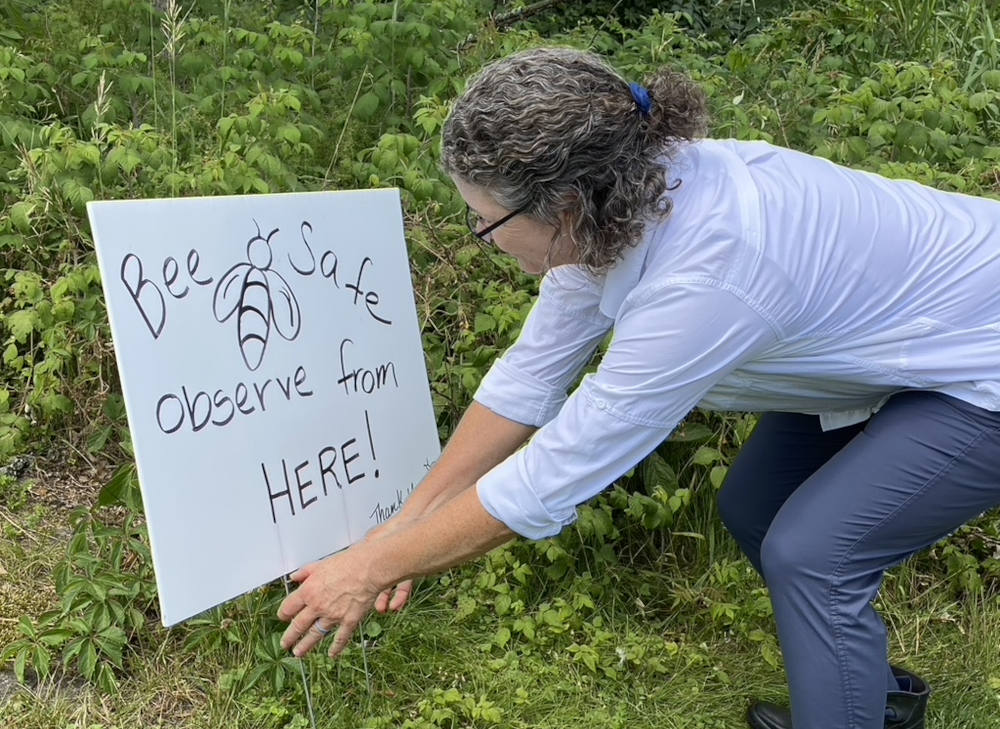

Cindy Thompson adjusts a sign at the Mercy Ecospirituality Center in Benson, Vermont. She and her husband, Chris Thompson, spent six weeks in a Sisters of Mercy program that focuses on reverence for the Earth, sustainability and acting in harmony with creation. During their stay, the retired couple helped transition two cyclone-shaped bee swarms to new hives. (Marybeth Redmond)

When a honeybee swarm appeared in the bee yard this summer at the Mercy Ecospirituality Center in Benson, Vermont, it presented three volunteers with an unexpected opportunity to participate in the birth of a new hive.

Bekah Kornblum, 29, of Dallas, and Cindy and Chris Thompson, a retired married couple from Atlanta, donned protective beekeeping gear to help catch the cyclone-shaped swarm and transition it to a fresh hive. The trio came to the 39-acre farm in the lush Green Mountains through a six-week service immersion program with Mercy Volunteer Corps.

Jars of honey filled at the Mercy Ecospirituality Center, in Benson, Vermont. (Kayla Buxton)

In their short time here, not one, but two swarming events occurred within a week of each other. Swarming activity, which typically occurs from May to July in the Northeast, is a sign of a healthy, reproducing colony. Worker bees, sensing cramped quarters in their existing hive, divide up the colony and half the high-pitched buzzers go off in search of new living quarters.

A local bee hobbyist coached the Mercy staff and volunteers through the careful "swarm catch" process, helping to relocate the displaced colonies to more spacious hives. Together, they later combined their hive frames filled with honeycomb from a previous harvest and extracted, filtered and bottled 56 pounds of raw golden honey.

For the Mercy volunteers — self-described city dwellers — witnessing thousands of honey bees congregating on a single bush looked like something out of a science fiction movie.

Kornblum, who came here to explore her "interconnectedness with Earth," teased that she was not so keen on "becoming one" with the bees quite like this.

