Sisters and staff of Milwaukee-area religious communities tour Full Circle Healing Farm, a community farm dedicated to racial and food justice operated by Martice and Amy scales. Martice has been active in national advocacy for a Farm Bill that prioritizes land access for BIPOC farmers. (Pat Robinson)

When Tela Troge, a member of the Shinnecock nation, responded during a webinar April 5 to the Catholic Church's recent repudiation of the Doctrine of Discovery, she recalled learning about the doctrine as a new law student in 2010. "It's just so ingrained in our everyday life. Everytime we enter into a real estate transaction, there's theft and enslavement of Indigenous people implicit in that, and in the whole foundation of American property law," she said.

In her first property law class, Tela was introduced to the 1823 Supreme Court case Johnson v. M'Intosh. Regarded as the foundational case in American property law, it ruled that Indigenous people cannot hold title to land, citing that "discovery is the foundation of title in European nations, and this overlooks all proprietary rights in the natives."

That language is lifted from the Doctrine of Discovery, a set of 15th-century papal decrees that authorized European nations to conquer non-Christian lands and people. The Vatican's recent repudiation of the doctrine is a significant step in healing and reconciliation, but it will only be truly powerful if it changes our beliefs — and actions — about "property."

The Catholic Church is the largest private landowner in the world. In a moment when many dioceses and other Catholic institutions are divesting of property and downsizing, Catholic decision-makers can model a true ethic of repudiation through acts of land return, rematriation and land reparations.

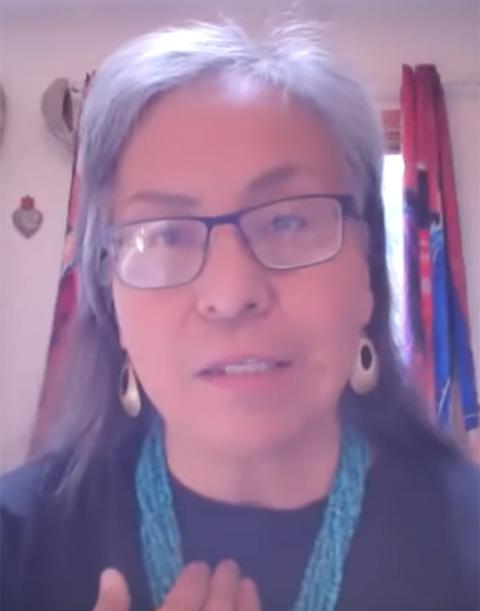

As part of a 2022 Assembly of First Nations delegation to the Vatican, Michelle Schenandoah presented Pope Francis with an empty Haudenosaunee cradleboard, representing the Indigenous children who never returned home from residential schools, to contemplate overnight. (Katsitsionni Fox)

This is not only morally imperative; it's a critical step toward a livable future — and it's more possible than you might think.

As director of the Nuns & Nones Land Justice Project, I am heartened by the members of more than 100 religious communities who are exploring these possibilities as part of their land legacy.

The Doctrine of Discovery is deeply connected to climate devastation and racial injustice today. Historically, it compelled European nation states to "invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue" all non-Christians, and declared that any land not inhabited by Christians was available to be "discovered" and claimed outright.

Members of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Monroe, Michigan, and the Dominican Sisters in Adrian, Michigan, participate in a workshop offered by the Land Justice Project. Featured local speakers Madalene Big Bear of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, and Erin Preston Johson of the Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund. (Nuns & Nones Land Justice Project/Brittany Koteles)

It paved the way for the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the genocide of Indigenous peoples, and the colonization of 84% of the land on Earth by European nations. These impacts reverberate today. As Diné elder Pat McCabe said during the webinar April 5, the doctrine "wasn't just a moral or ethical imposition; it was the beginning of the destruction of this Mother Earth in its entirety."

The doctrine's logic of white Christian superiority — over all creation — was cemented into a modern economy that hinges on the extraction of people and the Earth, for the profit of a few. Ninety-eight percent of U.S. private land is owned by white people. That land has been stolen and passed down for generations, contributing to a Black-to-white wealth gap of 1:16. And it's being developed at a rate of 1,500 acres a day — destroying habitats and ecosystems, while lining the pockets of overwhelmingly white-owned corporations.

In a March 2022 webinar, Deseree Fontenot summed it up well: "What you do to the land, you do to the people; what you do to the people, you do to the land."

