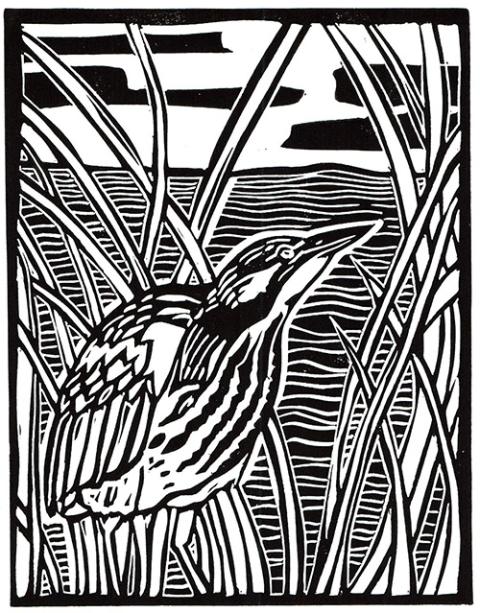

From left: "American Bittern," "Elegant Tern" and "Double-crested Cormorant" by Sarah Fuller, an artist in Los Angeles. Her work can be found at sarahfullerart.com.

Clack your beaks you cormorants and kittiwakes,

North on those rock-croppings finger-jutted into the rough Pacific surge;

You migratory terns and pipers who leave but the temporal clawtrack written on sandbars there of your presence ...

Seventy years ago this month, the poet William Everson first published in the Catholic Worker newspaper his classic "A Canticle to the Waterbirds," an electric account of faith, seabirds and spindrift surf along the western coast of the United States.

The artistic brilliance of poem and poet merit renewed attention. And so, too, does the canticle's anticipation of fundamental theological shifts in the understanding of faith and nature called for by Pope Francis. The cries of Everson's waterbirds point toward the "cry of the earth" articulated in "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," Francis' 2015 encyclical on faith and ecology.

Everson loved birds. In an essay on the Modern American Poetry Site, he recalled how as a boy growing up in California's Central Valley he "followed them through the fields with my heart in my throat, wonder-struck." The canticle itself arose from his encounter in the Oakland estuary with gulls who "lifted their wings in a gesture of pure felicity."

Advertisement

A recent convert to Catholicism in 1952, Everson considered religious life while living and working at a Catholic Worker House of Hospitality in West Oakland. Driven by recession, hundreds of migrant workers made their desperate way to the house for a meal and a bed and a few turns at a bottle. Not a wealthy person himself, Everson felt the faith-wearying weight of such poverty.

And then he saw the gulls. "Something sudden and conclusive broke bondage within me," he said in the essay, "On Writing 'A Canticle to the Waterbirds.' "

"My mind shot north up the long coast of deliverance, encompassing all the areas of my ancient quest, that ineluctable instinct for the divine ... where despite all man's meanness a presence remains unspoilable," he continued.

Double-Crested Cormorant, linocut print, ink and paper, 9x7 inches, 2022. By Sarah Fuller, an artist in Los Angeles. Her work can be found at sarahfullerart.com.

His composition of the canticle followed shortly and quickly after. He called the poem a "simple meditation of the mutual relation between birds and God and man" — a phrasing similar to Francis' tripartite conviction in Laudato Si' that the gospel of creation is constituted by "three fundamental and closely intertwined relationships: with God, with our neighbor and with the earth itself."

From its unmatched opening evocation of waterbirds and sea winds along the West Coast, the poem moves into a meditation on our creaturely debt to the divine and concludes with a call to a shoreline avian chorus to "send up the strict articulation of your throats / And say his Name."

Stanford literary critic Albert Gelpi called Everson the finest Christian English-language poet in the second half of the 20th century. (He said T.S. Eliot took the honor in the first half.) In Dark God of Eros: A William Everson Reader, Gelpi also noted that Everson stood in the American tradition of Walt Whitman in using "an expansive free verse line that could enfold and resolve self and nature into a verbal microcosm of the evolving cosmos." In terms of this rhetorical strategy in the canticle, mission accomplished.

Shortly before the publication of the canticle, Everson entered the Dominican order, took the name Brother Antoninus, and continued his remarkable poetry. (He later left the order and married Susanna Rickson.) In 1957, Time magazine dubbed him the "Beat Friar."

To be sure, the Dionysian drive in his work mirrored the passionate intensity of his ambient California world of Beat artists. Everson said of the canticle: "It is indeed in the Beat fashion — may even be the archetypal Beat poem, since it preceded Ginsberg's Howl by five years, but it is probably not violational enough to claim that honor."

Everson was a Catholic poet of eros and agape — of love ecstatically driven to possess and of love transformed for the sake of the other. In his recovery of eros as a dimension of a unified notion of Christian love, he anticipated Pope Benedict XVI's comment in Deus Caritas Est that a Catholic tendency to make eros and agape antithetical leads to a Christianity "detached from the vital relations fundamental to human existence, and [to] ... a world apart, admirable perhaps, but decisively cut off from the complex fabric of human life."

By contrast, Everson's eros-driven poetry charges out toward the world of waterbirds and more and thus also anticipates what Francis in Laudato Si' says should be at the heart of ecological conversion: "a loving awareness that we are not disconnected from the rest of creatures, but joined in a splendid universal communion."

Seeing things in the light of such energies in Everson's poetry allows us more readily to see the cosmic, sacramental logic behind Francis' admonition in Laudato Si' that the "ideal is not only to pass from the exterior to the interior to discover the action of God in the soul, but also to discover God in all things."

Elegant Tern, linocut print, ink and paper, 9x7 inches, 2022. By Sarah Fuller, an artist in Los Angeles. Her work can be found at sarahfullerart.com.

Seeing things in such an Eversonian light also points toward the divine presence amid the vast interlocking relations of creatures and systems in the world. As Francis puts it: "This leads us to think of the whole as open to God's transcendence, within which [the whole] develops."

We need to make this orthodox shift in our conception of God and nature. Within the Catholic community, we are stuck in a privatized faith oriented toward a transcendent God all but detached from the world. Such a faith is disposed to mistake the "vital relations fundamental to human existence" for a materialism antithetical to Christianity.

The late French philosopher Bruno Latour, in an essay on Laudato Si', laid out the consequences of such an erroneous conception of the divine now coursing especially through a so-called traditional Catholicism: "Hundreds of books written warning of the dangers of materialism, of immanence, of modernism, of technology, of science, or of the worship of matter; total indifference when it comes to corporate planetary destruction."

So we should return to Everson's waterbirds, who gesture, glint, hover, clack, venture into the remote ocean regions of sacred mystery and verify in their pure felicity the divine presence in our midst. Seventy years ago, Everson's magnificent "Canticle to the Waterbirds" imagined the world we actually inhabit: Where the cry of waterbirds singing God's praise is part of the chorus of the cry of the Earth.