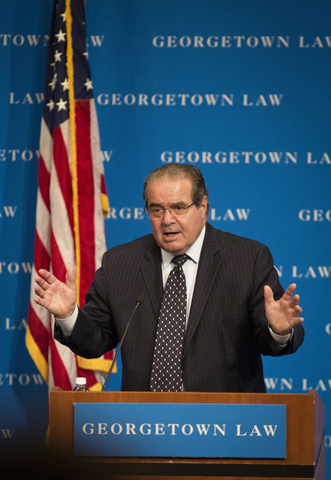

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia in a CNS 2013 file photo at Georgetown University Law Center in Washington (CNS/Nancy Phelan Wiechec)

Justice Antonin Scalia sat on the U.S. Supreme Court for almost thirty years. By standard measures, he was not the most influential justice: When litigators before the high court prepare their arguments, they usually target Justice Anthony Kennedy, not Scalia, because it is Kennedy who is likely to be the swing vote. But, Scalia became the face of a conservative legal movement that not only confronted dominant liberal legal attitudes and perspectives, but also revolutionized what it meant to be a conservative justice. In so doing, the man who thought the court should play a small role in a democracy helped accelerate the transformation of the court into a political football.

Even those of us who disagreed with Scalia found ourselves chuckling at his acerbic questioning and bon mots in dissent. His friendship with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a constant testimony to the belief, the humane belief, that there are more important things than politics. Fred Rotondaro, chair of Catholics in Alliance for the Common Good, told me yesterday, "I had the good fortune to know and be a friend of Justice Scalia for some 30 years. We agreed on virtually nothing politically but had fun lunches, almost always over Italian food and wine, talking often about Catholic thinkers like Chesterton. On the occasions we would move into political issues, he would needle me without mercy on my left wing politics." Washington has too few friendships like that anymore.

Nonetheless, there is no escaping a verdict on his influence on American jurisprudence, and that verdict is not affected by the fact that he was a good buddy to prominent liberals. He was an advocate of two judicial ideologies, neither of which is intellectually tenable and which conflict with each other. Originalism was Scalia’s core ideological commitment, the idea that the Constitution should be interpreted as it was understood at the time of its ratification. He employed Originalism to question the idea that the Constitution is a "living document," as liberal jurists held.

To be sure, there was a need for a conservative corrective after the high court starting snooping around the “penumbras” of the Constitution. As Justice Elena Kagan said in mourning Scalia’s death, “His views on interpreting texts have changed the way all of us think and talk about the law.” But, whether the Constitution is alive or not, the people whose government it intends to frame are most certainly alive and their circumstances change. Laws that cannot change with the lived circumstances of a people soon become disconnected from reality, and that disconnect will lead to the law being held in derision or ignored.

Nowhere did we see the limits of Originalism more than in his decision in Heller, which struck down both a D.C. ban on handguns and a requirement for trigger locks on all other guns. The Second Amendment, Scalia argued, gave individuals a near-absolute right to bear arms, although he allowed that felons and the mentally ill could be prevented from exercising this right. When the Second Amendment was drafted, the world was a different place. As the Brookings Institution’s Ben Wittes has written:

There are lots of good reasons why our values today might not coincide with those of the Founders on the question of guns. The weapons available today, for one thing, are a far cry from muskets, which could never have yielded the kind of street violence America sees routinely now. On a more esoteric level, the Second Amendment's protection for militias reflected the importance the Founders attached to an armed citizenry as a protection against tyrannical government. This made sense at the time. The Founders had a lot of experience with oppressive rulers and little idea whether the constitutional order they were setting up would remain free; maybe they would need to overthrow it sometime. After more than two centuries of constitutional government, however, it's safe to assume that neither an armed citizenry nor a well-regulated militia really is "necessary to the security of a free State." The opposite seems closer to the truth; just ask the Bosnians or the Iraqis. And elections, it turns out, do the job pretty well. To put the matter simply, the Founders were wrong about the importance of guns to a free society.

This is what Scalia, and his acolytes, can’t admit: That as a matter of “original” historic facticity, the Founders could only assert a right to bear a musket, not a right to bear an assault rifle, because that was all they knew at the time. Nor do we today fear that a standing army is a threat to the Republic. So, it is hard to see how the original intent of the Founders mandated Scalia’s finding in Heller. And, whither his concern to defer to the political branches?

Scalia’s other ideological commitment was to Textualism, the idea that the actual words must be interpreted in a kind of fundamentalist manner. This could conflict with Originalism. For example, an originalist would, like an historian, search for explanations as to what was intended by the drafters of a given text, to confirm that original intent and guarantee against latter day misinterpretations. But, Scalia famously loathed citations to legislative history. Textualism rests on the supposition that the Constitution is a self-interpreting text and if that were true, why would we need a Supreme Court? In practice, Textualism resulted in the conclusion that any given text meant exactly what Antonin Scalia thought it meant.

Originalism and Textualism, then, could be employed as needed to reach a desired result. Think Bush v. Gore, in which Scalia overlooked the fact that elections are run by the states, and subject to oversight by state courts. Or consider last year’s Affordable Care Act case, in which Scalia scorned analysis of legislative intent, and vitiated the traditional conservative position that a part of a statute should be interpreted within the context of the whole of a statute. Perhaps, Scalia was not an ideologue, simply a politician on the bench who found conflicting ideologies useful at different times to attain the results he desired?

Before Scalia’s tenure, a conservative jurist was one committed to stare decisis and deference to the political branches. But in Citizens United Scalia joined with the other conservative justices to overturn decades of rulings, and ignored the stated desire of the political branches. Indeed, the court even invited the litigants to argue issues not essential to the adjudication of the case so that they could reach a more sweeping decision. There was nothing conservative about it in any traditional meaning of the word conservative.

I have used the word "ideology" with intent. Of course, all jurists operate with some kind of judicial philosophy. All of us try to make sense of the world, to reconcile our thoughts and experiences into a coherent, or largely coherent, whole. But, if philosophy suggests thinking and thinking again, ideology is not supple or pliable. I can illustrate the difference by reference to an event in the spring of 1941. A fascist revolt had taken place in Iraq. The Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in the Middle East, General Archibald Wavell, declined to send the few brigades necessary to put down the revolt because he did not want to disperse any of his forces from the front on the Libyan-Egyptian border. The War Cabinet in London overruled him, something they rarely did. The brigades were sent, the revolt was put down and the Nazis were denied a potentially devastating outpost that would have drastically altered the balance of power in that region. Writing about the incident in his war memoirs, Churchill observed:

We often hear military experts inculcate the doctrine of giving priority to the decisive theatre. There is a lot in this. But in war this principle, like all others, is governed by facts and circumstances; otherwise strategy would be too easy. It would become a drill-book and not an art; it would depend upon rules and not on an instructed and fortunate judgment of the proportions of an ever-changing scene.

This seems relevant to jurisprudence too. Scalia's blending of Originalism and Textualism made interpretation "too easy."

Many biographers and legal scholars will be needed to determine whether Scalia was an ideologue or whether he used ideology the way liberal jurists use concepts and phrases that Scalia derided. (Future jurists will decide whether his influence outlives the man, a subject to which we will turn tomorrow.) He was less consistent than he claimed and was certainly capable of achieving a desired result by vitiating one set of principles for another. He legislated from the bench when it suited his purposes. He chose not to defer to the political branches when it suited his purposes. If you shared his purposes he was not just a giant but a great jurist. If you did not, he was still a giant, but the verdict on his jurisprudence belongs now to the historians and the next generation of Supreme Court justices.