Honeybees cool off outside their hive on a warm day. (Steven Salido Fisher)

Some beekeepers come from generations of beekeeping. I am not one of those beekeepers.

When I first chewed raw honeycomb from a hive, I lived in the Catholic Worker shelter in Houston. I was not there as the shelter gardener or a caseworker that summer, but a volunteer interpreter — translating for migrants who had crossed the border.

"Tell them this comes directly from the hive in the garden," the visiting beekeeper instructed me.

My parents never taught me the word for "hive" in Spanish. "It comes from the house of the bees," I said in clumsy Spanish, a chunk of honeycomb oozing on my palm.

Honeybees store pollen inside the hive's comb. (Steven Salido Fisher)

I took a bite, and the honey warmed my tongue. The bees scared me, but it was good to share in something that didn't come out of our soup kitchen — again and again, we'd eat frijoles and rice for dinner on paper plates.

I began to learn that way: licking my fingers with honey-hungry shelter residents and a generous beekeeper during a Houston summer. Next, I checked out and read books from the library, and then I couldn't stop. Other beekeepers became my mentors. I learned more and got stung more. Friends began receiving honey from me for their birthdays. I adopted my own beekeeping apprentices. Now years later, I unpack my sweat-stained beekeeping suit each spring, still not quite sure how to say "beehive" or "apiary" in Spanish.

When warm weather comes, I visit my two beehives in Chicago, nestled in a garden cultivated out of a wrecked housing development, now vacant yet bewildered by the yellow-time of goldenrod and the tumbleweed litter of McDonald's wrappers and cigarette butts. In the heat of the afternoon, I open up the hives and begin to inspect them. My eyes google every motion on the comb — particularly for a plump abdomen racing across the hexagonal chambers of wax swelled with larva and nectar. Where is the queen?

I mostly see attached to nearly every comb worker bees of dutiful nobility, whose work is equal, in my eyes, to any of the queen's sovereign tasks. Sister workers. Not royal, but still devoted. Nursing the barely speckle of an egg, guarding the hive and foraging for pollen. "Yes," I think to myself, "I could spend an hour here listening to their wings and studying the zigzags of waggle dances, traversing landscapes of vacant lots ablaze with flowers."

In each hive, I find the queen. Both colonies are dwindling and weak from the winter. As a beekeeper, I decide their likelihood of survival this summer will be greater if I combine the two colonies into one. It is a delicate process that if done wrong, could result in both colonies' demise.

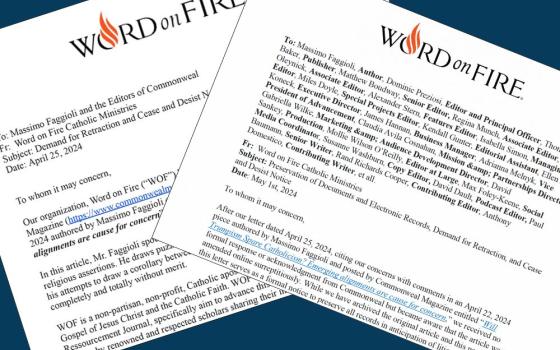

Combining two hives with a Catholic Worker newspaper between them permits an "introductory period" for their distinct odors to mix. (Photos by Steven Salido Fisher)

As distinct colonies, with different odors, they will kill each other if forced to share a hive without any introduction. So I unfold a newspaper on the box of the first hive before taking the stronger colony's box and stacking it on top. The only printed newspapers I still receive are from the Catholic Worker in Houston, and I save them precisely for this purpose. With a newspaper between them, the honeybees must tear and claw through headlines and articles, during which their odors will mix into one. The newspaper, then, is no barrier at all — but a threshold where they learn to belong to each other.

No house can have two masters. With the blade of my hive tool, I kill the extra queen by splitting her head from her abdomen. I am no St. Francis of Assisi. I do not tell the bees to praise and love their Creator. I give no sermon on pardon where there is injury, my hands raw and throbbing from sacrificial bee stings.

"Do what you must," I confide in them instead. If they do not, they will not survive.

Truly, did the wolf never bite St. Francis? And if not, wouldn't that deny his nature? Robbing the bees of their honey and crushing many of them during my inspections, I offer a gallon of sugar water as a consolation. A tamed nature is not what I ask of the honeybees to be in their company. Allowing them to be wild does not change the fact that I love them — on some days, even envy them. I watch a procession of honeybees return to the combined hive with an endless cargo of pollen. Some pollen is indigo or azalarin or apricot-orange, but most is ochre. I too want to chase flowers as a means of survival.

Advertisement

Some days, it seems like the whole world is flooded with fluorescent light and concrete, and I want their hive to be my ark, a desire that acknowledges both oblivion and salvation at once. The hive is an escape from floods of filth and garbage, our planet drowned in greenhouse gas emissions and toxic plastics. My worries swim in news reports of natural disasters and human-caused catastrophes. The beehive is a lifeboat — my faith held together by nails and carpenter's glue — with thousands of buzzing lives aboard.

I don't know if this essay will be an invocation of survival or an elegy for a wreck by the time it is published. After combining the two hives into one, I risk more stings from my sister workers and unzip my suit's veil. With sweat-washed hair and sun-drenched cheeks, I make inspection notes for my next return to the hive, trusting the newspaper will be torn and the two colonies harmonized. Still, I don't know yet if the honeybees here will survive the summer at all.

But I have learned that a single honeybee yields only one tablespoon of honey in its lifetime. Like them, I am going to concentrate on putting something sweet into the world, not as an act of denial nor as an act of hope, but as an act of nature that is worth the labor of a lifetime. Perhaps this hive will die or perhaps it will thrive. Either way, I will eat of and share its honey to the last sweet bite.