(Unsplash/Haley Rivera)

For those who fear the Holy One,

God's mercy will not die,

Whose strong right arm puts down the proud

And lifts the lowly high.

God fills the hungry with good things,

And sends the rich away;

The promise made to Abraham

Is filled to endless day.

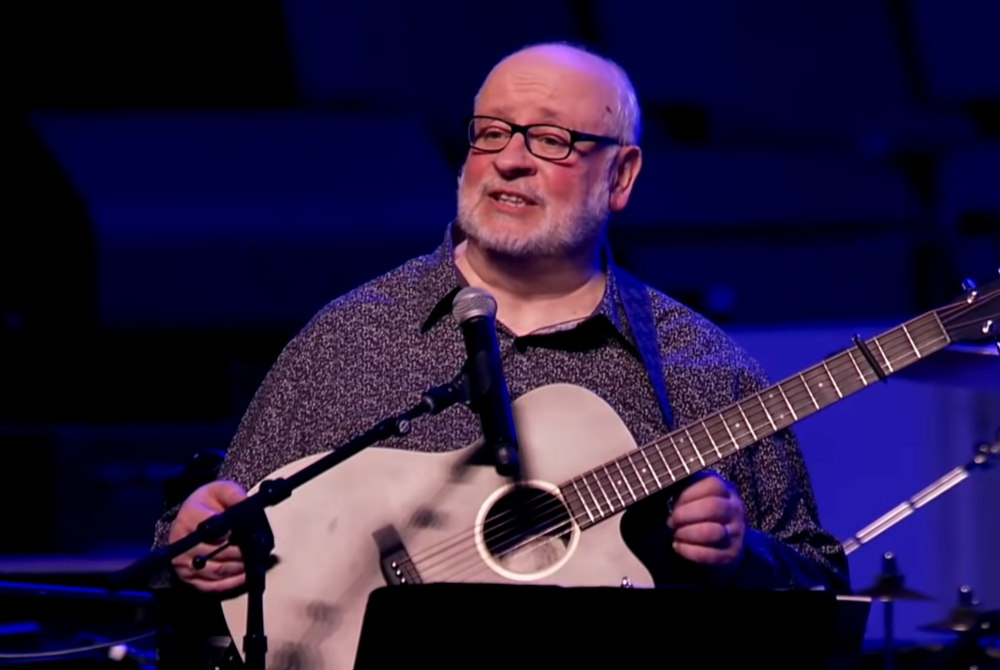

The Magnificat offers a two-part formula for creating equity: putting down the proud and raising the lowly. Big name church music composer David Haas is experiencing the first half of Mary's prayer. His publishers dropped him this year after allegations of decades of sexual abuse and spiritual manipulation of adult women came to light. Ten archdioceses, including Boston and St. Louis, have "asked churches not to play his music, pending the investigation," and others have banned him from performing, The New York Times reported.

Will we now also lift the lowly high, listening to the voices of those who traditionally haven't had the opportunity to speak? Or will we simply make lateral moves, replacing Haas' music with that of other white male composers?

Given that white men wrote the majority of the current English-speaking church repertoire, replacing Haas' songs with those written by women, gender noncomforming, Black, Indigenous or people of color will be challenging. It's not surprising that songs by white men were the majority of selections in the Mennonite Church's recent guide to replacing Haas' songs.

White male composers benefit from existing power structures. When sacred music publishers promote composers, rather than content, it consolidates power in a few celebrities. In a religious context, we often bestow such leaders with inordinate spiritual power. At the same time, the patriarchy of a church that won't ordain women, as well as the patriarchy of the society at large, keeps women in subordinate roles. Systemic racism and sexism have made success more elusive for talented nonwhite, non-male people.

Change comes one step at a time. Daily, we make decisions about whether to challenge or be complicit with inequitable systems. We need not have waited until this blaring wake-up call to raise up the musical compositions of the marginalized. The time I danced in worship to Haas' adaptation and arrangement of the traditional Scottish song, "Holy Is Your Name," the music director assigned it, and I deferred to his expertise.

Catholic composer David Haas speaks during a session of the Los Angeles Religious Education Congress on March 24, 2019. (Screenshot from YouTube/RECongress)

It is revealing that Haas chose to arrange a version of Luke 1:46-55 that neglects to flesh out the second half of the Magnificat's formula. Incredibly, it does not mention that God lifts up the weak and lowly — the line that many people associate with the Magnificat — only that God feeds the hungry. Haas revised the Scottish version's lyrics to make them gender inclusive, but did not correct the glaring oversight. By neutralizing the language but not providing a prayer of uplift for the oppressed, he made oppression even more palatable for those in power.

It did not occur to me to suggest that a female, gender nonconforming and/or BIPOC composer might be a more appropriate choice for Mary's prayer for social justice — that people on the margins can speak to oppression, that their interpretation of the prayer might be insightful and helpful, that they might actually mention lifting the lowly high, as Sr. Anne Carter of the Society of the Sacred Heart does in her version quoted above. I've learned my lesson and, in the future, will be more conscious of the genesis of the songs I embody in my ministry. I think we all will now.

