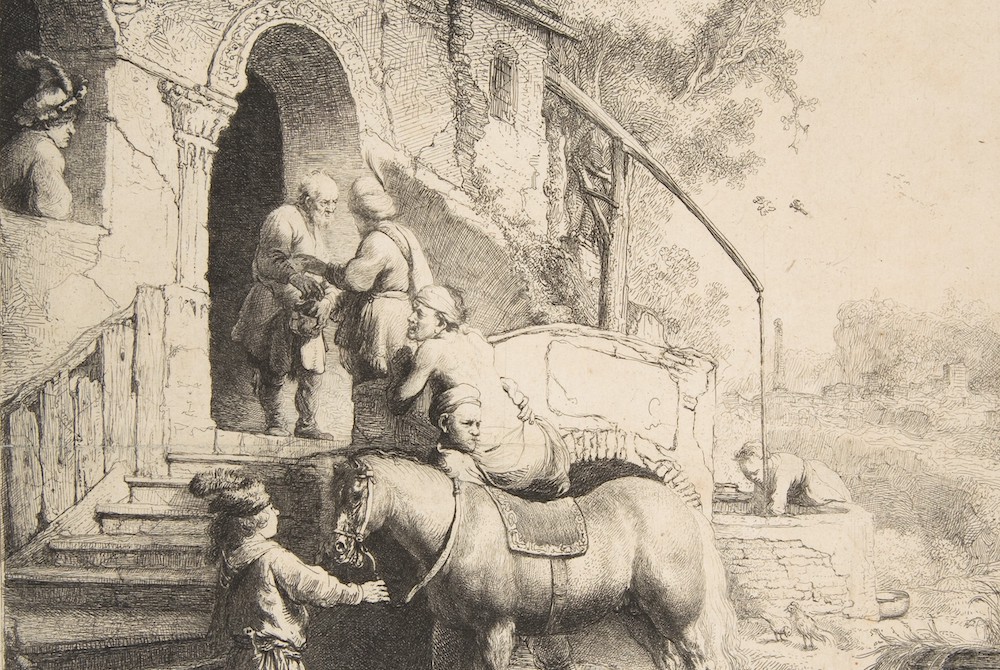

Detail of "The Good Samaritan," etching by Rembrandt van Rijn, 1633 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Rembrandt's intriguing and enigmatic etching, made in 1633, portrays the good Samaritan bringing the wounded man to the inn, an image that reverberates with implications for facing life in difficult times.

The inn to which the Samaritan brings the wounded man is in a state of disrepair. Deep cracks appear in the outside wall, some of the boards on the railing of the steps are broken, and the wooden eaves are in the same shabby state. It is in this decaying and sometimes disturbing world — considering the gratuitous act of violence the wounded man had just suffered — that the Samaritan's surprising act of mercy takes place, a place where everyday life continues as normal: A man gazes nonchalantly from a window of the inn as the wounded man is being helped down from the animal. A woman gets water from a nearby well. Birds are in the tree above her, leaves drift down to earth, two chickens stand just in front of the well, and the woman pays no attention to the Samaritan's act of kindness and mercy taking place just in front of her. And, in the right front foreground, a central location nearest the viewer, a dog, with its back to us, defecates on the ground.

The centrality of the dog is striking, and the structure of the painting leads viewers from the bottom right — where the dog performs a rudimentary bodily function common to all animals — along a diagonal to the left and back — where the Samaritan performs a selfless act of mercy.

Why do we only see the back of the good Samaritan at a distance but see the back of the defecating dog so prominently? The provocative image of the defecating dog seems designed, at least in part, to shock a polite audience, just as Jesus's use of a compassionate and merciful enemy, a Samaritan, would have shocked his initial audiences. In a previous study of this image, I concluded that the "dog most likely functions primarily as a playful aspect of verisimilitude, yet it illustrates that life inherently includes the sublime and the everyday, the unusual and the banal, the sacred and the profane, with the latter — in each of these polarities — often more prevalent than the former."

"The Good Samaritan," etching by Rembrandt van Rijn, 1633 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Such a perspective can serve as a description of the human condition itself, but when I revisited this image recently, I noticed that interpretations of Rembrandt's etching also shed light on divergent yet interlocking ways in which human beings respond to difficult circumstances.

One response is founded on hope: The parable of the good Samaritan challenges its hearers to reimagine themselves, the world, other human beings and God in radically different ways, and to put that new perspective into concrete action in their daily lives. Yet for centuries, instead of just relating a moral lesson, the parable became for most interpreters an allegory of Christian views of salvation in which the man (who symbolizes Adam) is attacked by hostile forces in the world (the thieves, who represent Satan) and is saved by Jesus (the true good Samaritan) who restores sinful humanity (the wounded man) to a right relationship with God in the church (represented by the inn). In these interpretations, the parable by Jesus has evolved into a parable about Jesus.

Some interpreters, then, envision such allegorical elements even in Rembrandt's down-to-earth representation, viewing, for example, the open door of the inn as symbolizing the door of heaven, a passageway to eternal salvation that opens for those who perform such acts of mercy. This interpretation reflects the hope that such acts of mercy will be rewarded, as they are in Jesus' parable of the sheep and goats.

The second type of response, however, reflects an overall attitude of despair. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, for example, believed that the man in the window of Rembrandt's etching is the malicious leader of the band of robbers who earlier attacked the man, and the etching portrays the moment when the poor man is seized by the fear that he will soon be once again weak and helpless before the thieves who previously robbed and beat him. The notorious reputation of such inns and innkeepers in the first century can provide a rationale for Goethe's belief that the man at the window was one of the man's previous tormentors. Indeed, the parable itself reflects that some hearers may view the Samaritan's actions as foolhardy and naïve (e.g., entrusting the wellbeing of the wounded man to an untrustworthy innkeeper).

Advertisement

Another way to approach this image and the parable itself, however, is that this act of compassion and mercy takes place not just in the midst of evil or even in spite of evil, but as a radical and in some ways redemptive act against evil.

To be clear, the parable does not focus on what should happen to the perpetrators of such injustices, whether individual or structural; instead, it illustrates how one should treat the victims of injustices, no matter who they are.

The great theologian Howard Thurman believed that the parable of the good Samaritan demonstrated that the transformation of society ultimately depends on the transformation of individual human beings and that this personal transformation should create not just transformed individuals but a community of like-minded human beings (e.g., a "beloved community") dedicated to social transformation in response to the human need that surrounds them.

In times of personal and societal distress, it is often difficult to believe, as did Theodore Parker (and Martin Luther King Jr.) that the arc of the moral universe, albeit long, "bends toward justice." Thurman realized that the pervasiveness of injustice does not provide an "escape hatch" of despair that one's actions will not make a difference in creating a better society. He believed that there is a persistent struggle between good and evil, both in oneself and in society, and that all are responsible for acts of justice, mercy and compassion in the world of parable and in the world in which we live.

The command at the end of the parable, to go and do likewise, to show compassion and mercy to those who suffer injustices, focuses our attention on the need to transform ourselves into people who work actively on the behalf of other human beings who suffer similar injustices, doing our part to try to bend the arc of the moral universe toward justice.

The parable of the good Samaritan and Rembrandt's response to it accurately portray the injustices in their worlds and ours. They also do not downplay the fact that the results of one's actions to assist other human beings may be seen as foolhardy or even fruitless. Yet we will never know, unless, as Jesus urged at the end of the parable, and as Thurman himself suggested, that we "try it and see."