Abandoned cars are seen in a flooded street Jan. 9 in east Santa Barbara, California. (OSV News/Reuters/Erica Urech)

When Brent Jaimes had to evacuate as water flooded into his St. Louis area home in July of 2022, his walker sank inches into the ground with every step he took. Jaimes doesn't remember who carried his wheelchair out of the house, but it made it into the evacuation boat along with his partner and his 19-year-old daughter, who evacuated with him, and emergency personnel.

Jaimes, an attorney who has POEMS syndrome, spent two nights in a hotel before he was able to return home. His friends helped rip out the peeling laminate flooring in his house to make the first floor accessible for using his mobility devices, and he was able to draw on Federal Emergency Management Agency funding and his homeowner construction experience to coordinate with contractors to repair the majority of the water damage within a month.

"This was not an easy set of circumstances," Jaimes said.

March data from the U.S. Census Bureau's Household Pulse Survey shows that, of people who had been displaced in the last year by a natural disaster, people who have a lot of difficulty walking or climbing stairs, like Jaimes, are more than three times more likely than people with no difficulty walking to experience unsanitary conditions one month after the disaster.

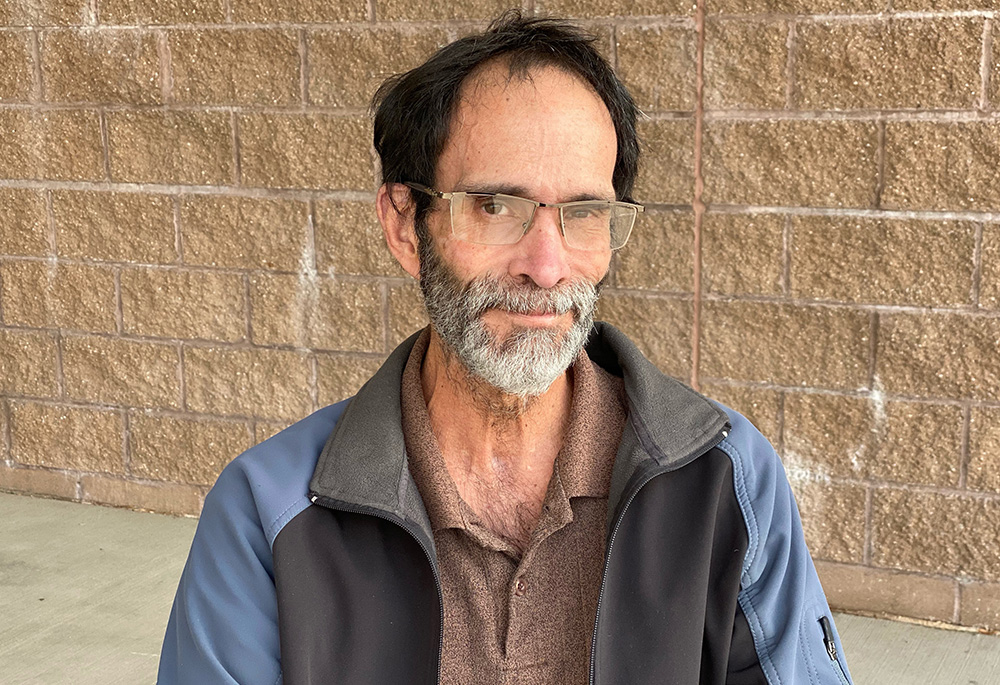

Brent Jaimes (Courtesy of Kathleen Corley)

About twenty-six percent of displaced people who have a lot of difficulty walking or climbing stairs reported experiencing "a lot" of unsanitary conditions a month after a disaster. For people who cannot walk at all, about 80% of them experienced similarly unsanitary conditions.

The Household Pulse Survey, which began measuring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020, added questions about natural disaster impacts on U.S. households in December 2022. The survey results have revealed dramatically worse outcomes for disabled people after natural disasters, including much higher levels of displacement, damage severity, loss of electricity, unsanitary conditions, food and drinkable water shortages, isolation, fear of crime and possible scam offers.

Shari Myers, the disaster operations coordinator for The Partnership for Inclusive Disaster Strategies, a disability-led nonprofit that runs a 24/7 disability and disaster hotline with information and resources, said the data was not surprising to the disability community. "This has been the way forever," she said.

Almost 33 years after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, Myers still has to remind emergency management professionals that there are no waivers to the law in a disaster.

A fire truck in a street at night are pictured in this photo of Brent Jaimes' experience with flooding at his St. Louis area home. (Courtesy of Kathleen Corley)

Myers connected the data to the affordable housing crisis in the U.S., where affordable housing that is also accessible is incredibly scarce. She said that people with disabilities frequently end up in hotels for long-term stays or in homeless shelters.

The Pulse Survey shows just how stark the differences are between disabled and nondisabled people's abilities to return home. For instance, according to March data of adults who were displaced due to natural disasters in the past year, about 73% of blind people never returned home after being displaced in a disaster, while only about 6% of sighted people never returned home.

As climate change increases severe weather events, Myers urged the U.S. to address low-income and accessible housing.

