A seagull flies in front of a mural which shows a group of men, led by then-Fr. Edward Daly, right, carrying the body of shooting victim Jackie Duddy during 1972's Bloody Sunday in Derry, Northern Ireland. (CNS/Reuters/Cathal McNaughton)

As Northern Ireland prepares to commemorate the 50th anniversary of one of the worst massacres in its history, surviving family members are waiting to hear if a suspected perpetrator can be prosecuted.

"It still hurts as much today," said Kay Duddy, whose teenage brother Jackie was the first fatality in the Jan. 30, 1972, Bloody Sunday massacre, when British paratroopers fired on a protest against imprisonment without trial.

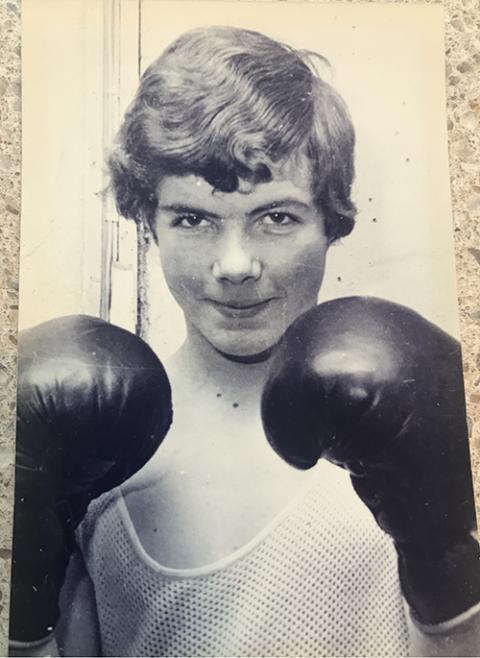

Duddy, 75, shed tears during an NCR interview at her home as she remembered how the amateur boxer, 17-year-old Jackie, cheerfully went out in his Sunday best to join the march and didn't return.

Kay Duddy, whose brother Jackie was killed in the Jan. 30, 1972, Bloody Sunday massacre (NCR photo/Claude Colart)

The fact that their loved ones were "demonized" by the military who labeled them "nail bombers, gunmen, petrol bombers" spurred her and other family members to campaign for decades until their names were cleared.

After two public inquiries, one soldier was charged. Last July, the prosecution of the paratrooper, named for anonymity as "Soldier F," was stopped over questions about the admissibility of available evidence.

Duddy joined some families in a legal challenge to this decision. Hearing the case in the Belfast High Court, Northern Ireland's first female chief justice, Dame Soibhan Keegan, announced on Sept. 23 she would give her decision at a later date. There has not been an update since.

John Kelly, 72, who was "totally devastated" when the prosecution of Soldier F was stopped, was himself on the march and lost a younger brother, Michael.

"I want to see them all punished, every one of them," he told NCR. "They murdered innocent people."

Jackie Duddy's final moments on Jan. 30, 1972, are immortalized in grainy news footage and photographs of him being carried under escort by Fr. Edward Daly, 39, waving a white handkerchief stained with the teenager's blood.

Also painted on a mural by local artists near where many of the victims were shot, the image has come to symbolize one of the darkest days in Northern Ireland's Troubles, and the year in which at least 500 people died.

Image of Jackie Duddy, who was an amateur boxer and was killed in the Jan. 30, 1972, Bloody Sunday massacre (Photo courtesy of Kay Duddy)

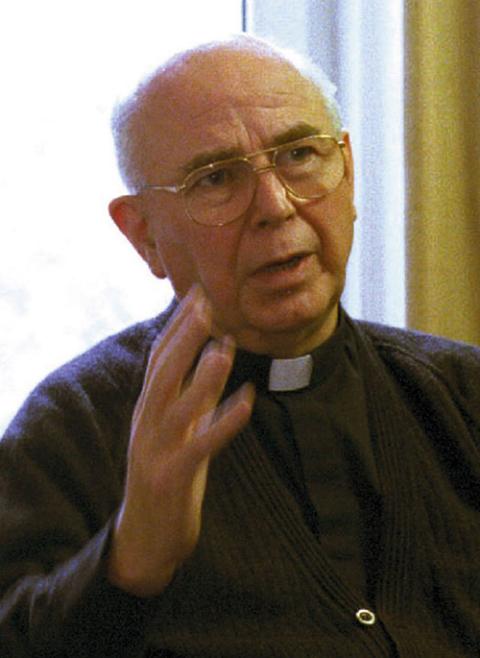

Daly, bishop of Derry from 1974 to 1993, later told Kay Duddy that, as they ran from the bullets, Jackie passed him, looked over his shoulder and smiled. "A shot rang out and [Daly] heard Jackie gasp and fall to the ground," she told NCR. "He used his hanky to try and stem the blood and managed to give him the last rites."

Just days before the Bloody Sunday anniversary, doctoral researcher Julieann Campbell, a niece Jackie would never meet, published an oral history: On Bloody Sunday.

Several commemoration events have been planned for Derry including a memorial service, a Families' Walk of Remembrance and the premiere of the play "The White Handkerchief."

What began as a spirited protest of some 15,000 people carrying banners and singing "We Shall Overcome," ended with 14 deaths, 13 on the day and another months later, and at least 14 injuries.

The protesters were forced to change their route when soldiers barricaded roads. After some stone-throwing, paratroopers fired a water cannon, tear gas, rubber bullets and, finally, at least 108 rounds of live ammunition.

