“I will announce what has lain hidden since the foundation of the world” (Matt 13:35).

Sixteenth Sunday of the Year

Wis 12:13, 16-19; Ps 86; Rom 8:26-27: Matt 13: 14-43

In today’s Gospel, Jesus quotes the Prophet Isaiah and Psalm 78 to explain why he teaches with parables. He is drawing from a deep tradition within the Scriptures to show that its mysteries can only be approached in layers. Some of Jesus’ parables first appear to be simple lessons from nature about seeds and growth, rising dough, wheat and weeds. But a more careful reading reveals an unfathomable and challenging depth of meaning. As a teaching method, Jesus is inviting his audience to listen at deeper and deeper levels to the mystery of God’s Kingdom in their lives. There are secrets there “hidden since the foundation of the world” (Ps 78:2).

Of the many books on the parables, Hear Then the Parable, the 1989 classic by Bernard Brandon Scott (Fortress Press), explores some of these secret and often subversive lessons. For example, the mustard bush was a scourge to farmers, a rapidly spreading weed whose seeds were dispersed into the wind, attracting birds near the fields. Jesus makes it a symbol of the Kingdom of God as a parody of the mighty Cedar of Lebanon where eagles nest, a heralded image of the royal kingdom of Israel. Jesus’ kingdom, in contrast, was invasive and troublesome, attracting the hungry and the poor.

Or the unconventional highlighting of a woman in the Parable of the Yeast. The mysterious enzyme that grew in a moist rag kept in the dark place between baking days was the source of fresh bread when mixed with flour and oil. This was women’s work, the feminine miracle of life that sustained the community. Jesus’ kingdom was like that.

The original parables took on a life of their own. Jesus’ image of a field sown with both wheat and weeds was no doubt an appeal for patience and tolerance in a world beset by both good and bad. Jesus’ kingdom was not the victory of righteousness over sinners, but an incubator for reconciliation. A generation later, Matthew found this parable the perfect lesson for his fractious community in Antioch, in which Jewish and Gentile converts were proposing the rooting up of one another to preserve orthodoxy. The long interpretation of the parable is certainly an addition to the original, timely if not dramatic in promising future judgment to satisfy both camps.

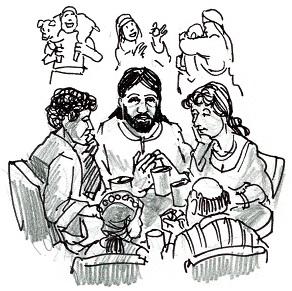

The parables invite us to stay with their imagery long enough to find the challenges. Some are extravagant to the point of absurdity, like the story of the shepherd who leaves 99 sheep to search for a single lost sheep. No earthly shepherd would do that, but your Heavenly Father is no ordinary shepherd. Other parables, like the steward who gives away the store or the father who welcomes back his debauched son, seem designed to offend logic and social honor. Jesus did both by stretching the rules and contaminating himself with public sinners as a sign of God’s mercy.

The key to most parables is Jesus’ personal relationship with his greatest parable of all, the Abba he communed with continually, the source of all his teaching and the God he was trying to reveal to anyone who would listen with ears that heard and a heart open to divine compassion. This was the mystery that had lain hidden since the foundation of the world.

Advertisement