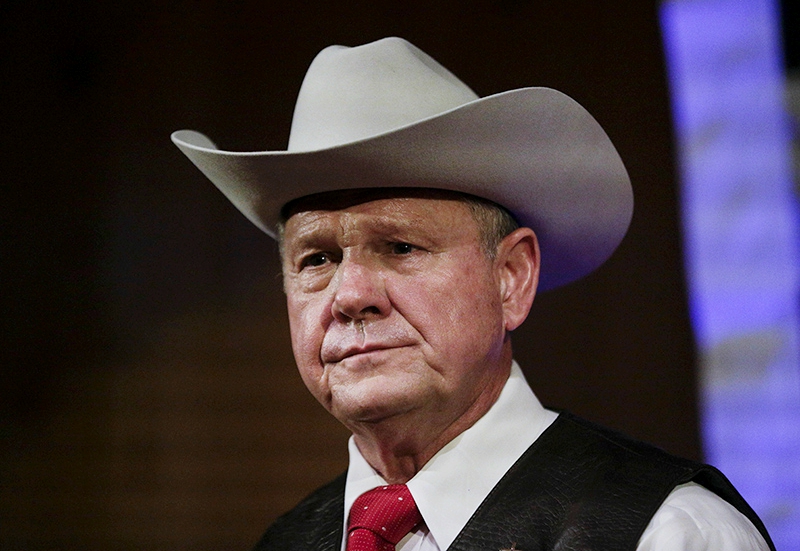

Roy Moore speaks at a rally in Fairhope, Alabama, Sept. 25, 2017. (RNS/AP Photo/Brynn Anderson, File)

Just as there are Catholics and then there are Catholics, so it is with Protestants.

Almost a year into the Trump presidency — especially after last month's startling defeat of one Protestant, Roy Moore, by another, Doug Jones, for one of Alabama's U.S. Senate seats — it's a good time to try to sort out how Protestants who voted for Moore and Donald Trump may differ from, well, lots of the rest of us Protestants.

Analysts say about 80 percent of voters who identify as white Christian evangelicals and participated in Alabama's special election voted for Moore. That's roughly the same percentage of white evangelicals who supported Trump in 2016.

When people describe themselves as white evangelicals (whether Protestant or Catholic) it can mean any of several things because, of course, not all evangelicals are alike.

But it's fair to say that they tend to read the Bible more literally than others; they emphasize personal salvation over concern about the covenant community; they generally believe in a literal fiery hell; they tend to line up on what society has labeled the "conservative" side of hot-button social issues. Which is to say that many of them oppose abortion under almost any circumstance; they generally (at least historically) have been against same-sex marriage; they often distrust the idea that climate change is affected by human activity; they're attracted to Christian nationalism; they mostly vote Republican and think Sarah Palin is much smarter than Elizabeth Warren.

By contrast, Protestants who avoid the "evangelical" label often do so with regret, recognizing that the word reflects the essential Christian obligation to share the Gospel with others. But to many people, the term has come to mean right-wing political choices and theological judgmentalism. And we non-evangelical Protestants would rather not be identified with the Jerry Falwells and Pat Robertsons.

What baffled non-evangelicals in the 2016 election and the recent Alabama election was how evangelicals could support people whose values and actions made a mockery of evangelical ideals. Trump: a self-confessed sexual predator, a man of multiple marriages and mistresses, a businessman deeply engaged in casinos, a man of xenophobic tendencies. Moore: a credibly accused molester of teenage girls, a man known to express racist views, a flouter of the law who had to be removed as chief justice of Alabama's Supreme Court.

How to explain all that?

Advertisement

The only explanation that makes sense to me is that evangelicals became one-issue (anti-abortion) voters who had so lost touch with what is true that they preferred to believe Moore and Trump when it came to he-said, she-said cases, which for both men really were matters of he-said, she-said, she-said, she-said, she-said, she-said, she-said, she-said, she-said, and on and on.

The Christian idea that we should know the truth and the truth will set us free seems to have been widely abandoned by evangelicals. And their unflinching commitment to opposing abortion under any circumstances means that they've made an idol of the issue, losing any semblance of balance. Idolatry will do that to you.

The more important test for Christians is not whether we're against abortion but whether we love God and love neighbor, as Christ commanded. It should be whether we weep with those who weep and mourn with those who mourn. It should be whether we work to free the oppressed and liberate the slaves. It's not about whether we condemn football players who kneel for the national anthem. It's not about whether we put anti-Darwin bumper stickers on our cars.

I'm not suggesting that there's no diversity of opinion and even diversity of theology within Protestant evangelical or non-evangelical congregations. There certainly is. But though our Protestant denominations have governance structures to guide us, we have no Vatican or Curia to rein us in. We are, thus, susceptible to hourly fashion changes.

In the end, we evangelical and non-evangelical Protestants are followers of Jesus separated by a common religion.

[Bill Tammeus, a Presbyterian elder and award-winning former Faith columnist for The Kansas City Star, writes the daily "Faith Matters" blog for the Star's website and a column for The Presbyterian Outlook. His latest book is The Value of Doubt: Why Unanswered Questions, Not Unquestioned Answers, Build Faith. E-mail him at wtammeus@gmail.com.]