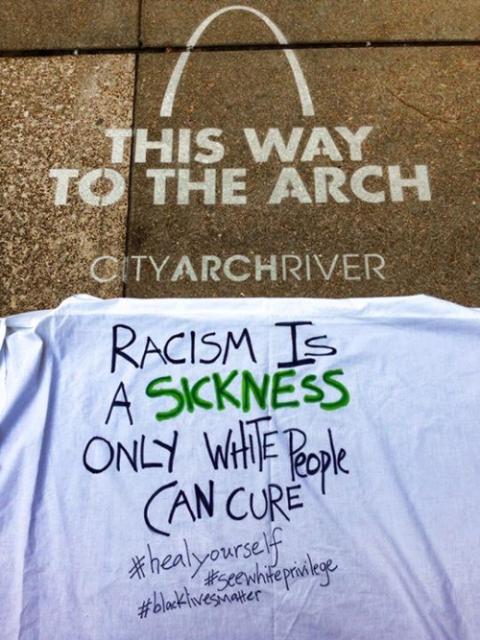

Participants at a 2017 Black Lives Matter demonstration in St. Louis. (Kristen Trudo)

Is the Catholic Worker movement a "racist institution"?

Members of the movement have been grappling with that question with particular intensity since participants in a fall 2017 Midwest Catholic Worker Faith and Resistance Retreat sent out "Lament. Repent. Repair. An Open Letter on Racism to the Catholic Worker Movement."

Debates about the letter's language and the Catholic Worker's history have sometimes been heated. But they have also brought increased attention to the need to combat racism both in the movement and in society, as well as highlighted ways in which communities are already making progress.

The Catholic Worker movement, a decentralized network of around 250 small communities founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin in 1933, is perhaps best known for its houses of hospitality and its pacifist stance.

The movement also supported racial justice from the beginning. At the suggestion of black Catholic Worker Arthur Falls, the masthead of its flagship newspaper features a black worker and a white worker clasping hands; the Catholic Worker newspaper has often discussed issues of racial justice; and, since the early days, members have participated in various projects to reach out to or further the rights of people of color.

Recently though, some Catholic Workers have been asking if the movement, which remains largely dominated by white people, has done enough to address racism.

Inspired by several recent faith and resistance retreats focused on racism and white supremacy, many Midwest Catholic Worker communities have increased their interest in racial justice work, particularly examining how racism might play out in their own communities.

At Karen House Catholic Worker in St. Louis, the community — galvanized by protests in nearby Ferguson, Missouri — increased its anti-racism activism and examined how "white supremacy culture" had become embedded in the house, said community member Jenny Truax.

"A lot of us feel if we are just generally open and welcoming, then every single identity should feel welcome. That's not necessarily the case," said Truax.

The movement needs to ask why it mainly attracts middle-class white people and "acknowledge that structurally there are probably things in our culture and the way we do things that unintentionally exclude other identities," she said.

In the Rye House Catholic Worker community in Minneapolis, members have become more involved in movements led by people of color, especially opposing police violence, community member Joe Kruse said, and become more aware of how white privilege affects their work.

These experiences led a group of mostly younger Catholic Workers to write the "Lament. Repent. Repair." letter. Reprinted in the first edition of the Catholic Worker Anti-Racism Review in spring 2018, the letter asserted that the Catholic Worker is a "racist institution" that has often unintentionally excluded people of color, failed to confront structural racism, and ignored and perpetuated white privilege.

A banner at the Ferguson October Weekend of Resistance, a national mobilization in St. Louis in 2014. (Sarah Griesbach)

As remedies, the letter suggested increased reflection and discussion about racism, following the lead of people of color, examining neighborhood dynamics and using white groups' often greater access to resources to support people of color.

Brian Terrell, of Strangers and Guests Catholic Worker Farm in Maloy, Iowa, was supportive of some of the suggestions but objected to the letter's characterization of the Catholic Worker as a "racist institution."

"I think it debases the language to use the same words to describe the Ku Klux Klan and the Catholic Worker," Terrell said. "They say despite best intentions the Catholic Worker is a racist institution, but racist institutions don't have good intentions. … We are all infected with racism, but a truly racist person thinks that's normal."

