James Cone in an undated photo (Mev Puleo)

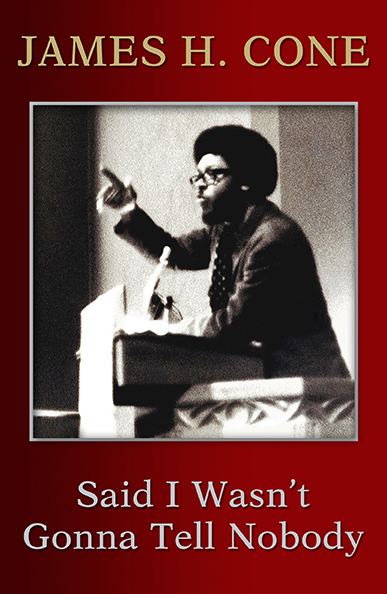

It's hard to read the Rev. James Cone's final book without thinking: This is a man who knew he was dying.

Said I Wasn't Gonna Tell Nobody is not a sentimental text, which makes the few instances of vulnerability all the more haunting. Phrases like, "As I come to the end of my theological journey ..." are offered casually and only in the service of larger themes, but — in light of Cone's death in April — they seem to jump off the page. That could be, however, because Cone doesn't give readers much else when it comes to his thoughts on death. Or on life, to be frank.

Though billed as a memoir, Said I Wasn't Gonna Tell Nobody flits over Cone's personal life to instead give us a primer in Conesian apologetics. Cone devotes the first half of the book to outlining both his articulation of black theology and the obstacles he overcame to get it into print. In the second half, he answers his critics before concluding with a stellar — albeit somewhat incongruous — ode to writer and activist James Baldwin.

Given how extensively Cone's black theology has been spelled out over 49 years and 11 books, a text featuring James Cone the man, rather than James Cone the academic, would have been a welcome change. After all, he hasn't published a memoir since 1986. What was he thinking as he faced death? What questions did he have? What answers? (Perhaps it's a sign of these Instagram times that we think we even have the right to know.)

Yet, if readers squint hard enough, they can pry out from between the lines some idea of what may have consumed Cone in his last days. For instance, in the section where he answers womanist criticisms, Cone seems to wrestle with the realization that his beloved black theology lacked true inclusion — that he, in fact, was not immune from the misogynoir that marked many of the first pro-black movements in the United States.

Cone hails Delores Williams, a former student, as "brilliant," claiming that no one offered a sharper or truer criticism of his work. He claims that at the time when Williams and other up-and-coming womanist theologians were perfecting their ideas under his tutelage, he was not ready to hear what he needed to hear. He admits he still does not have answers to womanist concerns about the glorification of suffering, an idea central to his theology, but one that has been used to excuse the abuse of black women for centuries.

Unfortunately, Cone ultimately doubles down on his theory of redemptive suffering, dismissing Williams and other womanists for not having the "spiritual depth of Southern black religion" that shaped his own cross-centered theology.

Advertisement

It's interesting that Cone's response to womanist thinkers — many of them theological giants in their own right — comes in a chapter dedicated to what he's learned from his students, which is a separate chapter from the one in which he chronicles what he's learned from his critics. Perhaps there were structural reasons for this, but it's hard to shake the sense that he never really learned to see these women as his peers.

Still, Said I Wasn't Gonna Tell Nobody is likely to be an informative read for the young secularists still wondering when the old-guard black church is going to show up in the Black Lives Matter movement. Seeing Cone equate the deaths of Sandra Bland and Tamir Rice with those of Nat Turner and thousands of lynching victims should mean something to them.

It's also likely to be well-received by longtime fans of Cone's work; the overview of how black theology came to be, of Cone's own motivations and lessons in crafting it provide a neat coda for his illustrious career. But if readers are looking for a deeply personal book, they will be disappointed.

For all the work Cone did in learning how to remove the "mask" he wore in order to keep the boat steady in white, professional settings — code-switching, as it were — in this last book, he fails to remove the mask that makes him a human being and not just a public figure.

[Dawn Araujo-Hawkins is Global Sisters Report staff writer. Her email address is daraujo@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter: @dawn_cherie.]