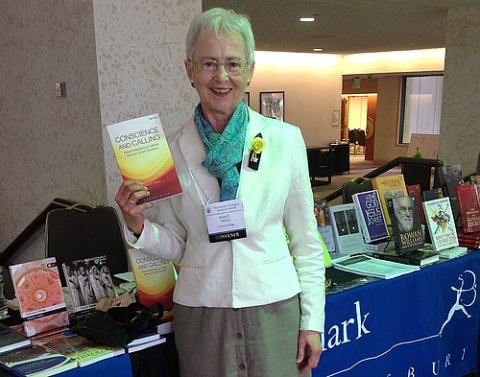

Sr. Anne E. Patrick holds up her 2013 book, "Conscience and Calling: Ethical Reflections on Catholic Women's Church Vocations." (Courtesy of The Women’s Alliance for Theology, Ethics and Ritual or WATER)

On April 5, 2018, on what would have been Sr. Anne E. Patrick's 77th birthday*, a group of friends and fellow scholars gathered to honor the distinguished feminist scholar and Sister of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary who had died July 21, 2016. The panel was comprised of Heather Dubrow of Fordham University, Jesuit Fr. David Hollenbach of Georgetown University, Leo Lefebure, also of Georgetown, and Susan Ross of Loyola University Chicago. Moderated by Julia Lamm of Georgetown, the panel reflected pointedly and poignantly on Patrick’s posthumously published On Being Unfinished: Collected Writings (Orbis). I offered the following introduction:

Come, Spirit of God, gather us here together to remember and to invoke and to celebrate one of your wonders.

Born in the old Georgetown Hospital just down the hill from where we now sit, Anne Estelle Patrick was the eldest of six sisters, grew up happily in Takoma Park, Maryland, and entered the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary in 1958 "to become a sister." It was not until 1969 that she completed her BA and 1982 her doctorate at the University of Chicago. Who can say it better than Fr. Charlie Curran: she was a gentle woman with a spine of steel.

Anne was, as a friend recently wrote me, "a woman of grace in every way." To know her was to love her. Her graceful writing, nurtured by her love of literature, matched a commitment to precision with passion for the truth. She took her love of literature and brought it into her work in ethics. "Aesthetics arrived in moral theology via Anne," says Jesuit Fr. James Keenan of Boston College. "The narrative replaced the case." And her profound respect for every human person never allowed the person to be seen alone but always rather in community. Her very method, says St. Joseph Sr. Elizabeth Johnson of Fordham, "was rooted in a profound reverence for the human person and [the person’s] experience, seeing in this the work of the Spirit of God. She … saw the person in a social context rather than [as] a free-standing individual, so her analysis focused on a whole, large picture."

Advertisement

She became, of course, a feminist moral theologian, but fully in practice as well as in theory, addressing some of the most sensitive issues issues on the Catholic docket — sensitively. Conscience was a particular center of her concern, and Charlie Curran goes so far as to say that important as was Bernard Haering's insistence that conscience must be free and faithful, Anne's "understanding of conscience as a creatively responsible self is a more helpful understanding." (It was the H. Richard Niebuhr influence, deepened by her own personal experience.) She likewise held a finely crafted position on prophecy, living it for others to see but speaking also hopefully of the "planned obsolescence" of the feminist agenda when equality had been achieved.

Many of us have favorite stories about Anne. One of mine is of our speaking on the phone the night we learned that Anne Carr had died. We were both deeply distressed. She wisely reminded me of a poem by Emily Dickinson. And I found myself saying, "Anne, you know that I've loved you for many years. But tonight [across the miles to Minnesota] I love you more than ever before." It was for me the beginning of an experience of Pentecost unique in my life.

But a still more favorite, and public, memory is of Anne in 1967 making a 30-day Ignatian retreat and reading the documents of Vatican II in the Walter Abbot translation. Schooled in poverty by her religious community, the book was the first she had possessed since 1958 that spoke so directly to her life and aspirations — and she felt emboldened to underline the passages she most wanted to return to. The paperback book cost 95 cents. And she had not yet completed her BA.

One of the most charming essays in the collection we consider tonight, giving the book as a whole its title, is "On Being Unfinished (De Imperfectione)." It speaks immediately to each of us in this room, as Anne reflects on a beloved image showing two Navajo women weaving a rug. How lovely, she muses, is the work in its making itself, not only in what, with many more hours of labor, it could come to be.

But let me call attention to a further sense of the beautifully unfinished, not simply in the process but in its final state. For, since the Renaissance, work that an artist — think Donatello or Michelangelo — considered finished, even though it may look incomplete, has been praised as "non finito." For the two great sculptors, as later for painters from Titian to Cezanne, the non finito can mysteriously open to the infinito. In our beloved friend Anne Patrick, who believed that theology and art each required the other, we have a patron saint for graced daughters and sons of God with "unfinished" lives. Here she is invisibly among us: This patron saint of the "non finito," author of a life that she herself, I feel confident, modestly deemed incomplete, but whom God, through her Spirit of wisdom, reveals to us now as perfected in glory.

* An earlier version of this story provided an incorrect date.

[Jesuit Fr. Leo O'Donovan is president emeritus of Georgetown University.]