A poll worker puts out a "Vote Here" sign at a Phoenix polling location for the midterm elections Nov. 8, 2022. (CNS/Reuters/Brian Snyder)

Election politics is always interesting for many reasons. But near the top of the list is the interplay in every election between foundational, demographic issues and quotidian ones, between underlying shifts in the electorate's makeup and views versus the news of the day. No one gets to the finish line without having slipped on a banana peel at some point, and the winner is usually the person who got up the most quickly and carried on. That is only true if a given candidate's message resonated with a changing electorate enough that they were motivated to vote. This interplay of the tectonic with the momentary requires observers to assign the proper values to each.

There appear to be three outstanding issues that could go well or poorly for the Democrats in ways that significantly help or harm their chances: the president's health, the nation's economy and the war in Ukraine. We shall examine these another day. And, of course, no one can predict what unforeseen event might intrude in the campaign. Today, however, I want to highlight a couple of recent articles that point to some of the foundational, demographic challenges and opportunities facing the Democrats.

The first article, by editors Charlie Mahtesian and Madi Alexander at Politico, looked at the rise of college towns in the Democratic coalition. They write, "In state after state, fast-growing, traditionally liberal college counties like Dane are flexing their muscles, generating higher turnout and ever greater Democratic margins."

So, for example, in this past spring's special election for the Wisconsin Supreme Court, Dane County, home to the University of Wisconsin's main campus at Madison, was critical to the Democrats retaking control of the state's highest judicial body. "Turnout in Dane was higher than anywhere else in the state," Mahtesian and Alexander write. “And the Democratic margin of victory that delivered control of the nonpartisan court to liberals was even more lopsided than usual — and bigger than in any of the state's other 71 counties."

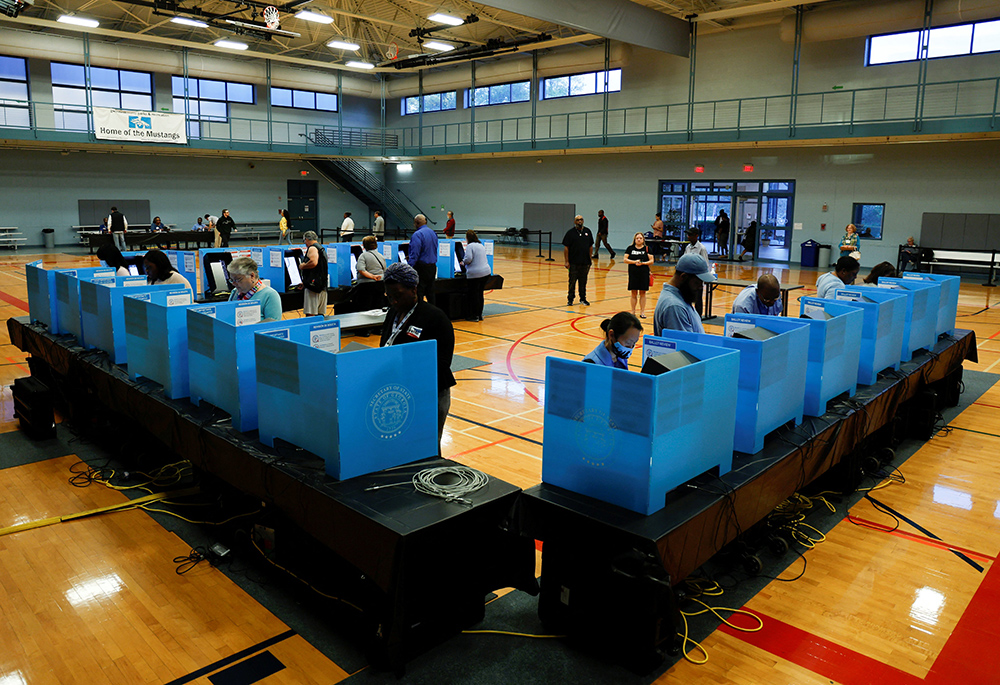

Suburban Atlanta voters in Gwinnett County vote in midterm and statewide elections at Lucky Shoals Park Nov. 8, 2022, in Norcross, Georgia. (CNS/Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)

The story is the same in Michigan:

Twenty years ago, the University of Michigan's Washtenaw County gave Democrat Al Gore what seemed to be a massive victory — a 60-36 percent win over Republican George W. Bush, marked by a margin of victory of roughly 34,000 votes. Yet that was peanuts compared to what happened in 2020. Biden won Washtenaw by close to 50 percentage points, with a winning margin of about 101,000 votes. If Washtenaw had produced the same vote margin four years earlier, Hillary Clinton would have won Michigan, a state that played a prominent role in putting Donald Trump in the White House.

If Trump's ability to energize working-class people who had not voted in years helped him conquer the "blue wall" in the Midwest, winning Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin in 2016, these college towns are rebuilding the blue wall. It is this phenomenon that also makes North Carolina a toss-up every four years: In 2000, George W. Bush netted 12,000 votes from the nine counties with college towns in the Tarheel State, winning overall by 13 points. In 2020, those same nine counties delivered a net margin of 222,000 votes for Biden, who lost the state by 1.3 percentage points.

