Almost nine years ago I did a column titled "The Pope's New Man in New York" (June 5, 2000). The title was taken from the front-page headline in the New York Post, the day after the Vatican announced the appointment of Edward Egan as the next archbishop of New York.

Egan was bishop of the diocese of Bridgeport, Conn., at the time, and succeeded Cardinal John O'Connor, who, like every other bishop and archbishop of New York before him over a period of some 200 years, had died in office.

Cardinal Egan had submitted his resignation upon turning 75 over a year ago, but it had not been accepted until last month, when Pope Benedict XVI named Timothy Dolan, archbishop of Milwaukee, to become the new archbishop of New York.

I noted in that earlier column that throughout most of the history of the Catholic church, bishops were elected from the local diocesan clergy, by laity and clergy alike. The Bishop of Rome had no direct role whatever in those elections.

However, because of the communion that existed, and still exists, among all the local churches, or dioceses, both with one another and with the diocese of Rome and its bishop, the pope was subsequently informed of the results of these elections as a matter of courtesy and protocol.

It was not until the 19th century, however, that the popes began to claim the exclusive right to appoint bishops throughout the Catholic world, including major cities like New York. Although the pope has exercised this prerogative ever since then, it is hardly traditional.

First millennial Catholics would have been taken aback by the papal appointment of bishops, but they would have been utterly shocked to learn that someone who was already the bishop of one diocese would accept election to another.

Such a practice would have been recognized as in direct violation of the teaching of the First Council of Nicaea in 325 (a council that defined the divinity of Jesus Christ and gave us the Nicene Creed). Nicaea's teaching was reaffirmed by the Council of Chalcedon in 451 (a council that defined the relationship between the divinity and humanity of Christ).

Canon 15 of Nicaea read as follows: "On account of the great disturbance and the factions which are caused, it is decreed that the custom, if it is found to exist in some parts contrary to the canon, shall be totally suppressed, so that neither bishops nor presbyters [priests] nor deacons shall transfer from city to city.

"If after this decision of this holy and great synod anyone shall attempt such a thing, or shall lend himself to such a proceeding, the arrangement shall be totally annulled, and he shall be restored to the church of which he was ordained bishop or presbyter or deacon."

The Council of Chalcedon, 126 years later, reiterated the teaching of Nicaea in its own canon 6: "In the matter of bishops or clerics who move from city to city, it has been decided that the canons issued by the holy fathers concerning them should retain their proper force."

These two canons, which have never been explicitly revoked, were consistently regarded as retaining "their proper force" as late as the year 897, when the body of Pope Formosus (891-96) was exhumed from its resting place nine months after his death. The body was clothed in full pontifical vestments and placed on trial in what became known as the "cadaver synod."

Among the charges leveled against the deceased pope was that he had accepted election as bishop of Rome when he was already the bishop of another diocese (Porto, in Italy), in clear violation of the canons of the councils of Nicaea and Chalcedon.

It is significant, however, that no known protest had been registered at the time of his election to Rome, nor was there any known reaction when Marinus became the first bishop of another diocese (Caere, now Cerveteri) to be elected bishop of Rome in 882.

The force of these canons obviously did not endure into the Second or Third Christian Millennia, when the practice of transferring bishops from one diocese to another became common.

In our own time, a certain type of Catholic pines for "the good old days" before the Second Vatican Council when, it is mistakenly thought, the Lord's "organizational plan" for his church was faithfully honored and implemented.

But we realize now, in the light of history, that what people had become accustomed to in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s was not at all a part of the unchanging tradition of the Catholic church.

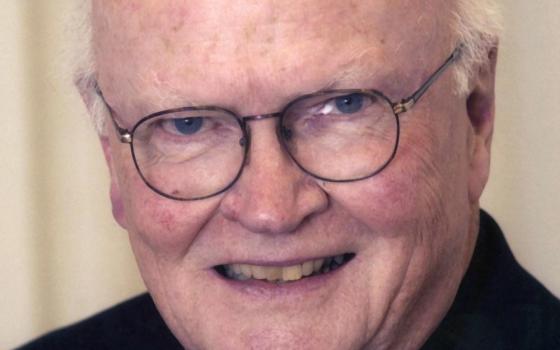

© 2009 Richard P. McBrien. All rights reserved. Fr. McBrien is the Crowley-O'Brien Professor of Theology at the University of Notre Dame.