Ideally, a church's transition to more representative music is part of a larger diversity and inclusion initiative. Often, unfortunately, our leadership does not reflect who is praying in the pews. We want how we worship to reflect who we are and who we aspire to be. An effort to diversify our music might begin with an inventory of currently used songs to see how the composers and lyricists reflect the demographic composition of the community.

Women make up at least half — and frequently more than half — of most congregations, so ideally at least half of all songs sung in worship would be composed by women. And there are plenty of fine options. Bernadette Farrell also composed a version of the Magnificat. Using the work of female and gender nonconforming composers goes hand in hand with advocating for their equal representation in the church.

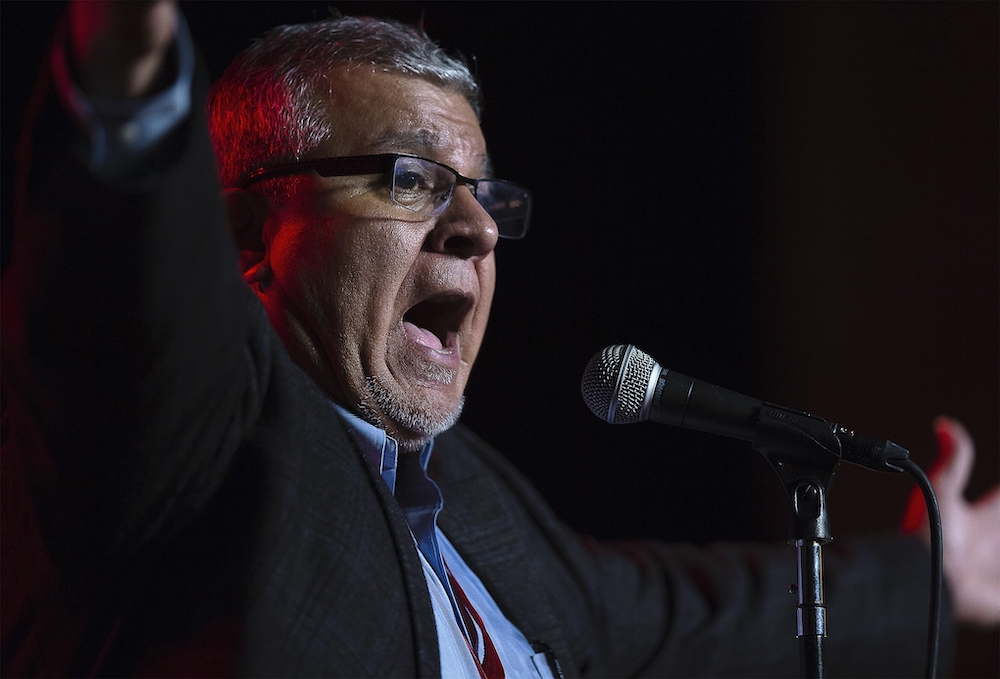

The representation of Black, Indigenous and people of color in church communities varies significantly from congregation to congregation. Therefore, each church has an opportunity to discern what music is representative of and speaks to its community. Choosing music from cultures not well represented in a congregation requires careful consideration to avoid cultural appropriation. The common African American expression, "They want our rhythm but not our blues," cautions that celebrating the joys of a culture without also living into its struggles can be duplicitous. African American composer Leon C. Roberts, Hispanic composer Pedro Rubalcava and Asian American composer Chris De Silva offer versions of the Magnificat.

Pedro Rubalcava, director of music development and outreach at Oregon Catholic Press in Portland, leads delegates in song Sept. 20, 2018, during the Fifth National Encuentro, or V Encuentro, in Grapevine, Texas. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

There are some, but not enough, resources for finding the work of women, gender nonconforming and BIPOC composers and learning about them, their circumstances, motivations and inspirations to provide informed interpretations of their work. Searching for and sorting through options takes diligence. The podcast, "Open Your Hymnal," will be highlighting a greater diversity of women and BIPOC composers in its upcoming season. GIA's Unbound project is creating a platform that raises new and diverse voices. Oregon Catholic Press also has a good track record of promoting diverse composers and music.

Searching for alternative composers is just the beginning: we also need to support them. As we scurry to find musical compositions to fulfill our diversity initiatives, we can also establish a pipeline for nonwhite, non-male composers. The Calvin Institute of Christian Worship has done amazing work engaging diverse voices. And the One Call Institute, a summer institute for young liturgical musicians, is committed to the work of representation in music programming.

The downfall of David Haas took over three decades. We have work to do to mend the harm and begin creating the diverse chorus of voices that can celebrate the fullness of our humanity. Let's allow Mary's call to social justice to guide us in lifting up nonwhite, non-male voices in our worship.

[Michele Beaulieux is an advocate against sexual violence, a liturgical dancer and an identical twin. She lives in Chicago and blogs about creating a culture of consent at www.reservoirofhope.blog.]

Advertisement