Some of these changes have to do with college towns, known for rating high on livability indices, attracting newcomers, but a large part of the change has to do with old-fashioned organizing, of getting both the newcomers and the students registered to vote and then to the polls on Election Day.

Advertisement

"It's not a very sexy story. It's a lot of hard work that we're doing over a long period of time," Alexia Sabor, Dane County Democratic chair, told Politico. "The county party helps to organize a network of 20 neighborhood grassroots action teams. We fund them, we provide them with offices during election seasons, we give them money for websites, Mailchimp [an email marketing platform], volunteer recruitment events, volunteer thank-you events, whatever supplies they need — paper, printers, lighting — to run their team."

If college towns, and efforts to organize voters there, are putting some wind in the Democrats' sails, another group of voters is becoming more problematic: Latinos. Trump improved his standing among Hispanic voters between 2016 and 2020 by large margins, and not just in Florida.

"Trump improved his performance among Hispanics by 20 points in Wisconsin, 18 points in Texas and Nevada, 12 points in Pennsylvania and Arizona and among urban Hispanics in Chicago, New York and Houston," columnist Ruy Teixeira explained in The Washington Post. "In Chicago's predominantly Hispanic precincts, Trump improved his raw vote by 45 percent over 2016."

Today, Latino voters track with the rest of the electorate in rating Biden's performance on the economy worse than Trump's. These poll numbers should improve with the economy, and as Biden does a better job articulating his economic successes.

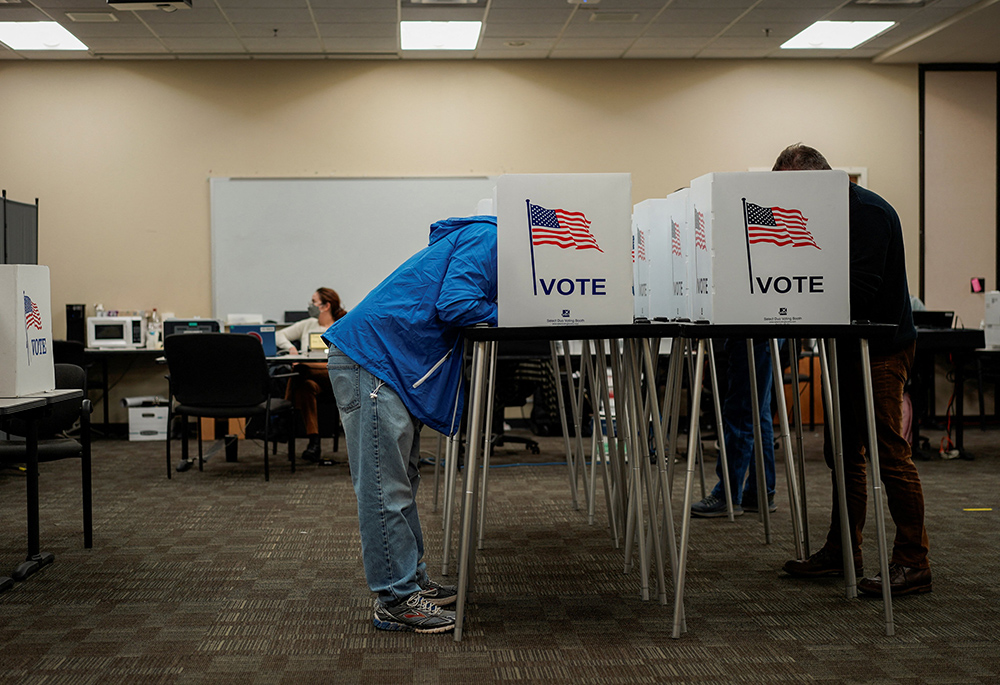

People in Las Cruces, New Mexico, vote early Oct. 24, 2022, for the upcoming midterm elections. (CNS/Reuters/Paul Ratje)

But Teixeira points to another problem, "an emerging gulf between the cultural outlook of many Hispanics and the increasingly left-wing values of the Democratic Party." On issue after issue, from transgender athletes to structural racism to American "greatness" and using fossil fuels, Latinos do not embrace progressive orthodoxy. So, for example, the American Enterprise Institute's Survey Center on American Life, with a large pool of 6,000 respondents, found that 60% of Latinos said racism comes "from individuals who hold racist views, not from our society and institutions" and only 39% agreed with the statement that racism is "built into our society, including into its policies and institutions." White, college-educated liberals, on the other hand, choose the structural reply by 81% to 19%.

There's the rub. It may make sense to double down on culture war progressive values when trying to gin up the base in college towns, even if it risks alienating white, working-class voters. The latter is a declining demographic. Latinos are not declining. They account for 54% of all population growth in the U.S. since 2000. Currently 19% of the population, Hispanics are projected to account for 28% of the U.S. population by 2060. Democrats can't afford to lose more Latino voters.

Teixeira explains how the Democrats can hold on to the Latino vote. "The challenge for Democrats is this: The party can no longer rely on simply mobilizing this constituency," he writes. "They will have to convince these voters that Democrats share the values of a community that is socially moderate-to-conservative, upwardly mobile and patriotic with down-to-earth concerns focused on jobs, the economy, health care, good schools and public safety."

How Democrats finesse these two underlying, at times conflicting, demographic developments — the growth of college towns and of the Hispanic vote — will set the foundations for the 2024 election cycle and beyond.