Rejecting a quickly appointed British government inquiry, which exonerated the troops, the victims' families campaigned for decades for a new investigation.

Finally, the Saville Inquiry from 1998 to 2010 concluded that the victims had been killed unlawfully and then-British Prime Minister David Cameron apologized for the killings.

A crowd in Derry, Northern Ireland, celebrates June 15, 2010, after the release of the Saville report on the 1972 Bloody Sunday shootings. Then-Prime Minister David Cameron of Britain apologized for the killing by British troops of 14 Catholic demonstrators in Northern Ireland in 1972. (CNS/Reuters)

Amongst Jackie's clothes returned to his family in 1972 was a handkerchief embroidered with the name "Fr. E Daly." Kay Duddy later learned from Daly that Daly's mother, Susan, had sewed his name on his laundry items when he was away studying for the priesthood.

The Duddy family donated the handkerchief to the Museum of Free Derry, where it is displayed alongside Daly's stole and a framed photograph of Jackie, which his father William gave him when he became bishop.

The stole was presented by Daly's nephew, Ger Daly, in 2019. He told NCR it represents an aspect of Bloody Sunday not often highlighted — that his uncle, and the six other priests present on the day, were able give the last rites to those who were killed.

"He was there as a religious spiritual guide to comfort Jackie back to where he came from before he was born, to guide his soul to God," said Ger Daly.

Advertisement

Daly's last surviving sibling, retired solicitor Anne Gibson, 74, said she was "filled with great fear" when she received word of the massacre in a telephone call from the parochial house in Derry. In a telephone interview from her home in Belfast, she recalled gathering around the television to watch her traumatized brother criticizing the British Army's actions in an interview on the day of the shooting.

"We knew this was part of his priesthood and his shepherding of his flock and all we could do at the time was pray for him," she said.

Retired Bishop Edward Daly of Derry, Northern Ireland, in a 1997 file photo (CNS/Carlos Lopez)

She remembered how Daly later visited the U.S., "to speak his truth against the stories that were being told by political parties at the time of what happened in Derry that day."

"He had a passionate desire for peace, it colored his whole bishopric," she said. "He could never tolerate violence from any side and the desire that the truth of that day be told was his goal."

After he retired, Daly served as chaplain to a hospice center. It became "his whole life," she said of her brother, who died in 2016.

Remarking on Daly's strong working relationship with Anglican Bishop James Mehaffey, Bishop Donal McKeown, Daly's second successor in Derry, told NCR how churches in Derry have long worked together and how they still seek a joint response to community issues.

McKeown is part of an interchurch group under the umbrella of the Irish Council of Churches "looking at what specific approach we can bring to the whole question of processing the pain of the past," he said.

"For most people who died during the Troubles, simply getting the truth of what happened will be the best they can expect," McKeown said.

Kelly told how his brother Michael had a viral infection at age 3 and a doctor suggested he would not survive. When a priest asked his mother Kathleen "to give him up to God" she refused.

John Kelly, whose brother Michael was killed in the Jan. 30, 1972, Bloody Sunday massacre (NCR photo/Claude Colart)

Michael recovered and grew into a teenager who loved music, particularly that of glam rock singer Marc Bolan; studied; worked as an apprentice sewing machine mechanic; kept pigeons, and had a steady girlfriend.

Hundreds congregate in Derry, Northern Ireland, during a Jan. 30, 2002, service marking the 30th year since Bloody Sunday. (CNS/Reuters)

His mother initially refused his request to go on the march but relented. Even then she followed him, and after losing sight of him, went to her sister Martha's apartment for a better view.

"She did apparently see him at one point, and she called out to him but he didn't hear her," Kelly said.

While his father John died in 1991, Kathleen lived to see the Saville Inquiry start but died six years before the result.

"She would always ask me what was happening in the inquiry. And we knew that she was coming to the end of her time," he said. "Eventually I told her that Michael and all the rest were declared innocent. I told her a lie, but it ended up the truth."

On a recent tour of the streets where the shooting happened, Paul Doherty indicated the spot on Rossville Street where Michael Kelly was shot dead on that "very cold, crisp winter's afternoon."

He is not just a tour guide showing visitors the route the marchers followed. Bloody Sunday is personal to him. His own father, Patrick Doherty, 31, was shot dead as he tried to crawl to safety near where Michael fell. Paul was 8 years old.

A man who ran to help Doherty, Bernard McGuigan, 41, was shot in the head.

All along the way from the Guildhall to the famous Free Derry Corner, Paul Doherty greeted passersby, each one either family of a victim of Bloody Sunday or someone who was there.

Paul Doherty's father Patrick was killed in the Jan. 30, 1972, Bloody Sunday massacre. Here, Paul stands in front of one of the buildings hit by the soldiers' bullets, which is now adorned with an artistic visualization of the sound of the civil rights anthem "We Shall Overcome." (NCR photo/Claude Colart)

"I get great satisfaction from telling people from around the world what really happened on Bloody Sunday," Doherty told NCR.

Then Doherty stopped outside the front of the Museum of Free Derry, opened in 2017 by the Rev. Jesse Jackson.

Near two large holes from bullets that thudded into the side of the building is a thick rusted steel wall. Into the wall local artist Locky Morris has etched a visualization of the sound of the civil rights anthem "We Shall Overcome."