People make their way by boat past a church along a flooded road in Bulacan, Philippines, Aug. 21, 2013, following heavy monsoon rains. (CNS/Reuters/Erik de Castro)

Here in the Northern Great Lakes Basin, watching weather is a part of everyone's life. It's essential for living in remote, rural environments. During road trips in winter storms, for us it can mean the difference between life and death.

Troubling trends in recent years, framed by warnings from global experts, suggest changes in temperature and rainfall are now bringing unprecedented transitions to our region's forests and waterways. For those able to connect the dots, there are plenty of worrisome implications for human health.

In his latest book, Philip Jenkins, whom The Economist magazine calls "one of America's best scholars of religion," takes a deep dive into religion and science to explore global weather changes and what they mean for communities of faith. He concludes Climate, Catastrophe, and Faith: How Changes in Climate Drive Religious Upheaval with a haunting prediction.

It's no casual read. And Jenkins has done his homework, with 392 footnotes, laying out his case in clear, orderly fashion. At the beginning of the book's first chapter, the author presents us with a quote from Voltaire: "Three things exercise a constant influence over the minds of men: climate, government and religion. ... That is the only way of explaining the enigma of this world."

In his subsequent exploration of climate change and religion, Jenkins, currently distinguished professor of history at Baylor University, masterfully mines early American history, lifting up examples connecting storms to revivals, famine to witchcraft, and extended winters to cults and spiritual awakenings.

He rightfully acknowledges that in times of worldly crises, there's plenty of ambiguity in responses from the faith community.

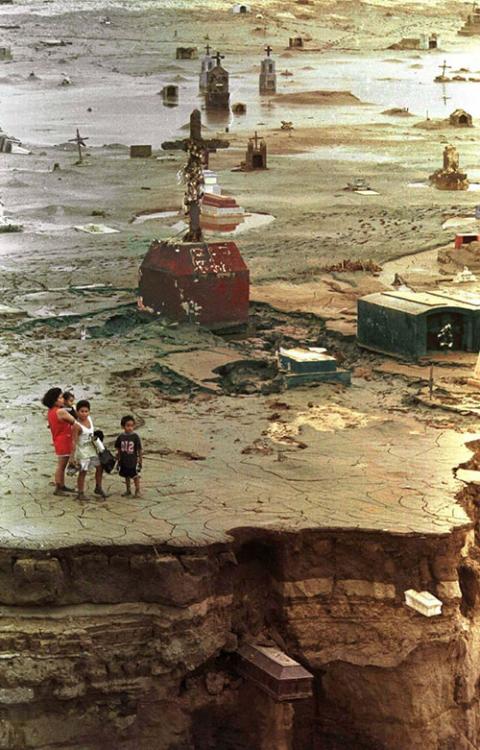

A family looks over a cemetery damaged by mudslides and flooding from El Niño rains in Trujillo, Peru, Feb. 12, 1998. (CNS/Reuters)

In some cases, the author writes, "religious groups take the lead in offering charity and relief to desperate populations, a function for which the state is usually inadequate."

But in truly threatening crises, Jenkins observes, mainstream institutions often are unable to offer any serious relief. Sects, cults and other spiritual movements that emerge in response to the crisis offer meaning, purpose and deep-seated measures of personal security to followers.

There are plenty of fascinating takeaways in Jenkins' historical and scientific overview of climate changes around the planet.

The Asian monsoon season, he writes, is arguably "the Earth's largest and most important climate phenomenon, influencing the livelihood of over 60 percent of the world's population."

His description of El Niño (Spanish for "the child," a reference to the Christ Child because it was often observed in December) provides readers with a basic science-history lesson that won't be forgotten.

Peruvian scholars first saw El Niño as a regional weather phenomenon primarily restricted to Central and South America, Jenkins explains, but the global scientific community now recognizes its extensive impact around the entire planet.

That's another reminder for the noninitiated among us: Everything is connected.

In his captivating historical review, Jenkins highlights the effects of the "Little Ice Age," a nearly half-millennium cold period that reached its peak between the 17th and 19th centuries, which shaped weather patterns in Europe and North America.

He also informs us about "The Medieval Sun," a warmer period dating roughly from 1100 to 1250 that drove substantial economic and cultural growth across Europe by allowing longer growing seasons and more agricultural activity.

Europe's population was believed to have increased from between 35 million and 40 million to over 80 million in but a few generations. France's population alone grew from 9 million to 15 million between 1000 and 1250.

There's much to ponder in Jenkins' far-reaching study, from impacts of weather on Buddhist renewal movements in Korea and China centuries ago, to the mega El Niño of the 1980s that correlated with the rise of civil wars and guerrilla struggles in Central America and the Andes.

There, Jenkins reminds us, peasants were already living with marginal resources, tenuously dependent on water and seasonal soil conditions. No surprise that insurgent movements, like Peru's utopian Shining Path, provided new visions, framed in Maoist or Marxist terms, for the poor crushed by those circumstances.

Following his observations on history, the last chapters of the book are framed by a helpful historical review of the emerging consensus about the reality of climate warming.

In 1988, the climate scientist James Hanson of NASA made a historic presentation to the U.S. Senate. He was one of many scientists convinced of such a phenomenon but among the first to announce to government officials that "evidence was strong the greenhouse effect is here."

Advertisement

Jenkins searches for balance, perhaps reaching a bit too far to bow to critics who are convinced that human ingenuity and creativity will save the day. He acknowledges there are technological innovations that may mitigate the rising climate threat, that some parts of the planet will actually become more habitable, that human history has shown we are a fascinatingly adaptable species.

But he is rightfully cautious. He also knows that human ingenuity has its limits. The need for collective response and global cooperation will be vital. To what extent can we reenvision and creatively adapt to what will be coming? That stands as a yet-unanswered question.

In his conclusion, the author addresses the fractured social systems that currently serve as a foundation for market capitalism, and what this might mean for "salvaging a future."

There will be readers who will be grateful that he is hesitant to align himself too quickly with doomsday prophets, yet he holds a line about the urgency of what most climate scientists tell us lies ahead. Most pointedly: mass migrations.

Jenkins chillingly writes, "Within a few decades, between 1 and 3 billion people will find themselves in conditions too warm for comfortable survival outside the ecological niche in which most humans have survived for the last millennia."

The bitter irony is that those who will suffer most directly and harshly from global warming will be the most fragile nations in our global community. It is there, Jenkins tells us, that populations are growing.

Latitude, he predicts, will become a critical factor for human habitation. Much of what we know now as the tropics — those regions between 23 degrees north and 23 degrees south of the equator — will be insufferable. Unlike in North America and Europe, Jenkins reminds us, religion and spirituality those poorer, less-developed countries continue to flourish. They will continue to do so. And for good reason.

Those regions nearest the equator — Africa, Central America, South America and part of Asia, the area some historians call the "Global South" — will become, more and more, places of turmoil and migration.

They will also spark new expressions of spirituality, meaning and hope for their followers. The author warily suggests it won't be a neat package. We need to strap ourselves in. Get ready for the ride.

Jenkins closes with a dire warning: "God is far from dead, and He may yet return with faces that are comforting to his followers, but which outsiders might find stern and even terrifying."