Mercy Ecospirituality Center volunteers this summer helped re-hive two swarms of bees. They also worked with the staff to harvest honey. (Kayla Buxton)

A short-term immersion in nature

For the second summer in a row, the Vermont center and farm has served as a six-week immersion site for Mercy Volunteer Corps, or MVC, with a specific focus on reverence for the Earth, sustainability and acting in harmony with creation.

MVC, a partner ministry of the Sisters of Mercy based outside Philadelphia, traditionally offers yearlong placements at sites throughout the U.S. and Latin America. Nearly 1,200 lay alumni have completed the 12-month program, contributing more than 2 million service hours since 1978.

Over the years, MVC staff kept hearing the call for shorter placements that would provide greater accessibility for working adults. Pope Francis' 2015 encyclical, "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," espousing greater concern among Christians and all people toward conservation of the earth, was also a timely catalyst.

Mercy Sr. Anne Curtis, a former MVC board member and current executive director of Mercy Ecology Inc., based in New England, put two and two together and proposed Vermont as the pilot site for the first six-week program, which began in summer 2021. That volunteer cohort consisted of several 20-somethings; this summer, Kornblum and the Thompsons brought a multigenerational flair.

For the second summer, the Mercy Sisters' Vermont farm has served as a six-week immersion site for volunteers. From left, are Kayla Buxton, program coordinator; volunteers Cindy Thompson and Chris Thompson; Mercy Sr. Elizabeth Secord, director; Mercy Sr. Anne Curtis, executive director; and Bekah Kornblum, volunteer. (Marybeth Redmond)

Curtis notes that many Mercy volunteers, in particular younger ones, bring a deep hunger to their time at the Mercy Ecospirituality Center.

"They are seekers, spiritual seekers," she said. "Not just looking for an experience around the environment, but how to bring together their own internal connection to the mystery or divine with the care of all creation in the midst of what's unfolding on Earth."

The nonprofit organization hopes to design additional short-term service experiences around some of the religious congregation's "critical concerns," or identified priorities of immigration, racism, women, nonviolence and of course, the earth.

Volunteers bring vibrancy, knowledge

Summer swarms have become less common in Vermont in recent years. Pesticide exposure and a warming, drying climate have contributed to increasing bee colony collapse. As a result, the two swarming events at the Mercy farm this year were cause for great celebration.

Kayla Buxton, program coordinator for the Mercy Ecospirituality Center, said the timing was impeccable for providing an immersive beekeeping experience for the volunteers, in addition to their other responsibilities of caring for the gardens, sheep and chickens, providing hospitality to retreatants and participating in community life.

"The volunteers come with such a vibrancy and a diverse knowledge set," said Buxton, who returned home to the Green Mountain State after five years of city life in Boston, yearning for the calm, rural environment where she grew up. "They have a hunger to learn and are so excited and passionate about the things they don't know yet."

Mercy Sr. Elizabeth Secord, director of the Mercy Ecospirituality Center, believes the volunteers are a critical component to helping the Sisters of Mercy fulfill their mission.

"Our aim is to help people fall in love with the earth," she said. "And they [volunteers] help us to see with different eyes as they are exploring and becoming conscious."

Secord lives onsite at the center, with its nearly 40 acres of rolling meadows and woodlands that was gifted to the Vermont Sisters of Mercy by the Benedictine Monks of Elmira, New York. "The place feels holy," Secord says. "It's a long time that people have come here to pray and be present, and I think that has helped to create sacred space."

The Mercy Ecospirituality Center, which opened in 2010, is outfitted with solar panels for energy storage, an electric car charger, composting and recycling systems, and staff and volunteers actively work to restore the land by eliminating invasive species like wild parsnip.

The site also boasts a Cosmic Walk, a 0.2-mile trail that weaves through the woods marking the roughly 13.7-billion-year history story of the universe. Twenty-two significant "moments of grace" mark the pathway beginning with the original Big Bang; the last three feet of the trail represent human life on earth as we know it today.

The "walking meditation" seeks to evoke a sense of kinship with all beings, and the realization that an evolutionary universe is always unfolding.

City dwellers in rural Vermont

Bekah Kornblum, a product of 16 years of Catholic education with a degree from Creighton University, previously completed the traditional one-year MVC program in Sacramento, California, 2015 to 2016. When she learned about the multiweek Mercy stint in Vermont, one that she could wedge between a job change, she was all in.

