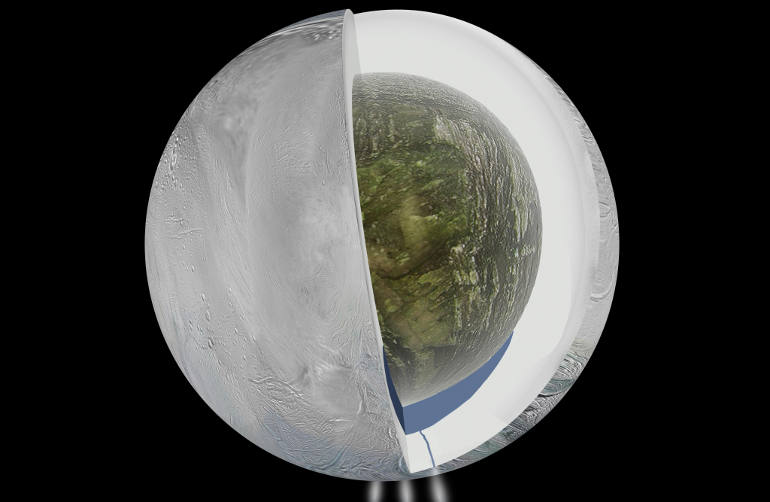

A diagram illustrates how gravity measurements by NASA's Cassini spacecraft and Deep Space Network suggest that Saturn's moon Enceladus, which has jets of water vapor and ice gushing from its south pole, also harbors a large interior ocean beneath an ice shell. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

“And God made the two great luminaries, the greater luminary to dominate the day and the lesser luminary to dominate the night; and the stars.” (Gen. 1:16)

During the month of April, Christians throughout the world celebrate Jesus’ resurrection and the promise of eternal life. This particular April also brought two astronomical discoveries that raise the question of life beyond the planet Earth.

The journal Science published a report (subscription required) April 4 in which planetary scientists confirmed a Lake Superior-sized body of water on Enceladus, one of Saturn’s moons. Two weeks later, astronomers detailed in the magazine their discovery of Kepler-186f, an Earth-like planet within a seemingly habitable zone of space. Both Enceladus and Kepler-186f harbor the possibility of life.

Scientists have suspected since 2005 that Enceladus held water underneath its icy surface -- that year, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft photographed geysers spitting out ice crystals on this tiny moon.

Enceladus cannot stay warm on its own, however, so the presence of liquid water existing on an frozen space-rock was a long shot. Cassini continued to photograph Enceladus, and scientists became increasingly puzzled by the presence of its active geysers. A mapping of Enceladus’ gravity field by Cassini helped solve the mystery, as gravity reveals mass. Sure enough, as NASA measured the moon’s varied mass via its gravitational force, it discovered water present under the ice.

In layman’s terms, Enceladus “is able to heat water to a liquid thanks to a gravitational love triangle that involves Saturn and another moon, Dione,” the Los Angeles Times explained. That gravitational pull “squeezes and stretches [Enceladus] -- and all that kneading from this tidal distortion heats it up, melting some of the water ice inside.”

Christopher McKay, a NASA planetary scientist, told The New York Times in early April that only Enceladus so far is known to possess the four essential ingredients for life (as known on Earth): liquid water, energy, carbon and nitrogen.

Now, many scientists would like to remove samples from Enceladus to see if life is in fact present -- Little green men are not likely, but little microbes? Maybe.

But this dream presents big challenges. How and what will remove such delicate samples? How will these samples journey back to Earth intact, or possibly alive? How would NASA even fund such a mission with its ever-dwindling budget? And as if taken from a science fiction novel, what precautions would be necessary, as the NY Times puts it, to prevent any alien life infecting Earth?

Harvesting samples seems less likely from Kepler-186f, which resides in the Milky Way, about 500 light-years from Earth.

But what makes Kepler-186f -- named after the Kepler Space Telescope, which famously has detected close to 1,000 exoplanets since 2009 -- special is its striking similarity to our own planet: a radius only 10 percent larger than Earth’s, and the outermost planet in a five-planet system orbiting a cool dwarf star about half the size of our sun.

Scientists have joked that Kepler-186f’s sun and its distance from it places the planet in a

“Goldilocks” zone – not too hot or too cold. But the scientific world has viewed the planet’s discovery as historical, since the planet may have the two basic prerequisites for life: a rocky rather than gaseous surface, and the potential to support liquid water.

When Kepler began in 2009 hunting for planets, the Vatican Observatory and the Pontifical Academy of Sciences sponsored an astrobiology conference focusing on the possibility of extraterrestrial life. That the Pontifical Academy of Sciences hosted “a meeting on this frontier topic” was appropriate, observed Chris Impey, astronomy professor at the University of Arizona and presenter at the conference.

“The motivations and methodologies might differ, but both science and religion posit life as a special outcome of a vast and mostly inhospitable universe,” he told Zenit.org.

At the conference, one presenter, Athena Coustenis, a planetary scientist at the Paris-Meudon Observatory in France, invoked Enceladus.

Coustenis described how the moon was “spitting out its guts with water, liquid water, water vapor, organics and ammonia in these huge plumes extending more than 250 miles into space,” and surmised that the jets originated in an underground, liquid water ocean – an indication that Enceladus possessed the ingredients for life.

After God spoke to Abraham in a vision (Gen. 15:1), God made Himself known and presented Himself to Abraham as in the days of Eden: And He took him outside, and said, ‘Gaze, now, toward the Heavens, and count the stars if you are able to count them!’ And He said to him, ‘So shall your offspring be!’” (Gen. 15: 5).

In Hebrew the verb gaze suggests looking down from above, and the rabbis explain that God actually took Abraham up into space, who then had the privilege of gazing down into the universe.

If we do discover extraterrestrial life, these verses of Genesis will take on a whole new meaning. Did God reveal to Abraham not only his offspring on Earth, but also Abraham’s connectedness with life on an array of moons and planets?

Only time, and scientific exploration, will tell.