Shari Myers, disaster operations coordinator for The Partnership for Inclusive Disaster Strategies (Courtesy of Shari Myers)

A 2019 report by the National Council on Disability, an independent federal agency, highlighted another obstacle to returning home after a disaster. The report "found that people with disabilities are frequently institutionalized during and after disasters" and when previously independent disabled people are institutionalized, they often experience deteriorating health outcomes and difficulty returning to the community.

Sheltering in place poses its own risks. Myers said The Partnership for Inclusive Disaster Strategies helps people work through making that decision by considering factors like how long the disaster will likely last and what kind of resources a disabled person has for a power outage. She urged people to keep flashlights, a week's worth of nonperishable food, and water at home.

The decision about whether or not to evacuate has to be made quickly to use accessible transit. "The first thing that goes generally after an evacuation order has been declared is paratransit," said Myers.

Myers praised local, grassroots efforts to support disabled people who are sheltering in place.

"We are seeing a lot more organization of grassroots groups saying, 'We're not going to wait for emergency management. We're going to take care of our own,' " said Myers. "That's where it needs to be moving to."

Bethlehem Lutheran Church is pictured in this photo. The church is part of Together New Orleans' Community Lighthouse project, a network of churches and other community centers equipped with solar panels and backup batteries that can serve as disaster relief centers. (Courtesy of Together Louisiana/Carlos M. Silva Photography)

Together New Orleans, a coalition of congregations and community organizations, came to a similar conclusion as they reflected on the preventable deaths from heat illness and carbon monoxide poisoning from generators after 2021's Hurricane Ida.

"This happens time and time again," said Asia Ognibene, a Catholic who is leading disaster response for the coalition's Community Lighthouse project. "People were dying, and we were literally left helpless."

Together New Orleans decided to address the problem by forming Community Lighthouse, a network of churches and other community centers equipped with solar panels and backup batteries that can serve as disaster relief centers.

In the pilot phase, Together New Orleans fundraised for 16 sites in New Orleans, including a Catholic church, and 8 other sites in Louisiana. Currently three sites have solar panels, and Together New Orleans hopes to have the pilot phase built before hurricane season this year.

Ognibene said that churches in the Community Lighthouse project are assigned a turf around their church where they will perform an annual canvas, going door-to-door getting to know their neighbors and building a list of people who need to be checked on within 24 hours of a disaster or long-term power outage.

Asia Ognibene, who leads disaster response for Together New Orleans' Community Lighthouse project (Courtesy of Together Louisiana/Carlos M. Silva Photography)

That list would include people who would need batteries brought to them to power a CPAP machine or an oxygen tank. The project is working to secure necessary batteries for this purpose in addition to even larger batteries that could power small air conditioners.

Myers said that churches' exemption from the Americans with Disabilities Act can limit their ability to help their communities during a disaster. When she was national disability integration coordinator for the American Red Cross, Myers would encourage religious leaders at shelters to consider accessibility in their next capital improvement project.

Beyond the 24 sites in the pilot phase of Community Lighthouse, there are other locations that have indicated interest in participating if more grant funding comes through. Ognibene said that Community Lighthouse is using the CDC's social vulnerability index to select locations.

Although door-knocking isn't practical in "very rural" and "very spread out" Tehama County in northern California, Ruth Ann Rowen, a registered nurse and the emergency management coordinator for St. Elizabeth Community Hospital, said community engagement and outreach is crucial.

Rowen, a born-again Christian who has been at St. Elizabeth for 41 years, said, "If you don't know your community, you're dead in the water. I mean, you can't do this job if you don't know what the needs of your community are and who to reach out to to help them."

Rowen emphasized her collaboration and communication with emergency responders, the education system, and disability and community organizations. "It's whose phone number you have in your cellphone when the disaster hits," she said.

To connect with people with disabilities and older adults, Rowen participates in fairs where she shares supplies and preparedness information. She also partners with a local group of adults with developmental disabilities who have played patients in a hospital evacuation drill and county drills.

"Normalizing and including all types of people in our plans is healthy," said Rowen. She emphasized that it was important to listen to community members about their needs without presuppositions.

Pauline Castres, a disabled environmental activist based in the United Kingdom, told EarthBeat the disproportionate climate change impacts disabled people face around the world can be "long-term" and "traumatic."

Pauline Castres, environmental activist (Courtesy of Pauline Castres)

"There's very little data available on disability worldwide, but we know that there's a rippling effect as accessible aspects of infrastructure might not be rebuilt after an extreme climate event," she said.

"Disabled people aren't a monolith, and we need to take into account the fact that it's not just one type of needs we need to meet, but a wide range. And when we do, it also incidentally benefits many nondisabled people," she said.

Castres said that disabled people may be disengaged from climate action because of discrimination, poverty or the lack of intersectional inclusion in climate spaces.

"I want to tell disabled people that they are welcome and needed in this space. We need each and everyone one of you because climate change is one of the biggest threats to our rights and survival, and it cannot wait," said Castres.

"People with disabilities are subject matter experts in surviving and making things work," said Myers. "Don't plan for us, plan with us."