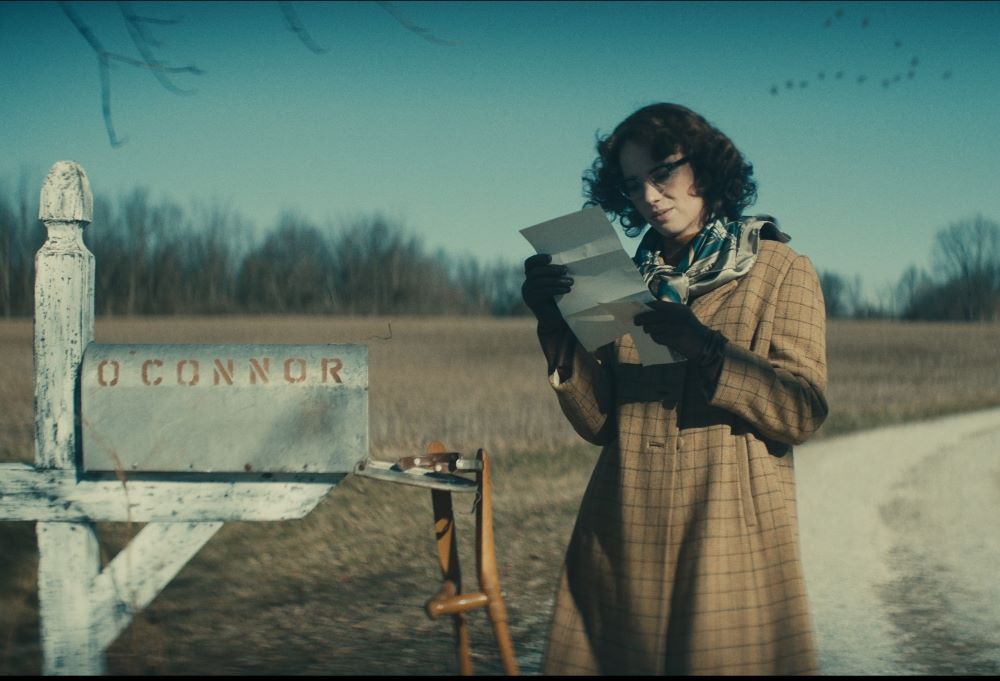

Maya Hawke portrays the Southern Gothic writer Flannery O'Connor in "Wildcat," directed by her father, Ethan Hawke. (Courtesy of Oscilloscope)

When director Ethan Hawke and fellow writer Shelby Gaines set out to make a film about Southern Gothic writer Flannery O'Connor, they knew that whatever they made would not be a straightforward biopic.

For starters, Hawke's daughter, Maya Hawke ("Stranger Things"), would be playing O'Connor, turning "Wildcat" into a family affair. Second, while O'Connor's inner life and imagination was vivid and vibrant, by her own accounts her quotidian rhythms were far from cinematic. Unable to travel due to lupus, she spent the majority of her years at her family home in Baldwin County, Georgia. "All she did was write, feed the chickens and go to church! There’s really nothing to say," Hawke joked to NCR.

Yet Hawke found much cinematic potential in exploring O'Connor's inner life. He noted how short stories such as "Good Country People," "Revelation" and "The Life You Save May Be Your Own," written at the height of her illness, were the ways she processed her own questions about God, faith, sickness and the body. Hawke and his crew set out to make a film that was not just about O'Connor's life, but about the role of faith in the artistic and creative process.

"Wildcat" weaves together the events of O'Connor's life with reenactments of some of her short stories. This fluidity that blurs the lines between fact and fiction ultimately points to what makes O'Connor's writing so transcendent and resonant to this day.

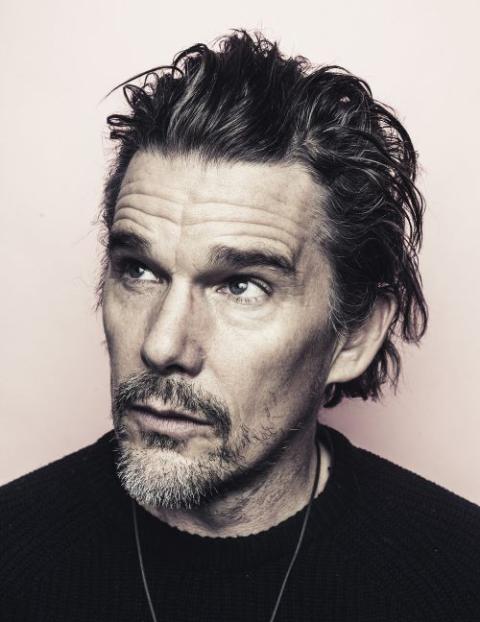

Ethan Hawke directs "Wildcat," a film about the writer Flannery O'Connor. (Courtesy of Oscilloscope)

Over Zoom, Ethan Hawke spoke with NCR about the process of picking which short stories to feature, the difference between art that proselytizes and art that's invitational and the influence writers like Julian of Norwich and Thomas Merton have had on his own creative process and faith.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

NCR: Your mother was Episcopalian and was your first introduction to Flannery O'Connor. Your daughter, Maya, grew to love O'Connor on her own and used A Prayer Journal for her Juilliard monologue. What was it like to create this film when both of you have close attachments to O'Connor's writing?