In a debate that largely seemed to fall along generational lines, other Catholic Workers, especially some, like Terrell, who have been part of the movement for decades, joined in his criticism. They objected that the Catholic Worker is not an "institution" at all and pointed out examples of past anti-racism work.

Megan Macaraeg, a member of Karen House Catholic Worker who was born in the Philippines, felt compelled to respond to an email from Catholic Worker Ciaron O'Reilly that referred to the letter writers as Midwest "identity politics kids," accused them of arrogance and lack of depth, and suggested they should leave the movement.

"My identity matters a lot. My people and our history of fighting above and underground, genocide and imperialism, matters," she wrote. "I don't read the Statement as a facile, identity-based indictment of our movement. The critiques are based in structure and an analysis of the real material conditions we are confronted with. … Where is the harm in looking at that, mulling it over, talking about what is to be done?"

Terrell isn't opposed to discussing racism but objected to the letter's implication that the work hadn't begun until recent years.

"The good advice that the letter had about things that people ought to start doing is all stuff that we have a history of. … We can start new saying nothing good has happened yet or we can say, 'Wow, we have a real heritage and we have a lot to live up to and a lot more to do,' " Terrell said.

Advertisement

Those who have been involved with writing or promoting discussion of the letter do recognize positive parts of the Catholic Worker's legacy, but they also insist they have something new to contribute to the conversation.

"It's right to point out that the Catholic Worker has fought against racism since its early days; that has been a part of its ethos," said Kruse. "I think that one nuance that this new conversation has offered the movement is about how white supremacy is embedded in our community structures. … It's given us a little more intimate of a look into where racism could reside."

Macaraeg told NCR she felt comfortable joining Karen House as a person of color because of the work they had already begun to do on racism, helping to "make the place they call home a place that people of color want to be at and lead from within."

Macaraeg also said she brings a different perspective to the movement "as a worker and a woman of color and a single mom who has sort of gone through some of the things that the women in our house are currently going through."

While Macaraeg thinks it would be valuable to have more people of color in the movement, she pointed out that Catholic Workers might not be able to immediately jump into recruiting them. "Actually having personal and professional relationships with people of color as a white person is the first thing," she said. "You can't even ask people [to join] if they're not in your life."

Truax and Kruse also mentioned as contributions the recent discussion has made to Catholic Workers' thinking about racism: a focus on issues with policing and criminal justice; a commitment to following the lead of people of color and being accountable to them; and an examination of how privilege affects the movement.

Although these ideas aren't totally new — for example, Day's last arrest was with striking farmworkers in a movement led by Latinos such as Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, and Terrell gave examples of Catholic Workers protesting prisons and combating police brutality — having such an explicit focus on those ways of combating racism is a more recent development, Truax and Kruse suggested.

Activists hang a banner that used ashes obtained from burning papal bulls that justified slavery and manifest destiny on the Cathedral of St. Paul in St. Paul, Minnesota, on Ash Wednesday, March 1, 2017. (Center for Prophetic Imagination/Zed Edgeton)

While disagreeing in some areas, Catholic Workers do agree it is important to continue the conversation.

"The folks who went to [the faith and resistance retreats] clearly had a very profound experience and I don't want to dismiss that at all or question that. It's very valuable and we need to hear it, but they're gonna need to listen to other people too," Terrell said.

He was happy to see some indications that younger Catholic Workers recognize they don't have all the answers, are open to others' wisdom and understand that everyone cares about addressing racism.

"I don't know anybody who doesn't think we should have a discussion on racism," Terrell said. "I don't know anybody who thinks the Catholic Worker has been free of racism."

Given this agreement, Catholic Workers are hopeful that they can move past some of the debates and do the anti-racism work they all believe should happen.

"I am super interested in, not debating whether philosophically the Catholic Worker is racist, but doing work with the understanding that it is to dismantle [racism], to make our communities more inclusive and better allies to communities of color," said Truax. "I'm really excited to see where the conversation is going."

[Maria Benevento is an NCR Bertelsen intern. Her email address is mbenevento@ncronline.org.]