Bekah Kornblum of Dallas calls working in the gardens a time of "adoration." (Marybeth Redmond)

She calls working in the gardens a time of "adoration" as she "watches the vegetables become a version of what I see in the store." Back home, she lives in a one-bedroom apartment in urban Dallas where she describes the air quality as poor; plus, there's no mandatory recycling across apartment buildings, a reality she finds frustrating.

It's quite a long way from the pristine mountain environment she found herself in this summer.

"The interconnectedness of everything is something I am exploring and want to find other avenues into," said Kornblum, whose service time has sparked a deeper interest in Celtic earth-based spirituality. "It's not just our relationship with animals, but it's the soil and the food and our neighbor; it's bigger than we imagine."

Despite her Jesuit formation in college, she gravitated toward the Mercy Sisters and MVC, both grounded in the charism of founder Catherine McAuley. Kornblum was attracted to a religious congregation with women at the forefront working to cultivate mercy and justice through compassionate service.

Kornblum's ultimate goal is not to abandon the urban landscape, but to return with new consciousness and commitment. She recently joined the city's Slow Food chapter, which values whole foods, clean production and fair pricing.

"I'm not going to pressure myself to produce my own food solo," she said. "My curiosity is, how can I be connected to and support the systems that already exist in Dallas by investing in local farmers?"

Cindy and Chris Thompson traveled from Atlanta to Vermont this summer to spend time living close to nature at the Mercy Ecospirituality Center in Benson, Vermont. (Marybeth Redmond)

Mercy volunteers, Cindy Thompson, 60, and husband Chris, 64, now retired and living in Atlanta, met years ago as college students in the outdoor program at Georgia Tech.

"The ecospirituality concept just captured us," Cindy Thompson said. "We feel closest to God when we are in nature; that's just our passion, what we do."

After a 30-year affiliation with Our Lady of the Assumption in Brookhaven, Georgia, where Chris Thompson served as deacon and the couple remain grateful for the "incredible community and faith foundation [we] gained," the COVID-19 pandemic and added time for reflection it brought motivated them to consider alternative ways to live out their faith journeys.

"We're like a lot of people, we love our Catholic faith," Cindy Thompson said, "but so much of the hierarchy and patriarchy is challenging. We are being called to be in closer proximity to the people we live and work with, just as Jesus did."

They have immersed themselves in diverse spaces, including a racial justice ministry at a local Black Catholic church, a centering prayer group on Zoom and assisting at the "foot clinic" at an Episcopal church without walls serving the homeless.

The six-week experience at Mercy Ecospirituality Center fit well into their latest focus on trying new things. One of their primary projects at the Vermont farm was building a "rabbit fence" around the circumference of the raised-bed gardens to keep out the snacking critters.

The couple, along with Kornblum, also hosted a communitywide Mercy Ecology "BioBlitz" — a gathering of local scientists, birders and naturalists to help catalog as many plant and animal species as possible in one day. Together, they identified more than 200 species on the farm property and uploaded the data into the iNaturalist app to build greater awareness of the biodiversity on the land.

For Chris Thompson, establishing relationships with neighbors and rural farmers and tapping into their perspectives was enriching.

"I came to understand how much work is required to grow things; nature is not super forgiving," he said, having also helped prep produce for market at a nearby organic farm. "These folks are choosing a lifestyle that's not a job to them. They have chosen to work on the earth and share what they harvest with everyone. It's a real gift."

Advertisement

Mercy Volunteer Corps' Keri Gardner, who oversees the developing short-term programs, was in Benson this summer to shadow the volunteers and staff, and helped plant milkweed to create a landing pad and food source for the migrating Monarch butterfly, who days after was declared "endangered."

The earth-focused Mercy program, she said, allows people to enter a peaceful space where they begin to sense the vital linkage between nature and their inner lives, especially in a time of societal disconnection.

"So many of us are immersed in a fast-paced, throwaway culture that degrades the earth," Gardner said. "Our spiritual selves are connected to the earth, and we lose the connection with our deepest selves when we don't take care of creation."

Well-versed in the writings of Thomas Berry, Hildegard of Bingen, Teilhard de Chardin, John Philip Newell, poet Mary Oliver and other mystical voices, Curtis describes the Mercy Ecospirituality Center as a tangible example of "living gently" in the world.

"Living gently is grounded in the belief that God inhabits all that God has created," Curtis explains. "My neighbor is all of life, not just other human beings. And this is one way it might look to live in harmony with creation."