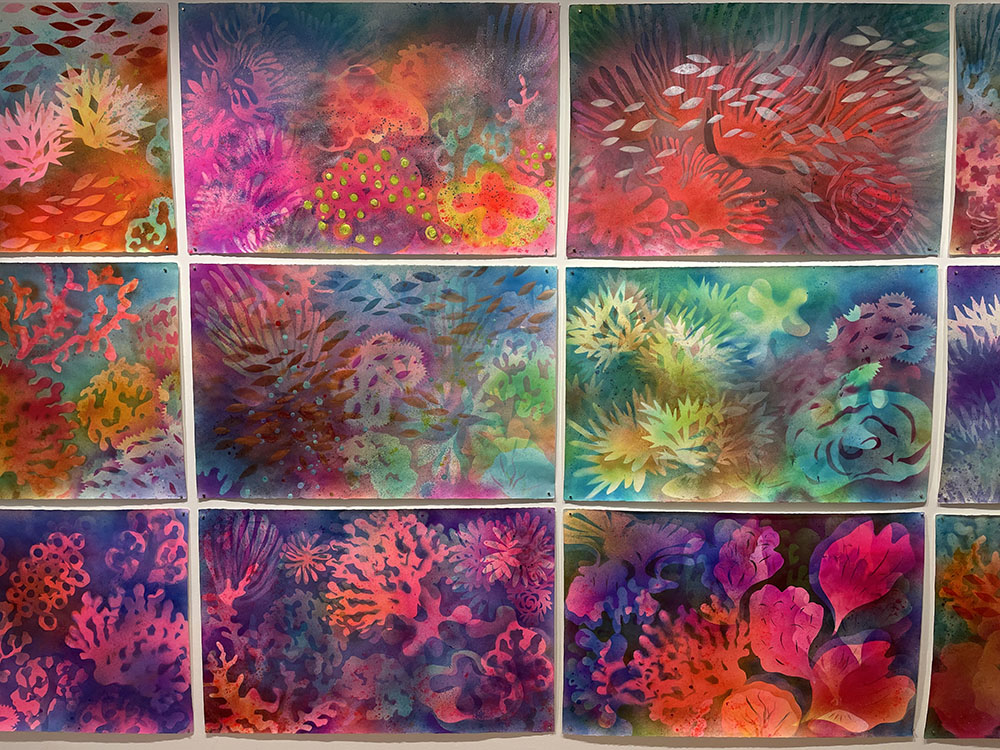

"Kaleidoscope of Coralscapes: Memento Mori" by Lois Bender (Photo by Jim McDermott)

In mid-December, 13 artists concerned about the global climate crisis staged a five-day pop-up art exhibition and conversation series at the Ceres Gallery in New York City. The exhibit, titled "Mayday! EAARTH," was the fifth exhibition that Marcia Annenberg has curated on the environment.

Annenberg's introduction as she took me around the exhibition was peppered with frightening facts about the state of our planet: one-third of Pakistan underwater this summer while other rivers around the world are drying up; the terrifying speed of storm surges today, like at Fort Meyers, Florida, during Hurricane Ian in September; deforestation in and around the Amazon rainforest is releasing the carbon stored in those trees' roots into the air, transforming what was a carbon sink area into a massive carbon source.

Many of the other artists I spoke to had their own horrifying details to add about traumas done to our planet that drive their passion to create environmentally themed work.

"From the time I graduated from high school in the 1970s to now, a quarter of American birds have gone extinct," Noreen Dresser told me.

"Rushing c22" by Noreen Dean Dresser (Photo by Jim McDermott)

The world's frogs are not far behind, Kathy Levine noted as we stood before a set of delicately-sculpted frogs on recycled paper made to look like wood. "Thirty percent of all frogs around the world are actually facing extinction," she shared. "They're one of the biggest groups of animals being affected. They're disappearing before our very eyes."

Susan Hoffmann Fishman's oil paintings offered a series of aerial views of the landscape around Siberia and the Dead Sea, where melting permafrost and sinking sea levels — a result of human overuse of the sea's water — are each causing numerous sinkholes. (There are 7,000 around the Dead Sea alone, Hoffman told me.) She painted the landscape around the Siberian holes in greens and oranges, as though the land itself is riven with pain.

Ann R. Shapiro's work seemed to express her own pain — consisting of digitized drawings, paintings and photographs which together depict a shadowy lobster boat against a nightmarish background of furious, unreal colors. "The more you read, the angrier I'm getting. Don't people understand what's happening? Don't we get it?" she asked. "We'll always have a landscape, no matter how high the water rises, how hot it gets. But what kind of world are you getting into?"

"Raging Climate 5, Ominous" by Ann R. Shapiro (Photo by Jim McDermott)

In addition to the eerily apocalyptic color palettes, a number of pieces involved the use of overlapping perspectives. Fishman's work gave an aerial view, yet within it certain areas were radically expanded.

Similarly, architect and artist Lisa Reindorf presented what looked to be a cityscape from above as sea levels rise. But as you stared at the work, the water pouring in from the left side of the image also looked like a wave crashing down. The crisis we're in is so dramatic, even the laws of physics seem to be collapsing.

But there was unexpected shelter to be found among this work, as well. Lois Bender's wall of undersea coral stencils glowed in brilliant reds and blues, greens and pinks and purples. And Bender's own commentary on the corals was equally radiant. "It was just fascinating to learn about the forms — there's the fan form, the bubble form, the brain form," she listed them, laughing with delight.

"The coral animal looks like a plant, like a vegetable because they stay put. But they're animals," she said with wonder.

Advertisement

I pointed out how unexpected it is to find hopeful work in an art exhibit about our climate emergency. "I wanted to show the beauty before it can become blight," Bender said.

"The irony is that sometimes disasters are beautiful. Corals fluoresce before they go white and die. That's the purple," she explained, pointing to one panel. "I wanted to do the corals in beautiful color. Maybe that'll inspire people to save it."

Angela Manno, who paints gorgeous icons of at-risk animal and plant species, sees her work portraying such things as sea turtles, birds and microscopic zooplankton as having a palliative quality, as well. "When we talk about all this destruction, how can you wrap your mind around it except to say that it is pathological?" she asked.

When you're doing icons, she explained, the process of creation gives the images themselves a far greater voice in that ongoing struggle. "As opposed to Western art, where the artist imposes themselves on the canvas," she explained, "here the images are supposed to impose themselves on you. The beauty of the colors, the meaning, the symbolism — it was very healing to me."

Icons of a sea angel, left, and a firefly by Angela Manno (Photo by Jim McDermott)

When it comes to how to talk about climate change, said Danielle Eubank, who has traveled the world painting images of the world's water sources, "we're always asking, 'Is it the carrot or the stick?' Do you show people how beautiful things are, or do you say, 'Hey look guys, we're bleeding?' "

Dresser agreed, saying, "People cannot imagine or engage with ecological disaster. It's too much information." The artist's challenge, she said, is to find that "tipping point" that gets the audience over that hump.

In one of her two paintings, a tiny bird's nest floats vertically upon a canvas that appears almost like water. It reminded me of the reed basket Moses' mother placed him in before she sent him down the Nile, hoping he would find a home before he drowned. Here, there is no chick in the nest, no sign of life. It seems another ominous sign of the doom upon us.

But Dresser was more drawn to the wonder of the nest itself. "This is from Wisconsin. These parents, they built this from horse hair. That's real horse hair." she explained. You could hear the admiration in her voice, one artist inspired by two others.

This piece is not about disaster, she said, "It's just a way to get people to focus on that little tiny miracle. That's all I want them to get."