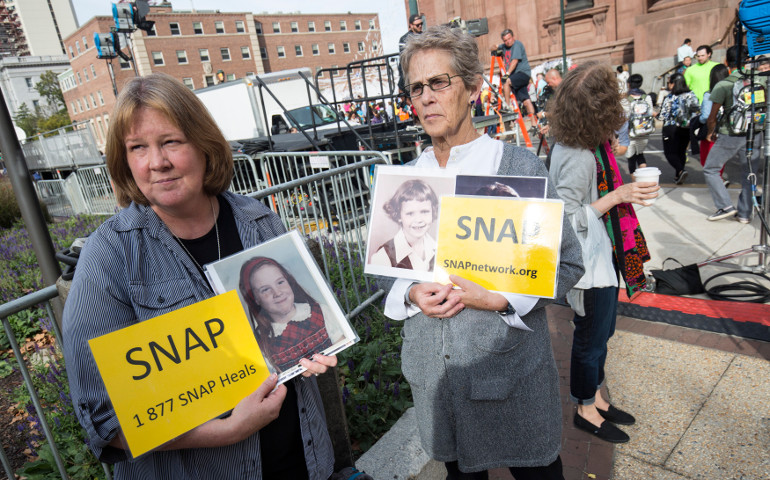

Becky Ianni of Burke, Va., and Barbara Dorris of St. Louis, both members of Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests demonstrate in front of the Cathedral Basilica of SS. Peter and Paul in Philadelphia Sept. 25, 2016. (CNS / Joshua Roberts)

In a matter of weeks, an extreme makeover changed the face of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP).

Gone is David Clohessy, its national director and the relentless force behind the group’s advocacy efforts.

Gone is Barbara Blaine, its president and the former Catholic Worker who founded the support network in 1988, in part through a phone call to the Phil Donahue Show.

What remains, SNAP says, is its wide network of volunteer leaders who perform “the vast majority” of its work outside public view, as well as its longstanding commitment to survivors of sexual abuse.

“I think our core mission has always been to help those who have been hurt and protect the vulnerable,” said Barbara Dorris, now SNAP managing director after 12 years as its outreach director. “We are still doing both and will continue to do both and maybe in kind of different ways.”

The change in personnel didn’t so much spark an examination of SNAP’s future so much as it fueled already ongoing conversations of what the highest-profile advocacy group against clerical sexual abuse of children, with 20,000-plus members, will look like in the future, who and how it will serve, and even what it might call itself.

“I think any organization has to change and grow to remain viable, to remain healthy,” Dorris said.

Along with SNAP’s changing of the guard has come adversity in the form of a lawsuit brought by former development director Gretchen Hammond, who has accused her former employer of accepting kickbacks from victims’ attorneys and abandoning its outreach to survivors. SNAP has denied the accusations and said it will fight the charges in court.

The timing of the lawsuit, filed Jan. 17, put a damper on the departures of Blaine and Clohessy, which board chair Mary Ellen Kruger and others insist were plans long in the making.

Clohessy, whose resignation became public Jan. 23, said he informed the board in mid-October of his decision to leave, and that took effect Dec. 31. Blaine, who resigned Feb. 3, told NCR that she had been giving the decision thought for months, confirmed by Dorris and Kruger as ongoing since at least October, when the main SNAP office moved from Chicago to St. Louis.

“I feel like I’ve done all I can in SNAP,” Blaine said.

Since her decision to step aside went public, she said the outreach from hundreds of friends, family and survivors has been “very overwhelming.”

“It’s really touching to hear from so many people and hear what encounters with me have meant to them,” she said.

Asked about SNAP’s biggest accomplishments in its 29 years under her guidance, Blaine described the impact of hearing just one survivor share his or her story as “a huge success,” a moment she estimated she experienced a few thousand times.

“Everyone is unique and inspiring and very special, so I appreciate all of those opportunities,” she said.