Sisters and associates from five religious communities in the Dubuque, Iowa, area attend a two-day workshop on land justice with members of the Land Justice Project. (Nuns & Nones Land Justice Project/Brittany Koteles)

Potawatomi scientist Robin Wall Kimmerer in her book Braiding Sweetgrass brings this to life in parallel stories: the displacement of her ancestors, and John Deere's invention of the steel plow: "It all got 'broke' at the same time — the prairie, the treaties and the relationship between people and land. Between 1800 and 1930, 95% of the world's Tallgrass prairie was converted to farmland. ... What took 12,000 years to become rich with thousands of species, took only 120 years to turn into an ecological desert, composed essentially of two species: corn and soybeans."

With the loss of deep-rooted prairie plants came a massive erosion of soil. Today, some scientists calculate that the Earth has 60 seasons of topsoil left.

But as the climate clock ticks away, we keep choosing our own demise. In the same month as the doctrine's repudiation, the Biden administration gave the green light for the Willow Project, an Arctic Circle drilling operation slated to extract 600 million barrels of oil over the next three decades. Willow goes against the urgent warnings of climate scientists, as well as Biden's own promise to halt new fossil fuel drilling operations.

Why? According to insiders, the Biden administration "made the internal calculation" not to fight the company because "refusing a permit could have triggered a costly lawsuit."

Even with a livable planet hanging in the balance, we remain beholden to a legal property construct built on Discovery-era fallacies and violence.

"If we believe that every single legal contractual agreement on the planet has to be fulfilled, we're going to lose this Earth," McCabe warned in the April 5 webinar.

If we want a liveable planet, we have to act outside of the options we've inherited. Through decisions about land, Catholics can help model a new way forward. Rather than relying on conventional real estate processes, religious landowners can prioritize the protection of land, the regeneration of its health and the restoration of access, governance, legal control and loving relationship of land to those most harmed by the doctrine.

There are religious communities who are daring to do things differently. Through the Land Justice Project, I have accompanied these communities and witnessed the diverse and varied nature of this work: It is rural and urban. It is pursued by communities with financial abundance, and communities who need outside funding support. It's often messy and confusing, since the path is less traveled — but it is also creative, sensible and rooted in relationships.

Shinnecock kelp farmers Donna Collins-Smith, right, and Danielle Hopson Begun check a line of sugar kelp being grown in Shinnecock Bay on eastern Long Island, New York. The lines are covered with rich, brown, translucent sugar kelp, which has a biting taste that is both salty and sweet. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

It looks like Troge reclaiming her ancestors' practice of growing kelp, which in turn restores the polluted waters of Long Island, New York. And it's the Sisters of St. Joseph of Brentwood, New York, offering their coastal property as a long-term home for the project.

It's Callie Walker, a Methodist pastor in Virginia, learning about Black land loss from Duron Chavis. Six months later, she donated her family farm to an "Agrarian Commons" led by Duron and other BIPOC farmers.

It's Black- and Indigenous-led land trusts like the Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust, the Niamuck Land Trust and others who are prioritizing ecological and cultural restoration, and the allies that are entrusting their lands to them.

It's Liseli Haines, a Quaker who returned 30 acres to a collective of Oneida women in 2019. That collective includes Michelle Schenandoah, founder of the nonprofit Rematriation, which connects Indigenous women to heal and reclaim their culture.

Advertisement

Three years after that Oneida land return, Michelle served as a spiritual adviser for the Assembly of First Nations delegation to the Vatican last year. In a private audience with Pope Francis, Michelle focused her statement squarely on the Doctrine of Discovery, explaining in the webinar that she called on Francis "to rescind it, to revoke it ... not just repudiate it. To pull it forever from the ability to ever be relied upon by any nation state ever again."

But the doctrine wasn't rescinded; it still undergirds the laws of the United States, of many other nations and of our own imaginations. Truly "rescinding" the doctrine requires us to make new choices. For those whom the doctrine privileged, we have to face the facts.

"A deed may be a flimsy piece of paper, but it is also one of the heaviest things we hold," said Janelle Orsi of the Sustainable Economies Law Center in a legal resource for land return.

Francis has said, "We are not in an era of change; we are in a change of era." We are capable of living into a post-Discovery era — a society not focused on profit and domination — and the decisions Catholics make about land and wealth can be an active part of building that future.