Hawke: I think with any great writer people form individual attachments. There are certain things that draw each one of us to writers that we love. For me, I think what was beautiful about building the movie was connecting these two very different relationships in my life. One is to my mother and one is to my daughter. I was in conversation with both of them while making the movie.

My mother loved a lot of the great Catholic writers of her era, such as Walker Percy and Thomas Merton. She was always giving me these books and from an early age was wanting me to engage with some of the best spiritual writing of her generation. When I had Maya, she discovered O'Connor's work on her own and was the one who first brought O'Connor's A Prayer Journal to me. It lent a different kind of insight into O'Connor's work. That really hypnotized Maya.

There were really three relationships to O'Connor that we had to balance while making this film. On the one hand, you have Maya who was coming to this project with this young person's energy and on the other, I had my own relationship to the text and was also bringing my mother's relationship with it. It was wonderful.

The Southern Gothic writer Flannery O'Connor is seen in this 1962 photo. She and her short stories are the subject of "Wildcat," directed by Ethan Hawke and starring Maya Hawke. (CNS/AP/PBS)

So from the very beginning, "Wildcat" was going to be a project with interwoven stories and perspectives. How did you come to the decision to use O'Connor's short stories as direct parallels to some of the hardships she was going through in her own life? How did you decide which ones to pick?

When Maya came to us with the desire to make a film about Flannery O'Connor, Shelby and I decided we would start the script process by just reading all of O'Connor's stories. One of the things that was very obvious was that regardless of the final form of the film, it was going to focus on the inner life. She's quoted as telling people that she'll never have any biographers because her life is too boring. All she did was write, feed the chickens and go to church! There's really nothing to say.

I heard that and laughed. I remember saying "That’s not true … not if we make a biography about the life of the mind." Her inner life was exceptional. Shelby and I knew right away that you can't make an ordinary film about an extraordinary person. The way she thought and the way that she approached art is so different from the way most people do … it would be criminal to just try to make an ordinary movie about her. This idea started to float to the top for us: What if "Wildcat" was a movie not just about imagination, but about the place where faith, imagination and reality intersect? O'Connor is an incredibly interesting subject matter if that is your thesis and starting point.

I liked the idea of having Maya and Laura (Linney) play versions of O'Connor's characters. O'Connor's primary relationship in her life, if not to God, was to her mother. As I started reading more of O'Connor's stories, I started seeing her mother almost appear as different characters in those stories. She was dressed differently and appeared in different cities, but she was definitely present. Stories that exemplified that became Shelby's and my criteria for which stories to pick in this film. We wanted to pick stories that fleshed out a different dynamic between the mother and daughter. It wasn't about which stories were our favorites … it was about which ones would unlock the mystery of Regina and Flannery.

On a visual level, your film captures how reality quite viscerally informs what an author writes. We see some of this in the film when Flannery notices a man without an arm in the train station she's waiting at and she includes a character that has no arm in a short story. Is that sort of how you approach creative work too?

So much. I live so much of my life in my head. I’ll be looking at the Cubs game and imagine if it was a movie. Or if I'm at the airport I'll think, "What's the film version of this? Who would be directing this film? What style will it be in?" My mind is always doing that.

Writer-director Ethan Hawke, left, and his daughter, actor Maya Hawke, talk on the set of "Wildcat," which draws from the short stories of Flannery O'Connor. (Courtesy of Oscilloscope)

Seeing the arc of O'Connor's life unfold on screen made me think of this 15th-century mystic, Julian of Norwich. Are you familiar with her at all?

"All shall be well! All shall be well! All shall be well!" Yeah, I love her!

I thought about Julian's words and story while watching "Wildcat." She, too, came to encounter God out of physical need. Her faith took on an embodied form. How have you come to think about the body and the physical as it relates to faith?

Flannery had this term called "diminishments." She shared that as you lose your health, you experience these diminishments. But these are gateways to gratitude. Many of us don't see the gifts we're given because we take them for granted. As Flannery stopped being able to walk, she started realizing that she didn't express gratitude in the past for waking up in the morning and being able to walk. There were so many things that were taken away from her because of her sickness. She loved to travel but that too was taken away from her.

But as her sickness carried on, she realized she didn't need to go anywhere. There's that line in the film where she says, "The kingdom of God is in the midst of you." That sentiment was very important to her. She held to this notion that everything that's real is actually right here in ourselves.

The body is this organism that reminds us of this reality. She often has characters who have one leg or are missing a hand or don't have vision. She's trying to remind readers of their humanness, that this flesh is not the sum of who we are. Your eyes are not you … your hand is not you. This leads you to the question of "OK, what is me?" That's a very exciting and possibly revelatory question.

Let's talk about the lighting choices for the film. In those scenes where you bounce between reenactments of O'Connor's work and what's going on in her personal life, they seem to be lit similarly, so it's almost like there's no aesthetic distinction between the two.