Another significant moment, Blaine said, came in 2011 when SNAP brought a case to the International Criminal Court at The Hague in the Netherlands against the Vatican, alleging the clergy abuse scandal amounted to crimes against humanity. Though the case was declined, Blaine said the resulting two U.N. committees, along with SNAP’s membership reaching 70-plus countries “speaks to the reality that this problem really is widespread.”

Blaine added that the church, though many issues remain unaddressed, has changed. “I think it’s much safer in the church today,” she said.

As for SNAP, Blaine believes it has made a difference and that with a strong network of leaders the organization has reached a point where it “can and needs to be bigger than the personalities or the personal agendas like myself or David or others had.”

“Wow,” Dorris said, “I don’t think I have those kinds of words of how to explain what [Blaine and Clohessy] have done and what they have created. I mean, they have just done amazing things.”

In the absence of Blaine and Clohessy, the five-member SNAP board intends to assume a more active role in daily operations. New additions may come to the now-three-member staff, but no decisions have been made about filling the vacated positions. Kruger hopes the new organizational model “alleviates a lot of the stress” on any one person and spreads it over a larger group. She added the board has many ideas and suggestions, but declined to provide further specifics.

One of the main areas where SNAP already sees a change is in its membership diversity. Beyond hearing from people abused as children in the Catholic church, it regularly encounters victims from other religions and institutions, such as schools, the Scouts and camps. It also hears more and more from adult victims of abuse and parents of survivors.

“We’ve gone from people abused by priests to this organization that’s talking to survivors in many, many areas. And we’re trying to help them and work with them and expose the same sort of problems in those institutions as were in the church,” Dorris said.

The larger scope has sparked conversations about whether the name SNAP still reflects what the network does today. No decision has been made, Dorris said, but the conversation remains ongoing, weighing its expanding purpose with the equity in name recognition.

“Right now, we’re going to leave it as SNAP,” she said.

The widening scope could place SNAP more within larger conversations about sexual assault, such as those taking place on college campuses. What SNAP can contribute, Dorris said, is changing society’s image of who is or can be a sexual predator.

“Years ago, the government created the ‘Stranger Danger’ program, and I think it’s something we’ve been fighting all along, that someone who molests or rapes a person is a dirty old man hiding in the bushes,” she said. “And what we bring to the conversation is, ‘No, predators can be charming, charismatic, well-educated respected members of the community.’ “

Other changes in the works fall more on operational lines, beginning with increasing SNAP’s number of support groups. Another is greater use of digital and social media to not only connect its current members but also to reach and inform a younger generation who might not recall the height of the clergy abuse scandal if not for the film “Spotlight.”

Complacency is a concern, Kruger said, meaning that in the absence of major new reports of abuse people may begin to believe the abuse issue is in the past. One counter exhibit: the recent investigation into sexual abuse within USA Gymnastics.

“Just because there aren’t stories on a very regular basis doesn’t mean that the issue still isn’t happening, that children aren’t still being abused,” she said.

On advocacy, the change so far has been in who’s doing the work, but events, leafleting and statements will continue. A rethinking of approach could come at some point, Kruger said.

But what is clear that won’t change is SNAP’s skepticism that the Catholic church will take steps SNAP views as necessary to address abuse and hold accountable those who allowed it. SNAP members will continue to judge Pope Francis and others by their actions, Dorris said, noting a promised accountability tribunal has yet to be formed.

Neither has Francis’ papacy yielded new fruits in relations between SNAP and the U.S. hierarchy.

“The response has been pretty much as it’s always been: to ignore us or to dismiss us,” Dorris said.

She added it would be “naive” to anticipate that a change in SNAP leadership will change bishops’ attitudes toward the advocacy group, but she said she remains “more than willing to listen” should any want to begin a conversation.

“If by some miracle it does, and they want to talk to us, we certainly would listen. But the safety of children and the survivors has to continue to be our first priority,” she said.

[Brian is an NCR staff writer. His email address is broewe@ncronline.org.]