This was a very difficult project to wrangle for us, particularly for the audience. If your thesis statement is that the inner life is real, then you can't do a "Wizard of Oz" trick where you show reality is in black and white and imagination is in color. By doing that you're saying they're different things. So, what we tried to do with lighting is make sure that the camera didn't move during all those scenes that are involved with her real life. In contrast to the scenes of her short stories, her real-life scenes are shot in long takes and lack primary color, but it's all the same lenses and color palette of those scenes of fiction. We would let ourselves play with lighting and camera moves to show that imagination and reality are the same thing.

A scene from "Wildcat," directed by Ethan Hawke and starring Maya Hawke. (Courtesy of Oscilloscope)

For O'Connor, writing was such a cathartic experience, a "plunge into reality" and the difficult part came when she had to advertise her work. Making "Wildcat" was such a personally enriching and fulfilling experience between you and Maya — but the marketing and publicity is harder. Will self-promotion always be the price creatives have to pay when making art for the public, or do you think there's a better way?

When I was a kid growing up, a new Jack Nicholson movie would come out and he didn't do any interviews. Robert De Niro, Paul Newman, Robert Redford … they'd rarely go on talk shows. They were very withholding with their public appearances.

Now with social media and the way the internet works, whether you're a musician or an actor, you have to be an advertising agent. Especially for anything that doesn't have a big budget, the only way to try to reach people is the way that you and I are doing it right now.

It's very challenging on the artists because it forces you to come up with pithy little statements that define the movie or define the performance. I think all of us would love to avoid having to anecdotalize our lives. You're basically coming up with advertising slogans. It makes everything smaller, and it turns it into a unit of sale.

One of the things that's happened during the course of my lifetime is movies have been usurped by big business people who've discovered that human beings love film. It's a very easily digestible artistic medium. It's a lot easier to watch "Game of Thrones" than it is to read War and Peace. I would find it so funny that when "Game of Thrones" was so popular, there would be these huge cliffhanger episodes where everyone would wonder what's going to happen to a character. I was always like "Read the book guys. I can tell you exactly what's going to happen." But nobody wanted to do that.

Our relationship to literature is changing our relationship to what we expect from movies. We expect movies to tap dance, juggle for us and entertain us completely. I felt like when I was younger, there was always a place for that kind of commercial film. But audiences would also try to go to films that were more challenging and would try to engage you in a conversation. I always found those movies more interesting. But also, I live with movies. A lot of people see only a couple movies a year and so they want it to be "Raiders of the Lost Ark." I understand that. I'm not sure if that answers your question (laughs).

Advertisement

You've cited that one of the things you love about O'Connor's work was that she doesn't proselytize. Her work deals with matters of faith, but in her writing, she's not trying to convert you; it takes an invitational posture. Where is this line for you between art that proselytizes versus an art that invites people to wonder and taste something of the divine?

I could write an essay on that question. That is the great question because I love work that invites me to a more serious conversation. I have been amazed that while O'Connor says she wasn't proselytizing, there are so many people who converted to Catholicism from reading her. I think it's because she's not trying to sell you anything. She's showing you by example, a life of great faith and great devotion can lead you to depth of insight.

It's a big conversation about what's invitational versus what is not. Simply put, I'd say art that glosses over the pain of life ends up feeling like you're preaching to the choir. I'm paraphrasing the line we put in the movie, but "people want religion to be a warm electric blanket, but really, it's the cross." That's a very powerful statement. The cross is an extremely powerful and dark image to be the central image for one's faith. It's an admission of suffering. I think that the serious invitational art really accepts suffering and sees the value of powerlessness versus championing power. Proselytizing art says, "If you're good, God will give you lots of money and lots of status." That kind of art is not seeking the insight that comes from a life of devotion.

That kind of insight gives you the ability to handle any set of circumstances, whether positive or negative, because you realize it's all positive. It gives you perspective, so that way you can be grateful when you're suffering because you know you're growing. When you're not suffering … hey, thank God (laughs). We're presented with a win-win situation. We just don't often see it that way.

Thomas Merton has made an appearance now in two projects you're involved in, "First Reformed" and "Wildcat." Merton wrote that there are levels to one's prayers. Often we stay in a certain mode of petitionary prayer, but there's something transcendent when our inner life moves into something more transformative. I wonder if you see Merton's views on prayers as a helpful analogy for creative work.

I really do. What you're talking about is contemplation, which is what Merton wrote so much about. It's a hard word to really define. He was a big part of my life. I read The Seven Storey Mountain when I was 22 and it was very powerful for me, and woke me up to reading a lot of things. Richard Rohr right now is a thinker in the same vein who is talking about contemplation and how the real value of prayer is a deeper form of meditation. He's kind of guiding his congregations to think more deeply about the universe that surrounds us.

When you hold onto that greater perspective in the creative process, it starts to liberate you from your own peculiar wants and desires. That feels wonderful when you can start to see yourself as part of a larger brother and sisterhood.